Electric distribution systems that carry energy to end consumers are highly vulnerable targets for cyberattacks, but these risks are “not fully” addressed by the Department of Energy’s cybersecurity strategy, according to a new report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

GAO’s “Electric Grid Cybersecurity” report draws on interviews with officials from DOE, FERC, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the Department of Homeland Security, along with nine national laboratories with expertise in grid distribution systems’ cybersecurity. The agency also solicited information from nonfederal entities, such as state public utility commissions, distribution utilities, grid equipment manufacturers, cybersecurity firms, electric industry associations and electric industry associations.

The report expands on a previous document released in September 2019. In that publication, the agency advised DOE to “develop a plan aimed at implementing the federal cybersecurity strategy for the grid [that includes] a full assessment of cybersecurity risks to the grid.” GAO also recommended that FERC consider revising NERC’s critical infrastructure protection (CIP) reliability standards to align with the NIST Cybersecurity Framework, while evaluating the “risk of a coordinated cyberattack on geographically distributed targets” for future updates to reliability standards.

DOE and FERC both pledged to follow the 2019 report’s suggestions, and the follow-up report notes that DOE’s “plans and assessments address some elements of risks that enable cyberattacks on the grid’s distribution systems.” For example, GAO cites DOE’s planned expansion of the Cyber Risk Information Sharing Program to include cyber threat indicators for operational technology (OT) networks as well as information technology (IT) networks.

FERC also initiated an inquiry last year into possible gaps in the CIP standards, with questions explicitly derived from the NIST framework (RM20-12). (See FERC Starts Inquiry on CIP Standards.)

DOE’s Work Far from Complete

However, GAO warned that DOE’s efforts are only a small part of the work required in order to address the threat to distribution systems. Moreover, none of the federal and nonfederal entities consulted for the report were aware of plans to even study the impact of such a threat, much less mitigate it.

“DOE officials told us that they are not addressing risks to grid distribution systems to a greater extent in their updated plans because they have prioritized addressing risks facing the bulk power system,” GAO said, under a definition of “bulk power system” that includes only generation and transmission assets. “Officials said a cyberattack on the bulk power system would likely affect large groups of people very quickly, and the impact of a cyberattack on distribution systems would likely be less significant.”

This viewpoint is dangerously shortsighted, GAO warns, noting that while “none of the cybersecurity incidents reported in the [U.S.] have disrupted the reliability … of the grid’s distribution systems,” there are examples of successful distribution-focused attacks on foreign power grids. Most notably, the 2015 blackout in Ukraine — for which the Justice Department indicted six Russian military intelligence officers in October 2020 — involved attacks on the computer systems of three Ukrainian energy distribution companies. (See Six Russians Charged for Ukraine Cyberattacks.)

In addition, even an attack that cuts power to a limited area could have major consequences depending on where the outage occurs. A power outage in a major city, for example, might disrupt a wide range of businesses with a national or even global reach, or result in cascading outages for a larger region.

Compounding these dangers is the growing number of “networked consumer devices that are connected to the grid’s distribution systems … [that] can demand a high amount of electricity from the grid” but offer “limited visibility and influence to distribution utilities” because their internet access is controlled by consumers. Examples of these devices include electric vehicles and their charging stations, as well as smart inverters for household solar panels.

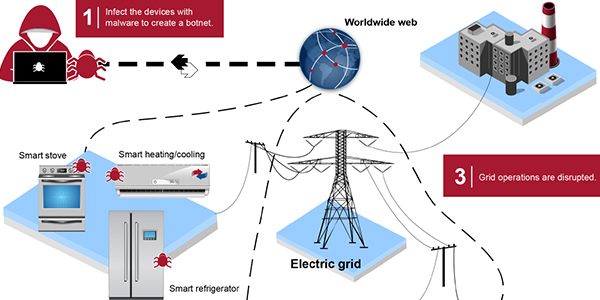

Locating such devices behind customer networking equipment is risky in large part because these users, particularly residential customers, are almost certainly not trained in cybersecurity and unaware of the tools and strategies available to skilled hackers. One potential attack route noted in GAO’s previous report is the use of compromised devices to create a botnet — a network of devices infected with malicious software and controlled as a group without the owners’ knowledge. With control over a large enough botnet an attacker could create widespread power disruptions simply by turning the devices on and off at the same time.

Rooftop solar panels themselves, along with other distributed energy resources such as battery storage units that are connected directly to the distribution system, make up another rapidly growing list of potential points of entry for malicious hackers. Even if these facilities’ internet access is controlled by utilities rather than consumers, the large number of installations means many more weak points for attackers to exploit, especially in devices made by the same manufacturer where common vulnerabilities may be known.

No Unified Cyber Approach

National laboratory officials told GAO that a growing range of actors is capable of carrying out cyberattacks on distribution systems, including nations, criminal groups, terrorists, individual hackers looking for a challenge or to send a political message, or insiders. But while states and utilities are working to improve cybersecurity on the distribution systems, their measures are “not uniform across jurisdictions” or subject to nationwide oversight.

All six state PUCs interviewed for the report said they “have incorporated cybersecurity into their routine oversight responsibilities,” albeit without mandatory standards for grid distribution systems. The application of cybersecurity varies across commissions: three have periodic discussions on the topic with utilities; one incorporates cybersecurity into its regular management audit of utilities; another uses “broad regulatory authority to review utilities’ response to incidents;” and the last said its state’s legislature had given it authority to “ensure that utilities … employ cybersecurity best practices,” without specifying how this is done.

Only three PUCs had hired staff members to focus on cybersecurity responsibilities. Of the others, two told GAO they did not have the resources to hire dedicated personnel, while the other said it relies on utilities to monitor their own cybersecurity processes.

While distribution utilities have no mandatory standards to follow with regard to cybersecurity, all of the utilities surveyed in the report said they had incorporated the issue into their internal practices in various ways. A common approach is to use DOE’s Cybersecurity Capability Maturity Model “to assess their cybersecurity posture and manage cybersecurity risks.” Some utilities also use tools from other sources such as the American Public Power Association (APPA), the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association (NRECA), NIST and DHS.

Federal agencies have provided support for these efforts in the form of training and exercises such as the GridEx security exercise, threat information, assessment tools and research and development. However, because these continue to be developed without a specific high-level focus on distribution systems from DOE, GAO warned that “federal support intended to … improve distribution systems’ cybersecurity will likely not be effectively prioritized.”

In a response attached to the final report, DOE said it “appreciates” the recommendations from GAO and promised to “continue to focus on mitigation of cybersecurity risks and evaluate the most critical risks to the energy sector.” The department noted the work of the Office of Cybersecurity, Energy Security, and Emergency Response to address cybersecurity across the grid, including in the distribution system.

In addition, DOE highlighted two ongoing research programs focused on distribution cybersecurity conducted since 2016 in partnership with NRECA and APPA and “reinvigorated” last year, that are intended to be completed by September 2023.