By Rich Heidorn Jr.

An electric industry-funded report on high-altitude electromagnetic pulses (HEMPs) underestimated the risks the grid faces and should not be used as the basis for mitigation, according to a critique released this week by a little-known group with ties to Maxwell Air Force Base.

In April, the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) released a study that concluded a HEMP caused by a nuclear explosion could cause a multistate electric outage but not the nationwide, monthslong blackout some observers fear. (See EMP Task Force Looks at Black Start, Nukes.)

A group calling itself the Electromagnetic Defense Task Force (EDTF) said almost 200 of its members — “military, government, academic and private industry experts in various areas of electromagnetic defense” — produced a critique of the EPRI report and concluded that relying on it would not address “remaining vulnerabilities impacting large power transformers, generating equipment, communication systems, data systems and microgrids designed for emergency backup power.”

“If U.S. government policymakers rely upon the methodology and conclusions of the EPRI report, effective high-altitude EMP protections will not be implemented, jeopardizing security of the U.S. electric grid and other interdependent infrastructures,” the group said in its 20-page report.

Randy Horton, EPRI’s EMP project manager and one of the authors of the April report, defended the work Wednesday. “EPRI stands behind our EMP research results and welcomes technical debates that are supported by science, facts and data,” he said in a statement. “Our conclusions were reached after three years of extensive laboratory testing and analysis of potential EMP impacts on the electric transmission system.”

An EPRI spokesman declined to elaborate or respond to specific criticisms, saying, “I think Randy’s quote lays out a good basis for further discussion.”

FERC declined to comment, and NERC and the Edison Electric Institute did not respond to requests for comment. Scott Backhaus, the Department of Homeland Security’s coordinator for EMP impacts on critical infrastructure, told ERO Insider on Thursday he is working on a response but that it is not complete.

EPRI’s report called for mitigation to protect the grid from the impacts of E-1 pulses — the first “hazard field” caused by an EMP, which lasts for about 2.5 nanoseconds. The second impact, an E2 EMP, lasts up to 10 milliseconds. The last hazard field, an E3, is marked by a very low frequency pulse that can last for hundreds of seconds. The event would be like a severe — albeit much shorter — geomagnetic disturbance (GMD) caused by solar flares.

EPRI acknowledged that its research was limited and did not include generation and distribution, saying it intended additional research on those subjects.

Scenario Choices

But the task force said EPRI also erred by not using realistic, worst-case scenarios in its analysis.

“Despite having access to defense-conservative Department of Defense threat scenarios, EPRI used alternative Department of Energy scenarios that assume adversaries would detonate nuclear weapons at nonoptimal altitudes, when the optimal altitudes are available in the open literature,” the report says.

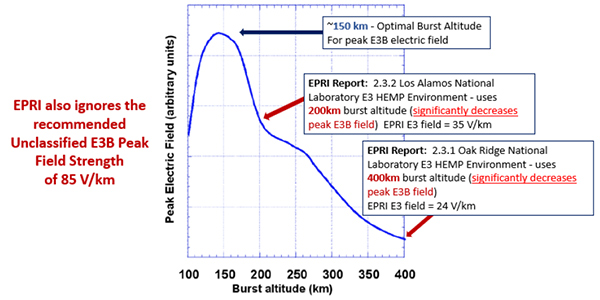

The task force said a burst height of 75 km would produce the strongest E1 field strengths, but that EPRI used a height of 200 km, lowering the peak E1 field strength by almost two-thirds. Similarly, EPRI did not use the 150-km optimal burst height for peak E3 field strengths, choosing instead a height of 400 km.

“The methodology and findings of the EPRI report are not only markedly dissimilar from previous EMP studies, but in many cases entirely opposed to more than 60 years of prior DOD, government and contractor research and findings on EMP, system effects and hardening,” it said.

Russian and Chinese scientists have published research that calculated E1 impacts at least twice as great as those used in EPRI’s study, it said. “By avoiding the use of data from declassified Soviet EMP tests on the realistic E3 threat level, EPRI was able to minimize numerical estimates of damaged grid equipment, including hard-to-replace high-voltage transformers.”

“EPRI also assumed latitudes and longitudes for its detonation scenarios that are nonoptimal for producing maximum HEMP fields in the Northern Hemisphere,” EDTF said. EPRI assumed the detonation would be over the center of the U.S., not on the most populated portions of the country or the areas with most of the electric generation, the critique said.

Optimistic ‘in the Extreme’

The report says the digital protective relays (DPRs) on which EPRI focused its E1 research are more resilient than other grid elements such as substation communications and that EPRI suggested the relays would have a higher survival rate than previous peer-reviewed studies have found.

EPRI’s assessment of E1 HEMP impacts on voltage stability found that about 21,500 line terminals would be affected. Of the affected relays, EPRI assumed 1% of them would cause simultaneous tripping, which it said would cause the system to experience “perturbation” but “remain stable.”

“The EPRI report does not explain EPRI’s methodology of choosing just 1% of these relays, nor does it explain how EPRI can assume that the entire system will ‘remain stable’ when these relays are randomly tripped,” EDTF said.

