One in four major U.S. energy companies — including 17% of the largest electric utilities — are “highly susceptible to a ransomware attack,” according to a report issued this week by cybersecurity firm Black Kite.

The 2021 Ransomware Risk Pulse: Energy Sector report presents the results of Black Kite’s survey of the 150 largest energy companies by market cap in the U.S.; included in the report are 29 electric utilities and 58 and 63 companies in the oil and gas industries, respectively. Black Kite assigned a rating to each company based on its proprietary ransomware susceptibility index (RSI), a number between 0 and 1 broadly determining how susceptible the company and its third parties are to an attack.

RSI ratings are based on a combination of publicly available information and data gathered on the dark web. Factors that can damage a company’s score include leaked credentials, use of older software versions with unpatched vulnerabilities, open remote desktop protocol ports and misconfigured email systems.

Ransomware-specific assessments are relatively new for Black Kite, which started offering the service earlier this year in response to concerns from clients about their own vulnerability to ransomware, and that of their vendors and suppliers even more so. Bob Maley, Black Kite’s chief security officer, told ERO Insider that ratings systems that give overall cybersecurity grades may not take into account vulnerabilities to specific risks.

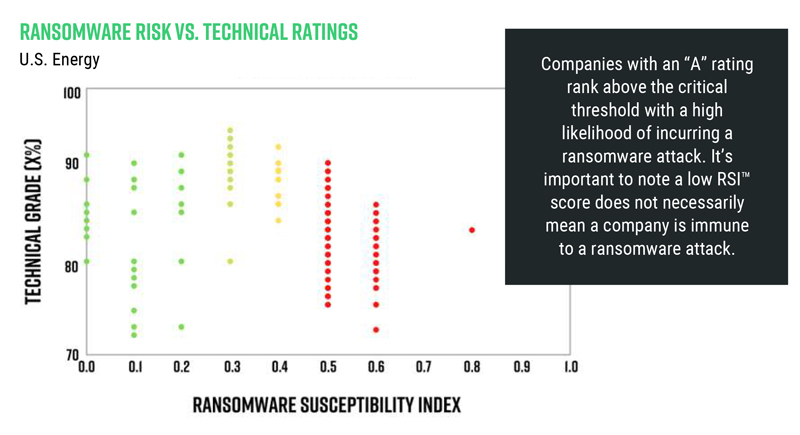

“Grades are a good overall view of cyber hygiene, but they don’t always indicate where the highest risk is,” Maley said. “And what we’ve discovered through this process is that … some companies that have very good cyber hygiene [but] are highly susceptible to ransomware.”

Major Vulnerabilities Evident Across Sector

Black Kite found that 25% of all the companies surveyed had an RSI of 0.6 or more, which the company considers critical. An RSI of 0.4 to 0.59 is considered average, and a low RSI is 0.39 or below.

The electricity industry fared relatively well compared to the natural gas and oil industries, with 17% of surveyed electric utilities returning a critical RSI compared to 28% of oil companies and 25% of natural gas companies. Companies with a low RSI did not make up the majority of any industry, though oil came closest with about 24 of 58 companies, compared to 11 of 29 electric utilities and 16 of 63 gas companies.

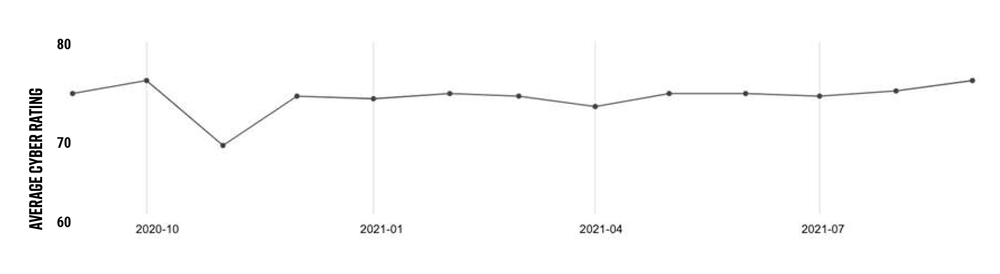

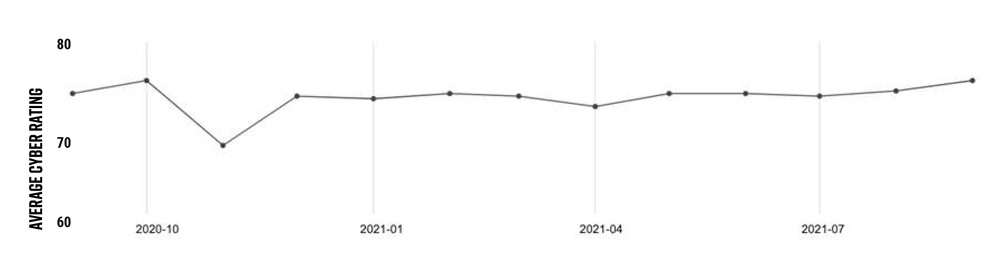

The RSI ratings stand out in contrast with the “relatively decent cyber posture” of the energy industry, with Black Kite’s overall average cyber hygiene rating of companies mostly hovering around 75% for the last 12 months. Many of the companies with high RSIs demonstrated technical grades of 80% or above, while some of the companies with the lowest RSIs also had the lowest technical grades, apparently confirming Black Kite’s assertion that ransomware vulnerability is not necessarily correlated with overall cyber proficiency.

Examining specific vulnerabilities provides a better indication of the sector’s areas for improvement. Credential access is a particular concern: Black Kite found at least one leaked credential within the last 90 days from 77% of U.S. energy companies, an especially sensitive area given that the ransomware attack on Colonial Pipeline this May — which led the company to shut down its entire network — originated with a leaked password for the company’s virtual private network.

Email security is also an area of high vulnerability; despite the fact that email is the “most common channel leveraged during ransomware deployment,” Black Kite found that 74% of U.S. energy companies still have not properly configured their email services to prevent email spoofing. This means that attackers can easily pose as employees’ coworkers or managers to trick them into exposing sensitive information they would not normally provide to outsiders.

U.S. regulators responded to the Colonial hack and other recent ransomware attacks with heightened cybersecurity requirements, which Maley acknowledged could help improve the sector’s baseline for cyber hygiene. (See TSA Issues New Pipeline Cybersecurity Requirements.) But he warned that given the fluid nature of the cyber threat landscape and the inevitable delays in implementation of new standards, attempts to regulate the sector into safety are ultimately a losing proposition.

“From a high level view, [those things] make a lot of sense. But when I take off the regulatory glasses and put on the bad actor glasses, [they] don’t concern me at all,” Maley said. “The way bad actors work is, they will try something, and as long as it’s working … they will continue to do it. They’ll continue to profit off that. But when it stops — they’re very smart, [and] they’ll find other avenues.

“I think it’s more about how do leaders of companies get that mentality of … ‘how are the bad actors going to get into us today?’” he continued. “Not what checklists they’ve done or which auditor certification they’ve acquired. … And it is a daily basis because it can change very quickly.”