The growing frequency of severe weather events and a rapidly diversifying resource mix will present closely intertwined challenges to electric reliability in the coming decade, NERC said in its annual Long-Term Reliability Assessment (LTRA), released Friday.

“Our traditional baseload generation plants like coal and nuclear are retiring, and lots of new natural gas and variable generation, mostly solar and wind, have been deployed,” John Moura, NERC’s director of reliability assessment and performance analysis, said at a media event accompanying the release of the report.

Moura called the transition to renewable resources “a really great thing for our decarbonization efforts,” but added that “it’s vitally important that we [build and operate] a bulk power system that can be resilient to the extreme weather we’re seeing.”

NERC produces the LTRA every year to assess North American resource adequacy in the next decade and to identify trends that could affect grid reliability and security. This year’s assessment identified resource adequacy as a serious concern in MISO, Ontario and the south-central U.S., while extreme weather poses the biggest concern in New England and Texas. The Western Interconnection — including California, the Northwest and the Southwest — faces both risks.

Transition to Renewables Continues

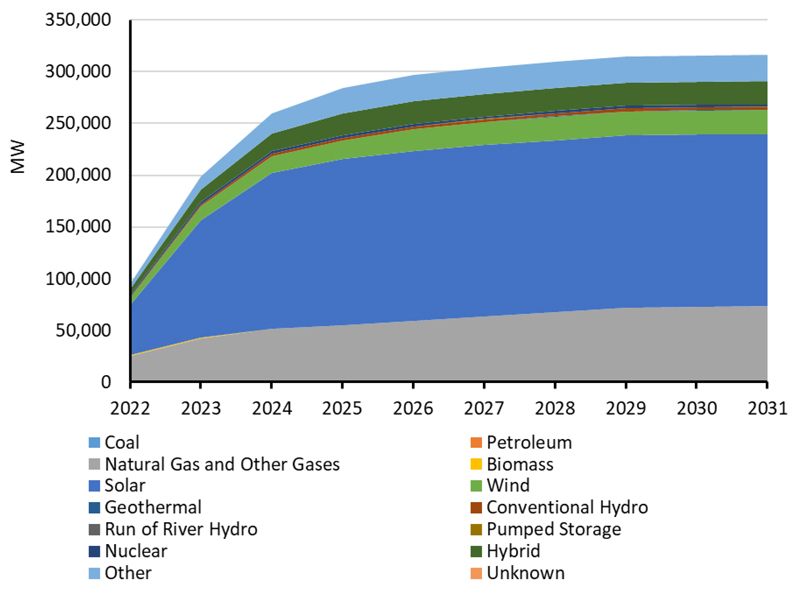

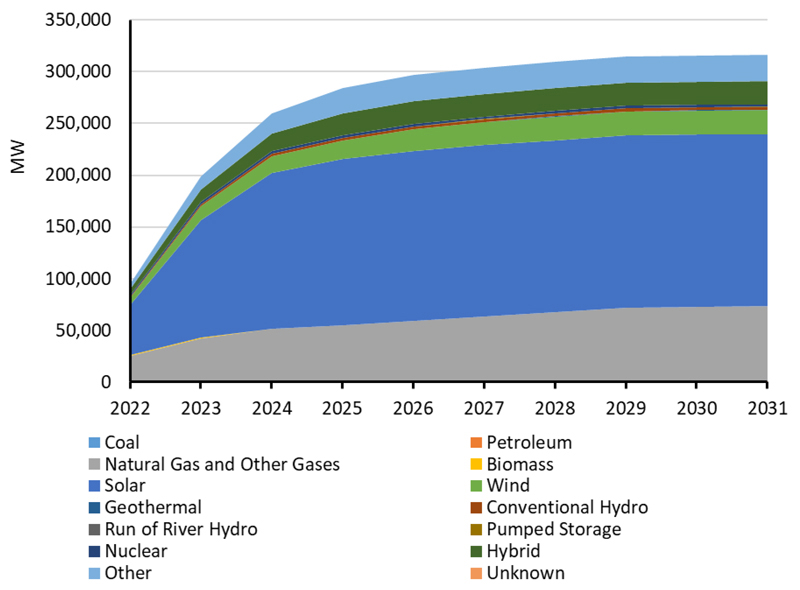

Tier 1 and 2 planned resources projected through 2031. Tier 1 resources are planned capacity that have completed or are under construction, or have a signed/approved interconnection service, power purchase, or wholesale market participant agreement. Tier 2 resources are capacity that have signed/approved completion of a feasibility, system impact, or facilities study; have requested an interconnection service agreement; or are included in an integrated resource plan. | NERC

