By Rich Heidorn Jr.

President Trump’s March 26 executive order calling for actions to protect the grid from electromagnetic pulses (EMPs) has “troublesome” timing requirements, a Department of Homeland Security official told a NERC task force at its first public meeting Wednesday.

The task force was formed in response to the Electric Power Research Institute’s April report on EMPs, which concluded a high-altitude nuclear explosion could cause a multistate electric outage but not the nationwide, months-long blackout some observers have warned of. (See EPRI Report Downplays Worst-Case EMP Scenario.)

The task force, which met at NERC headquarters in D.C., was charged by the board of trustees to determine if any immediate mitigation should be taken and to identify additional research needs, said Vice President of Standards Howard Gugel. It is expected to make any recommendations for guidelines or other actions by the third quarter.

Using Physics to Bound Risk

Scott Backhaus, the Department of Homeland Security’s coordinator for electromagnetic pulse impacts on critical infrastructure, gave a briefing in which he described the “huge timing challenge” posed by the president’s executive order and talked about the need to revise the definition of critical infrastructure.

Backhaus urged the task force to “use physics and engineering to constrain our analysis” and avoid overestimating the risk.

“Let’s incorporate the engineered nature of the infrastructure systems. … Impacts may already be mitigated by existing control systems, redundancy backups, hardening that’s already in place … and existing restoration plans.”

“EMP is one of many threats, so we need to develop our best estimate of risk from EMPs and [geomagnetic disturbances] to place them in context of the other risks that the bulk system faces,” he continued. “In a world of constrained resources, if we overestimate one risk, that will suck all the air and all the money out of the room, and it could potentially degrade our ability to harden and respond to other risks.”

Seeking a Government Consensus

The Department of Energy (DOE), the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA), DOE’s nuclear weapons labs and DHS are working to develop a U.S. government consensus on intelligence- and science-based EMP threats that it can declassify and share with the industry, Backhaus said. “What’s the explosive package? How is it going to be delivered? How high can it be delivered? What’s the worst-case delivery?”

The analysis will be based on several EMP “waveforms,” to account for threats from multiple actors with a range of nuclear weapons technologies. “We need to address a sufficient number of different technologies [so] that we cover the span of our adversaries,” Backhaus explained. “We can estimate the impacts across the entire threat spectrum. We’re putting the decisions about how much risk you’re willing to take … to the people who spend money — the utilities.”

One task force member asked how different the current waveforms are from those developed in the 1950s based on the Soviet Union’s capability. “No comment,” Backhaus responded. “No comment,” he repeated as the questioner attempted a follow-up query.

Gugel asked Backhaus if NERC members will be able to obtain unclassified information on peak magnitudes or the duration of EMP events. “We’ve got to make sure we’re in the right ballfield,” Gugel said.

“How we remove the classified information is still a topic of discussion,” Backhaus said.

‘Huge Timing Challenge’

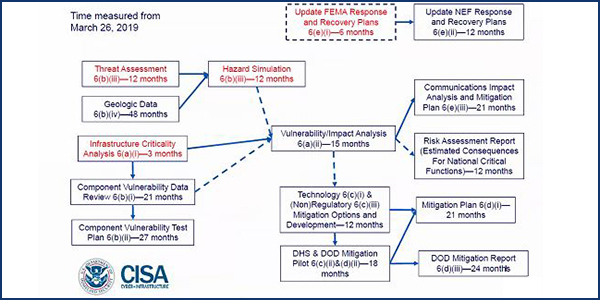

Backhaus noted the executive order calls for development of vulnerability impacts at the 15-month mark from March 26. “But for some reason, technology mitigation options and regulatory incentives come in month 12. So, we will not have finished any vulnerability or impacts by the time we have to suggest mitigation and regulatory incentives and non-regulatory incentives. There’s a huge timing challenge here.

“I need to give FEMA some guidance on the size of power outages that would be expected from an … EMP effect. Do they need to update their plans or are their plans sufficient to handle an outage of that size?” he continued. ” … FEMA needs to go and update its response recovery plans in month six. We still don’t even know what the impact is.”

“The timing wasn’t determined by DHS. It wasn’t determined by DOE,” Backhaus said.

Backhaus said DHS’s only option is to use existing impact studies that are sound and consistent with each sector’s best practices. DHS and DOE are currently peer-reviewing recent EMP impact studies from different entities, an effort to quell the “controversy” over the proper model to use.

Identifying Critical Infrastructure

Backhaus said DHS’s traditional criticality approach focuses on singular assets or tight clusters of assets, such as certain chemical plants and some banking and finance. “The threshold for calling them critical is when there’s a significant national or regional impact if one asset — or one cluster of assets — goes away.”

That, he said, is not appropriate for electric assets. Bulk power systems are highly redundant and “don’t really have singular assets. You can lose a large multi-gigawatt generator and … it impacts your operations, but you can operate through because you have redundancy both in the generation fleet and in the [transmission] network.”

The DHS approach also fails to recognize common-mode disruptions of components that are replicated throughout the networks.

“A lot of the work that [EPRI’s] done is on protective relays. Those would never be identified in this approach as a critical assets because the failure or any one of them is not that significant on the national or regional scale.”

He proposed adding to DHS’s criteria the identification of regional scale infrastructure networks whose disruption would create significant impacts. “So, things like ERCOT, … WECC, or [CAISO], however it makes sense to break those down,” he said.

He would also identify local distribution companies with common architecture that are replicated nationwide.

EPRI Study

EPRI’s Randy Horton briefed the task force on its April study, which recommended mitigation measures including shielding cables, enhanced grounding and modifications to substation control houses.

Horton acknowledged the study was limited to the grid and transformers and did not examine potential impacts on generation. “Trying to solve the EMP problem on the bulk power system is very much like trying to eat an elephant,” he said, noting the study’s call for additional research. “You’ve got to start somewhere, and the transmission system is a very important aspect of resiliency.”

Horton said the study found the impact of an E-3 pulse — a very low frequency pulse similar to severe geomagnetic disturbances (GMDs) although much shorter in duration — would be a voltage collapse in “a large region … on the order of the 2003 blackout, maybe a little bigger than that.”

EPRI is now conducting 18- to 24-month field trials of hardening measures at 17 U.S. utilities. Horton said the trials hope to prevent unintended consequences from the measures, such as protective system misoperations.

“There’s lots more work to be done,” he said. “We’re not finished by a long shot.”

Task Force Membership

The task force members, selected from names submitted by trade groups, include representatives from utilities Southern Co., American Electric Power, Dominion, Exelon, TVA and Xcel, along with the New York Power Authority, the NASA Goddard Space Center, FERC’s Office of Electric Reliability and the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association. The task force is not accepting additional members, said NERC’s Soo Jin Kim, to keep its numbers manageable.

It will hold a technical workshop on July 25 at NERC headquarters in Atlanta, she said.

Gugel said although the task force hasn’t been formalized with a reporting relationship to a standing committee, it will probably report to the Operating Committee, the Planning Committee or both. (See Standing-room Only for NERC EMP Meeting.)