With the U.S. Department of Defense increasingly reliant on civilian electric infrastructure, state utility regulators must be prepared to work with utilities and the military to safeguard national security, according to a new report from the National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners (NARUC).

The Regulatory Considerations for Utility Investments in Defense Energy Resilience report, published last week, was prompted by the transformations over the past few decades in both the mission of the U.S. military and in its relationship to the national power grid. Whereas the military previously did its job largely outside the continental United States, the power of digital communications has allowed more and more missions to be conducted from within the nation’s borders — most visibly through the use of remotely controlled drones for intelligence and combat, but also with cybersecurity and signals intelligence.

Shifting these tasks to the continental U.S. meant the electricity needs of domestic military bases kept increasing, and the pre-World War II model of facilities managing their own power needs could not keep up with demand. Fortunately for DOD, by this point the civilian power grid had grown capable enough that bases could tap into commercial utilities.

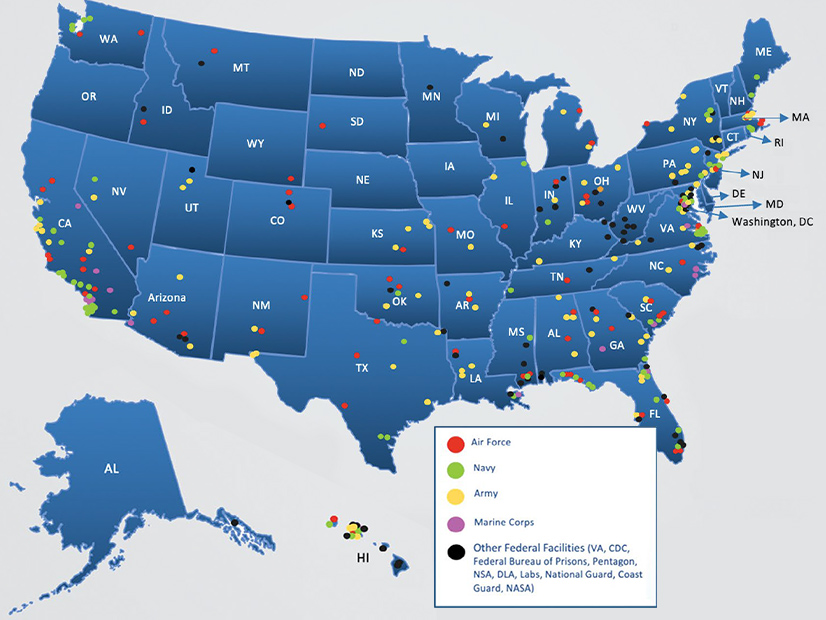

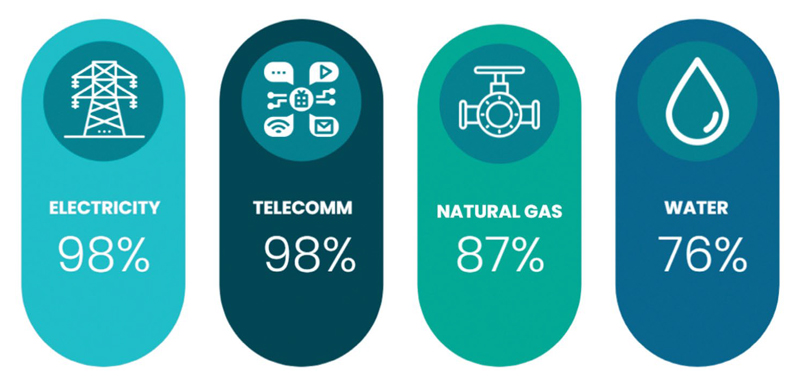

Similar trends were underway regarding other utilities. According to figures from the Government Accountability Office (GAO), today more than 98% of military facilities rely on the civilian power grid, 98% depend on commercial telecom providers, 87% on the commercial natural gas system and 76% on community water. More than 300 major military and national security installations are served by investor-owned electric utilities, according to Edison Electric Institute, with additional bases served by rural coops and municipal utilities.

Bases No Longer Isolated from Outages

But the integration with the national grid and the end of electric self-sufficiency comes at a price of increased vulnerability to outages. NARUC observed that in fiscal year 2019, DOD “experienced 2,572 unplanned utility outages, of which 542 lasted eight hours or longer, including at installations with missions that cannot tolerate interruptions.”

Percentage of Defense Department installation reliance on community infrastructure, as calculated by the U.S. Government Accountability Office. | NARUC

Percentage of Defense Department installation reliance on community infrastructure, as calculated by the U.S. Government Accountability Office. | NARUCConcerning electric outages specifically, the report singled out major events such as hurricanes Irma and Maria in 2017 and Hurricane Michael in 2018, all of which “severely impacted nearby DOD installations and operations” in Florida and the Caribbean. In addition, Superstorm Sandy in 2012 demonstrated a different kind of vulnerability, when response efforts by the National Guard and other military units were crippled by power outages at their bases.

Military installations are also vulnerable to outages from cyberattacks against commercial utilities; such attacks may not be specifically aimed at disrupting defense operations, or in the case of nation-state actors like Russia and China, may be intended as an indirect threat against a rival’s military. Additional dangers come from infrastructure interdependencies; disruptions in the natural gas system can cause failures in the electric grid, as occurred during February’s winter storms in Texas and the Midwest.

The military’s reliance on power from commercial utilities puts pressure on those utilities’ regulators. Not only do they need to work on behalf of ratepayers in their states, but they also must be mindful that their decisions do not jeopardize the security of the U.S.

Within DOD, the Office of the Secretary of Defense handles overall energy policy regarding military installations, but the department has “multiple levels of energy governance and responsibility,” according to NARUC. These include personnel within each branch of the military and staff at the installations themselves that may work with regulators. The report advises regulators to “be mindful of the level of DOD bureaucracy with which they are interacting” and the type of influence that each level holds.

Role of Regulators Still Undefined

Overall, the report acknowledged that the role of state utility commissions in supporting the resilience of military installations “remains nascent,” and predicted that regulators will need to “proactively engage with issues related to defense energy resilience, or … increasingly see issues related to defense energy resilience integrated into their normal course of business.”

Questions that regulators may have to address include who pays for investments related to defense energy resilience: Should it come exclusively from the DOD or other federal programs, or should ratepayers foot part of the bill, since uninterrupted national security operations is an obvious public good? How might regulators calculate the benefits of the needed investments in order to sell them to a skeptical public? Should ratepayers support investments in cybersecurity intended to benefit the military, if such investments benefit the greater public as well?

These questions may be overwhelming for regulators who are still grappling with the idea that their decisions impact the nation’s military readiness, and the report noted that some commissions may wish to wait and see how existing government programs develop before stepping into the debate. But regulators may also want to “proactively define the practices and processes” for utilities’ collaborations with the military.

NARUC provided some steps that regulators could take to engage with the topic of defense energy resilience. First, commissions may identify military installations in their state that might rely on regulated utilities, and work with DOD representatives to identify energy resilience projects with which the commission might need to engage.

Regulators can also work with the military on joint energy resilience metrics, value of resilience investigations, and investigate defense energy-related cybersecurity investments. Finally, secure communications frameworks should be established so that sensitive materials can be discussed without fear of malicious eavesdroppers.