Tier 1 and 2 planned resources projected through 2031. Tier 1 resources are planned capacity that have completed or are under construction, or have a signed/approved interconnection service, power purchase, or wholesale market participant agreement. Tier 2 resources are capacity that have signed/approved completion of a feasibility, system impact, or facilities study; have requested an interconnection service agreement; or are included in an integrated resource plan. | NERCThe resource adequacy challenge is partially caused by the decommissioning of traditional generators. MISO, for example, is projected to retire more than 13 GW of resource capacity between 2021 and 2024, while the report warned that the planned retirement of California’s Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant could contribute to more than 3 GW of capacity shortfalls beginning in 2026. Across the bulk power system, total capacity retirements are expected to top 60 GW by 2031, with coal making up the majority of plants decommissioned.

NERC’s projections show a steady decline in coal and petroleum generation through 2031, with the greatest growth expected in solar. Natural gas, meanwhile, is set to expand into the gap left by the retiring coal plants.

The more than 100 GW of additions to the BPS over the next 10 years — considering only Tier 1 resources, which comprise completed and under construction projects, as well as those with signed and approved interconnection service or power purchase agreements — are almost entirely solar and natural gas facilities. Other forms of generation, such as wind, petroleum, hydropower and nuclear, account for around 20% of capacity additions, with wind comprising nearly half of these.

With Tier 2 resources added in — those with signed or approved feasibility, system impact, or facilities studies, or that have requested an interconnection service agreement — solar plants are expected to grow from the current level of 41 GW to around 331 GW during the next 10 years. By the same measure, wind resources are set to expand from 132 GW to more than 244 GW over the same period.

The simultaneous growth of gas and solar is no accident, said Mark Olson, NERC’s manager of reliability assessments. Solar panels are naturally dependent on the availability of sunlight, and while the resources planned for addition are sufficient to meet demand at peak hours — typically in the middle of the day — they actually pose a problem later in the afternoon. At these times demand is lower, but the output of solar panels falls off sharply because less light is present, requiring another resource to pick up the load.

“Even though the reserve margins are adequate, energy risks are reduced by having sufficient flexible resources, which are resources that can be dispatched by the operators to follow demand, balance the system and make up for drop-off in variable resources,” Olson said. “And natural gas-fired generation is an important resource, as are effective demand response programs, in helping to reduce risk associated with [that] drop-off.”

Climate Change Makes Demand Forecasting Harder

While the weather restrictions of solar and wind imply that balancing resources should be expanding with them, Olson noted that the opposite seems to be happening in some regions, with “flexible generation resources … falling in Texas, California and the U.S. Northwest.” He warned that without local flexible generation, such areas will be dependent on weather-dependent facilities and external transfers. However, “extreme weather conditions raise the likelihood for one or more of these resources to fall short … leaving other resources to make up for this gap or … load will need to be shed.”

The LTRA noted that this combination of new types of generating resources and growing climate challenges means that existing methods of measuring resource adequacy may not be adequate. In particular, the report noted that the reserve margin — NERC’s traditional metric for reliability, defined as the difference between projected on-peak capacity and forecasted peak demand, divided by peak demand — may be too limited to capture the nuances of new generating resources.

“It’s kind of a simplistic way of looking at one hour and coming to a conclusion for all other hours,” Moura said. “And that’s served us well, and [still] serves us well in certain parts of the [continent] … where you have a lot of dispatchable resources. But in areas where we’re seeing these energy constraints, like in California, the Northwest, and ERCOT, we need to look with a different lens.”

Moura said that NERC has “a close partnership on a project right now with [the] Electric Power Research Institute” to study new metrics for use in planning and decision making. He suggested that industry stakeholders may also draw on work from their counterparts in other countries, without elaborating on what these might be.

“That is only part of the solution because then you … actually have to” create and enforce new standards based on these metrics, he added. “But right now, we’ve got to define this measuring stick to really help and guide what that path looks like going forward.”