By Holden Mann

“Significant and rapid change” will cause short-term challenges with resource adequacy in some regions, but utilities should be able to turn the evolving resource mix to their advantage with appropriate planning, NERC said last week.

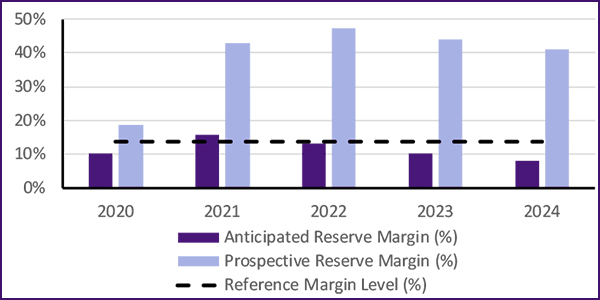

NERC’s 2019 Long-Term Reliability Assessment reported that most regional entities had sufficient resource capacity to meet projected demand over the next 10 years. The two exceptions were ERCOT and Northeast Power Coordinating Council-Ontario, both of which were assessed as “marginal” because of anticipated shortfalls in generating capacity in the next five years.

In the case of ERCOT, the deficiency — about 4,900 MW by 2024 — is largely a result of the canceling of several planned wind, natural gas and compressed air energy storage projects, totaling about 3,900 MW, along with last year’s retirement of the 470-MW Gibbons Creek coal-fired plant. NERC also revised its summer peak demand forecast in the region upward by about 1,300 MW per year from 2019 through 2023, widening the gap further.

Serious disparities between demand and capacity “could lead to an increased risk of entering emergency operating conditions” such as rotating outages during peak hours, NERC said. However, the organization noted that ERCOT has a large amount of Tier 2 resources — planned capacity that has completed a feasibility, facilities or system impact study, has requested an interconnection service agreement, or is included in an integrated resource plan — under development. These resources are projected to come online after 2023 and should be more than adequate to satisfy demand.

For NPCC-Ontario, the shortfall of about 600 MW is primarily because NPCC’s nuclear retirement and refurbishment program, which introduces the risk that planned upgrades may not be completed on schedule, leaving generating resources offline during periods of high demand. Here, the short-term deficiency is expected to be addressed by new market mechanisms to be introduced by Ontario’s Independent Electricity System Operator in the next few years that will allow additional resources such as off-contract generators and storage facilities to participate in auctions.

Wind, Solar, Gas Drive Resource Mix Changes

While long-term generating capacity is sound, the report did note that North American utilities will need to update their internal infrastructure to handle the developing resource mix.

More than 330 GW of installed capacity from wind and solar are planned to be added through 2029, growing their collective share of the grid to 26% from their current level of 15%, while nuclear and coal together decline from 29% to 23%. Natural gas is projected to decline as well, but at 36% in 2029, it will still hold the largest share of generating capacity.

This shift away from conventional synchronous generating resources will introduce new challenges, such as meeting demand shifts with intermittent renewables. NERC recommended that operators install additional system ramping capability to offset the variability of the sun and wind, along with upgrading their ability to forecast supply disruptions. Investment in transmission infrastructure is also needed in order to keep up with the spread of small-scale renewable energy projects, many of them in remote locations.

The report urged utilities to prepare for disruptions to the natural gas transportation system, such as line breaks and well freeze-offs, as well as identify how events in the electrical system itself — for instance, power failures to electric-powered compressors — might impact pipelines.

DERs and Storage Require New Thinking

Distributed energy resources, such as roof-mounted solar panels, will also play a growing role in the grid over the next 10 years, growing from 20 GW currently to more than 45 GW by 2029, accompanied by an expansion in grid-connected electric storage from less than 1 GW to nearly 9 GW (counting projects at all stages of construction). (See DOE’s Walker Sees Big Cuts in Storage Costs.) These projects have the potential to help maintain grid reliability and stability through decentralizing generation and locating it closer to demand. But utilities don’t always have visibility or control over the DERs, and their effects are “not fully represented in [bulk power system] models and operating tools,” NERC said.

“In areas with large or emerging DER penetrations, current operational models and system studies do not properly account for DERs. These models and studies will need to be improved to accurately represent the system’s behavior.”

The LTRA predicts utility-scale storage will grow from 708 MW as of 2017 to more than 8.5 GW by 2024.

“Before this storage is built and integrated into the BPS, the ERO should identify, assess and report on the risks and potential mitigation approaches to accommodate large amounts of energy storage on BPS reliability,” NERC said.