The Western Interconnection faces threat of widespread resource shortfalls by 2025 largely because of increased variability in demand and generation, according to WECC’s Western Assessment of Resource Adequacy (WARA), released Friday.

“Both demand and resource availability variability are increasing, and the challenges they present appear worse now than they did in the 2020” WARA, WECC said. “Resource adequacy risks could get worse before they get better if action is not taken immediately to mitigate near-term risks and prevent long-term risks.”

Higher Demand Meets Variable Generation

WECC introduced the WARA last year to supplement NERC’s Long-Term Reliability Assessment (LTRA) because of concern among Western stakeholders that NERC’s analysis did not capture all the risks that the Western Interconnection faced. (See Western RA Planning Must Change, WECC Says.) Like the LTRA, the WARA attempts to identify the biggest threats to the bulk power system over the next 10 years.

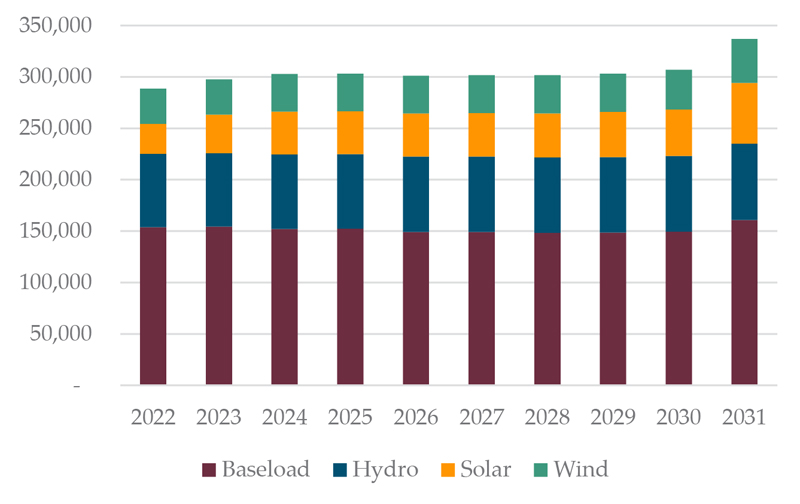

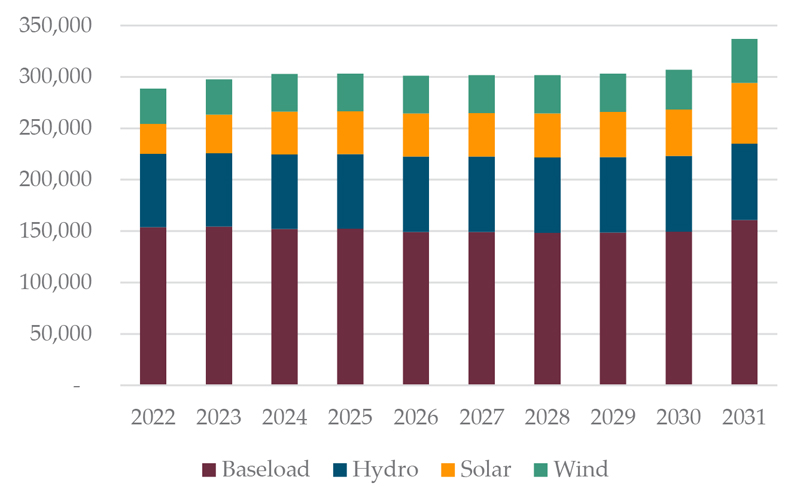

This year’s LTRA, also released on Friday, noted emerging challenges to electric reliability from severe weather events and the move toward weather-dependent renewable resources. (See NERC Identifies 10-Year Challenges from Weather, Resource Mix.) WECC’s report also highlighted these issues, noting that while the interconnection’s “baseload” resources — coal, nuclear and natural gas — are expected to remain “relatively flat in terms of capacity” for the next decade, the capacity of solar resources is set to nearly double over the same period largely because of “new clean energy mandates and … customer demand.”

Forecast of the Western Interconnection resource mix, 2022-2031 | WECC

Forecast of the Western Interconnection resource mix, 2022-2031 | WECC

Although the new resources are technically sufficient to satisfy peak demand, their variability means registered entities cannot guarantee their availability at all times. In addition, increased use of electricity for transportation, heating and cooking means higher demand for these unreliable resources to meet. Consequently, WECC warned that none of its five subregions will “be able to eliminate the hours at risk for loss of load even if they build all planned resource additions and import power.”

To mitigate loss of load, the report’s authors suggested periodically recalculating the planning reserve margin (PRM) anytime there is a substantial change to demand or resource availability to reflect the dynamic nature of the modern grid more accurately. Alternately, WECC could switch from the peak demand PRM that it currently uses, which is calculated based solely on the peak demand hour, to a higher fixed PRM, which the authors hope would ensure entities are prepared for sudden changes in load or generation at any time.

New Study Methodologies Tested

For this year’s WARA, WECC also sought to “deepen the analysis of resource adequacy and provide an assessment of specific scenarios” by adding a deterministic scenario analysis to augment the traditional probabilistic analysis. This study focused on the impact of various extreme scenarios on the ability of balancing authorities to import energy.

WECC tested entities’ export and import behavior across the interconnection under three scenarios: one in which demand and generation for the year conform to the most likely conditions; high demand, simulating one-in-33-year demand level; and drought case, simulating both high demand and no energy from Glen Canyon and Hoover dams. All three scenarios model the same time period: an evening hour in June 22, chosen because it “represents a time of high demand and resource variability.”

Under normal conditions, excess energy generated in the north and east moves toward the south and west, so energy flows out of Arizona, Montana, the Northwest and Northern California and flows into southern Nevada, New Mexico, Southern California and Mexico. But the deterministic analysis “showed dramatic changes in power flow … in both the high demand and drought cases,” WECC said.

During high demand, regions are able to bring reserve resources online to help serve the increased load; Colorado and New Mexico switch from importing power to exporting, while Northern California must switch from exporting to importing power to serve its higher demand. The drought case puts a bigger strain on the system, with Colorado, Arizona and parts of Utah now unable to export power and New Mexico having to increase exports to supply those areas; in addition, more energy must flow out of the Northwest into California to make up for the loss of the two dams.

Despite the growing challenges, WECC sounded a note of hope in the report by noting that there is still time for utilities to address these issues. But the RE warned that action is needed sooner rather than later because options will become more restricted as time goes on.

“Entities have many more options to address resource adequacy issues in the five-to-10-year time frame than in the near-term,” WECC said. “However, it is critical that entities act now to address years five-10 because the magnitude of the resource adequacy challenges increases with time. If the current long-term issues are not addressed immediately, they may be insurmountable when they become near-term issues.”