EPRI did not assess how the failure of DPRs to prevent bus and transformer overloads or protect against over- and under-frequency and over- and under-voltage conditions would affect the grid, EDTF said.

EPRI also assumed that attackers would deploy only a single nuclear weapon in a HEMP attack, ignoring the risk of multiple HEMPS, according to EDTF.

“Protective relay damage and associated line terminal loss from realistic HEMP scenarios could be far greater, especially with a multiple-bomb EMP attack. Relay malfunction during a HEMP attack would likely cause other electric grid systems to fail, resulting in large-scale cascading blackouts and widespread equipment damage. Notably, E1 effects on protective relays are likely to interrupt substation self-protection processes needed to interrupt E3 current flow through transformers,” EDTF said.

“An initial HEMP attack could render a number of relays inoperable, causing grid debilitation due to the loss of transformer isolation, fault protection, and islanding capabilities. Thus, a follow-on HEMP attack on a grid with a portion of damaged or disrupted DPRs would likely cause increased and catastrophic equipment damage from flashovers, uninterrupted overloads, faults and cascading events resulting in a wider-scale and longer-duration blackout. Also, a second HEMP attack after damaged DPRs are replaced could eliminate the ability to recover due to depletion of DPR spare inventories.”

The EDTF noted that “large-scale grid blackouts have occurred in the past from single-point failures, such as the Northeast Blackout of 2003, which was caused by overgrown trees contacting electric transmission lines.”

The blackout affected more than 70,000 MW of load, leaving 50 million people without electricity. “In contrast, EPRI’s report concludes that a HEMP attack on the same Eastern Interconnection would cause limited regional voltage collapses and affect roughly 40% of the electrical load lost in the 2003 blackout. Experience with cascading collapse in the Eastern Interconnection shows EPRI’s finding to be optimistic in the extreme.”

Authors’ Identity Shielded

EDTF said its critique was the work of attendees of the group’s second “summit” in May under “Chatham House Rules,” in which they contributed without attribution. “The experts who contributed to this specific document range from uniformed military personnel, to civil servants throughout a range of government agencies and various national laboratories, to internationally renowned and published engineers.”

The critique was circulated by the Foundation for Resilient Societies and published on the website of Over the Horizon, which describes itself as “a digital journal that brings together disparate perspectives to advance the conversation on the emerging security environment.”

Resilient Societies President Thomas S. Popik, a former Air Force captain who attended the EDTF summit, said in an interview that the critique “has a firm scientific basis.”

The EDTF published the names of more than 100 organizations it said were represented at the summit, including DHS, FERC, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, NASA and several units of the Air Force. The only individual named in the critique is Air Force Maj. David Stuckenberg, who did not respond to requests for comment.

The Air Force also did not respond to questions about its relationship with the EDTF. The task force has a webpage on the Maxwell Air Force Base website, and its 2018 report is published on the website of the base’s Air University and included in the Homeland Security Digital Library. The 2018 report lists as authors Stuckenberg, former Navy Secretary and CIA Director R. James Woolsey Jr., and Air Force Col. Douglas DeMaio, who gave a presentation to the NERC EMP Task Force in July. (See Air Force: US Must Take ‘Higher Ground’ in Space.)

Popik said he wasn’t certain if Resilient Societies is part of the EDTF. “I know that we were invited to the meeting, so that would imply we’re part of the task force, but the actual conditions for membership in the task force are… I think it would be best if you ask that question of Maj. Stuckenberg.”

Incentives and Motives

EDTF said it “operates on the military’s premise of planning for the reasonable upper-bound scenarios and validating results through real-world testing.” EDTF said EPRI’s report might dissuade transmission owners and operators from mitigating EMP risks or planning for post-HEMP grid restoration. “Some EDTF personnel working on HEMP-mitigation efforts alongside electric industry partners have lost both momentum and the interest of their industry partners,” it said.

Popik praised NERC for including him as the only non-industry member of its EMP Task Force. “That’s been an open and transparent process, which is coming to a solid proposal for a process to address the executive order,” he said. “It really is very important to distinguish the work of the EMP Task Force at NERC from the efforts of the Department of Homeland Security and EPRI and [the] Department of Energy in regard to this study of EMP effects.”

He cited DHS’ Backhaus, who told the NERC task force in June that they should “use physics and engineering to constrain our analysis” and avoid overestimating the risk. “EMP is one of many threats, so we need to develop our best estimate of risk from EMPs and GMDs to place them in context of the other risks that the bulk system faces,” Backhaus said. (See EMP Task Force Takes ‘First Bite of the Elephant’.)

Popik said utilities “without a ready means for cost recovery [and] faced with the potential of a very expensive grid security standard … would have ample incentive to make sure the EMP threat was not — you can put this in quotes — ‘overestimated.’”

“… When you try and use the so-called best available science and physics and engineering to … avoid a conclusion that would be in conflict with a regulatory agenda, that’s not good science.”