Experts at ReliabilityFirst’s Insider Threats Webinar on Wednesday warned that many common insider threat mitigation strategies can actually increase the risk of attacks and urged utilities to take a different approach to internal security.

“When we typically think about security controls, we’re talking about disabling somebody’s access or … doing something else punitive to them,” said Dan Costa, technical manager of enterprise threat and vulnerability at Carnegie Mellon Software Engineering Institute. “[But] the likelihood of that insider [causing] some harm against the organization might be best mitigated by … retraining, rebalancing somebody’s workload, [or] having coworker conflict training and mediation sessions available. … Organizations where employees are happy about working there … tend to experience less insider events than those that do.”

Insider threats — defined by Costa as the “potential misuse of authorized access to an organization’s critical assets … in a way that has the likelihood to have some negative outcome” for the organization — are a unique hazard for any company, in that by definition, they originate from those in whom the entity has already placed a great deal of trust. As a result, these incidents are potentially more damaging than external attacks and more likely to be overlooked by management.

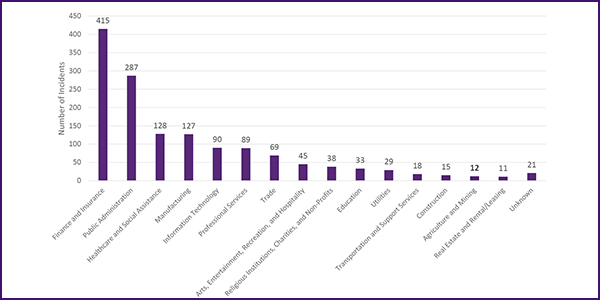

They are also frequently overlooked by outsiders: As Costa noted, many organizations prefer to handle insider threat events internally, which means that without legally mandated reporting, the number of attacks reported in publicly available statistics may be deceptively low. Carnegie Mellon’s own statistics, which are based on court records, show a far higher incidence of insider threat events since 1996 in the finance and insurance industry, which has relatively strong fraud prevention laws, than in the utility sector.

Even if Carnegie Mellon’s record of 29 insider incidents in the utility sector over 24 years is taken at face value, they must still be viewed seriously, given the fact that more than a third of these attacks led to financial impacts in the six figures.

“Insiders … know what is valuable to your organization; they know what is mission-essential to your organization,” Costa said. “They know how it’s protected; they know how to bypass or circumvent those protections; and insiders that are sufficiently motivated to intentionally cause harm to the organization are uniquely positioned to do so.”

Looking for Warning Signs

The vulnerability doesn’t end with current employees, as illustrated in the attack suffered by instrumentation developer Omega Engineering at the hands of former network administrator Timothy Lloyd. Steven McElwee, chief information security officer at PJM, described how Lloyd struck back at his former employer in 1996 when he was demoted, then fired.

“Because of his privileged access as a network engineer, and because of some temper issues, he didn’t handle it very well,” McElwee said. “So he wrote six lines of code … very simple, very elegant, and it was a time bomb. When he was fired, and he left the organization, it successfully deleted all of the source code for Omega engineering. It was a devastating blow to the company, and I don’t think they ever really recovered from it.”

Omega later reported spending nearly $2 million repairing the damage from Lloyd’s attack and losing almost $10 million in revenue, resulting in 80 layoffs. Quoting a line from the film “Batman Begins,” (“It’s not who I am underneath, but what I do that defines me.”) McElwee listed several behaviors that should have tipped managers off that Lloyd was likely to cause issues and led them to take additional precautions.

“First of all, he was demoted. That was a sign. … He was on someone’s radar as a problem employee,” McElwee said. “Second, he was considered to be a hothead. So, they might have expected a strong reaction when they were firing him and been able to take some additional precautions. Third, someone knew he was going to be fired. All of these factors should have raised lots of red flags.”

Support, not Punishment

Given cautionary tales like Omega’s, organizations might feel the best defense is to cut off insider attacks before they begin by locking down potentially difficult employees’ access to critical assets as soon as problems emerge, or by transferring, demoting or even terminating these workers. But participants in the webinar warned that these tactics are likely to backfire, creating the very situation they are intended to prevent.

Presenting Carnegie Mellon’s models for the incitement of insider fraud and sabotage events — the two most prominent types of incidents in its research — Costa observed that the vast majority of insider attacks have multiple contributing factors.

In the case of fraud, an individual may begin with no malicious intent toward their employer but move over time toward a decision to steal from the workplace because of family issues, financial pressures, resentment toward the company and other issues. Sabotage may stem from feeling underappreciated and mistreated by coworkers and management.

Both situations can be aggravated by punitive measures such as reassignment, demotion or firing. An employee considering theft of company property may feel that such steps leave them with no legitimate option for solving their issues, while one thinking of sabotaging the workplace may feel insulted by attempts to remove their access and move forward with their plans.

“It’s this combination of concerning behavior and then maladaptive organizational responses, [and] these cycles that start to happen between more concerning behaviors exhibited and more maladaptive organizational responses,” Costa said. “There’s a tipping point where eventually the insider becomes motivated to cause harm to the organization.”

This does not mean that organizations should overlook warning signs for fear of pushing employees into a downward spiral, or that there are no situations where removing an insider’s access is appropriate. However, speakers emphasized that the most effective way to reduce the amount and impact of insider attacks is to understand the pressures that lead employees to cross the line and address them where possible.

“Everyone has vulnerabilities … and not all kinds of vulnerabilities are going to cause issues in their organization,” said Benjamin Gibson, a senior physical security analyst at the Electricity Information Sharing and Analysis Center. “It’s some of these confluences of factors … where you start raising the red flag. … Part of the program is to identify where the vulnerabilities are, know where the people might have vulnerabilities, and knowing can help mitigate [them].”