Utilities can learn as much from their close calls as from their emergencies, but everything depends on the approach they take, presenters said at ReliabilityFirst’s annual Human Performance Workshop on Thursday.

A team from New York-based vegetation management company Lewis Tree Service joined the webinar to share some insights from their close call program, which the company began in 2019. The company defines close calls as events in which an injury or property damage almost occurred, but was prevented either by employee intervention — what the company calls a “good catch” — or events outside their control, which are dubbed “got luckies.”

The company, which has more than 4,000 employees, provides vegetation management services to investor-owned utilities, municipal electric utilities and cooperatives in 27 states.

Beth Lay, Lewis Tree’s director of resilience and reliability, compared the program to NASA’s Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS), which launched in 1976. Lay called the ASRS “groundbreaking” for allowing “good faith mistakes and procedural violations” to be reported without punishment. Lewis Tree wanted to create a similar culture of mutual support and information sharing among its employees.

“What we’re trying to accomplish here is [creating] a learning organization where we’re not only learning from our incidents [of injury or damage], but we’re learning from the day-to-day work that’s going on out there, and what our folks [are] encountering and the challenges that they’re adapting to every day,” said Bret Kent, the company’s training manager.

Overcoming Employee Reluctance

At the close-call program’s launch in 2019, Lewis Tree recognized that its workers already understood that close calls could be useful: employees frequently shared such stories among themselves informally. The challenge was collecting and storing the data systematically so that it would provide the most benefit to the company, while convincing workers that they would not be punished for sharing their experiences.

The company started by defining the information it wanted about each event. Kent said this boiled down to three questions: “What happened, what surprised us and what did we learn that would help others?” This was also the stage at which Lewis Tree identified the “good catch” and “got lucky” categories. While some organizations’ close call programs focus on the second type of incident, Lewis Tree’s leadership felt that incidents in which employees successfully averted injury or damage could also be valuable for training purposes.

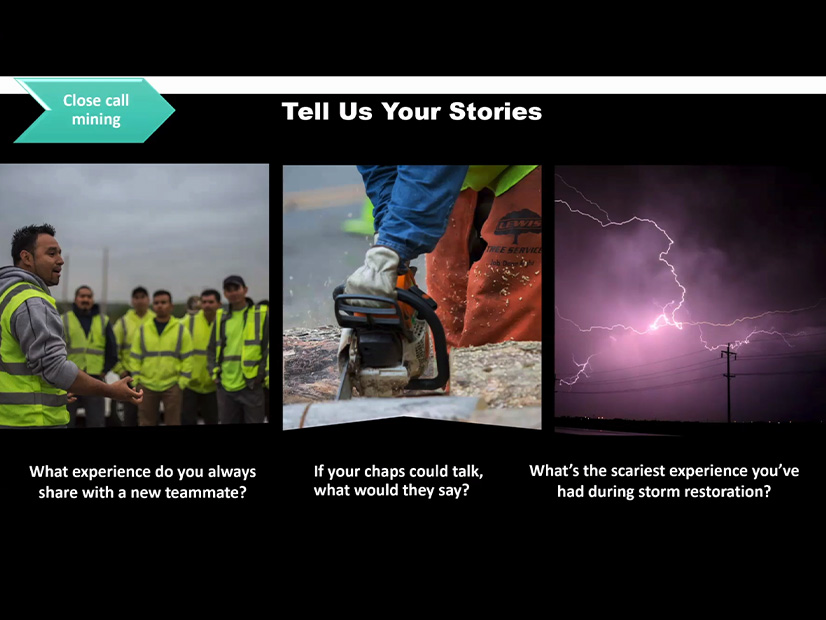

Next, management introduced the program to employees. The rollout initially took the form of what Lay called “close call mining,” in which leaders met with field workers to ask for their stories about memorable events they had witnessed.

Lay described these sessions as informal “tailgate” sessions featuring questions such as “what experience do you always share with a new teammate,” “what’s the scariest experience you’ve had during storm restoration” and “if your chaps [protective clothing] could talk, what would they say?” — a suggestion of Lewis Tree’s COO. The questions were calculated to put employees at their ease.

“It allowed people to share scary, dangerous things that they had seen in the past without fear of any repercussions,” said Kent. “It wasn’t something that they were afraid of reporting because it [had] just happened. … That was really the key to beginning to build trust for people to share openly about what was actually happening on the front line.”

As workers got more comfortable with the program, the company began to move its focus toward reporting more recent incidents. It introduced a smart phone app and a standardized reporting form; submissions are collected into a weekly report and notable incidents are discussed in regular conference calls with management.

Putting Faces to Reports

One area in which Lewis Tree’s close call program differs from similar initiatives at other organizations is that names are always attached to submissions. Kent acknowledged that this step could be intimidating for employees reporting incidents in which they may have made mistakes, but said it was vital to maintain the supportive atmosphere the company desired. Attaching names to reports meant that managers could ask follow-up questions to delve deeper into the event.

In the case of particularly noteworthy reports, management may ask the employee who submitted it to review the event with them. Brian Temas, an area manager with Lewis Tree, recounted a call in which his employees discussed a near-injury by a falling tree. He described management’s attitude as appreciative of the workers; the employees reported that they felt “jazzed” to be included in the review.

“One of the things that we … found very useful was asking the question, ‘What were our workers trying to accomplish here?’” said Temas. “That can sometimes feel as though it’s a loaded question, but through our process … we were able to get our team to understand that this was an honest question to … help not only our leadership team, but everyone on the call.”

The company considers the close call program to be a major success; while just 317 reports were received the first year, Lewis Tree received nearly 3,000 reports in 2022 and so far this year has gotten more than 3,500. Lay urged organizations considering a similar program to keep things as collegial as possible.

“I’ve heard that [for] some organizations, just like … they link mandatory corrective action programs to an incident [of injury or damage], they may think about doing the same [for] the close calls,” Lay said. “I would recommend against it, because I think that would really inhibit people from submitting close calls.

“What happens in these learning conversations is … different leaders in our organization sharing, ‘Hey, here’s a good practice for this’ … and the [employee] who submitted the close call walked off going, ‘I’m going to try these things,’” Lay continued. “Well, multiple other leaders on the call will walk away with those as well.”