A massive solar facility proposed in a small rural town reflects all of the expense, stress and delays that characterize renewable energy development in New York in 2025.

GLEN, N.Y. — Roadside signs sprinkled through this rural town indicate someone nearby is “Saying NO! to MEGA SOLAR.”

But signs sprinkled through state law and reams of case records suggest these residents are shouting into the wind — the state will override local restrictions and objections to allow nearly 2 square miles of photovoltaic panels to be installed on what now is farm fields and woodlands.

Local input will shape the details of the approval, but local opposition will not block it.

The 250-MW Mill Point Solar 1 project Repsol Renewables wants to build in Glen is a microcosm of many of the issues that have put New York behind schedule in its drive to decarbonize its grid.

Building one of those large-scale renewable projects in New York is a long, expensive and fraught process with a lot of strong opinions on all sides. Many things can delay or kill a proposal, but local opposition of the kind seen in Glen is less of a threat than it once was.

With New York’s strong home-rule tradition, its 900-plus towns traditionally have the power to limit or block such development.

So when the state Legislature voted a clean-energy vision into law in 2019, it also created a mechanism to override local opposition, lest the vision die of a thousand cuts at the hands of opponents and elected leaders like those in Glen.

Which is not to say everyone in Glen is opposed.

More than 700 small solar arrays already exist in town, and some residents support Mill Point, which would be one of the largest arrays ever built in New York state.

Speakers at a May 28 public comment session were split between support and opposition. But many of those who spoke in favor would stand to benefit financially, and many of those opposed stood to lose — whether from the aesthetics of so many solar panels or from the feared impacts on the land and community where they and their families have lived for decades, or sometimes generations.

Compounding the resistance is that there is not just one of these huge solar arrays on the table. Multiple utility-scale proposals have been floated in the county, where land is gently sloped and relatively cheap, and where there are multiple major transmission lines.

In response to an even larger solar proposal just west of Glen, the Montgomery County Legislature passed a local law in October 2024 requiring developers to avoid or mitigate the cumulative impacts of the multiple “industrial solar arrays” proposed.

The county then “respectfully” asked the state Office of Renewable Energy Siting and Electric Transmission (ORES) to consider this law as it considered solar proposals. But it could be no more than a request. ORES trumps home rule.

These same issues are playing out in numerous states, as state leaders either expand or limit local governments’ ability to thwart renewable energy development.

Role of ORES

ORES was created in 2020 to smooth the path to the statutory goals of New York’s landmark 2019 climate law, which include 70% renewable electricity by 2030 and 100% emissions-free electricity by 2040.

ORES is intended to streamline and standardize the environmental review and permitting of renewable energy facility proposals with a nameplate capacity of 25 MW or greater; projects rated at 20 to 25 MW also can opt in.

To accomplish this, ORES can waive compliance with local laws that would limit or block a proposal. Glen’s 18-page Solar Energy Facilities Law is a textbook example. It contains such requirements as a 500-foot setback on all sides in areas zoned rural residential, a ban on clear-cutting more than nine acres of trees and a requirement that substations not be visible.

In the draft permit, ORES provides relief or limited relief from nine separate aspects of the town law (Matter 23-02972).

Separately, it found that the 2024 Montgomery County law was not in effect at the time Mill Point was proposed and found that the county’s 2021 scenic byways law also was not applicable.

ORES does encourage public opinion and offers multiple opportunities to submit it.

Straight-up NIMBY statements and opposition to renewables seem unlikely to sway ORES, as it was created to promote renewables and blunt NIMBYism.

Twenty-three of the 39 applications listed on the ORES database have been approved, and all likely faced at least some local objections. But only one application has been denied, and that was because the developer had lost property rights, not because of opposition voiced in the 1,003 written comments submitted in the matter.

Nonetheless, local input is foundational to shaping ORES’ decisions. A spokesperson told NetZero Insider:

“The statements made at the public comment hearing, along with statements submitted in writing, may be used by the [administrative law judge overseeing the case] to determine if there is a sufficient doubt about the applicant’s ability to meet statutory or regulatory criteria applicable to the permit to warrant adjudicatory hearings on the application and draft permit.”

On a more granular level, the spokesperson said, local input is important to identifying impacts of a project and identifying the priorities or concerns of its neighbors.

This can shape ORES’ decision, so that these impacts are minimized while renewable energy development is advanced.

The public comment period on Mill Point Solar 1’s draft permit closed two days after the public comment session.

Project Details

Lead project development manager Andrew Barrett told NetZero Insider the Mill Point Solar 1 team first put feet on the ground in Glen in 2020. They hope to make a final investment decision in mid-to-late 2026, start construction soon after and begin commercial operation by the end of 2027.

This is not an uncommonly long timeline.

Along the way, ORES twice returned the application as incomplete, and Repsol had to put $250,000 in an intervenor fund so that opponents can pay for research and legal challenges.

The process, Barrett said, is “thorough with a capital T.”

The draft permit issued by ORES contains dozens and dozens of stipulations that fill 56 pages (with no appendices, footnotes or punchy graphics to take up space).

New York’s goal is to not damage the environment while trying to save it, Barrett added, which is important to the company and foundational to renewable energy.

And it is a draft permit that Repsol finds workable.

“Other than taking a lot of time and a lot of money, it is good because it does what we would do anyway, which is, forces us to be up there, forces us to be open and transparent with maps and schedules.”

Money has been a problem and may be again. Mill Point was among the huge tranche of renewable projects whose developers canceled their renewable energy certificate contracts with the state in late 2023 when the terms became financially untenable.

Just recently, it won a new contract from the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority — presumably at much higher cost, though NYSERDA is not saying and Repsol holds the information as confidential.

But great financial uncertainty still hangs over the proposal in the potential loss of the federal tax credits created by the Inflation Reduction Act. They are vital to Mill Point, Barrett said, though losing them would not necessarily kill the project. There also is the threat of tariffs.

“There are a lot of moving pieces in this,” he added. “The uncertainty the Trump administration has added recently is not helpful.”

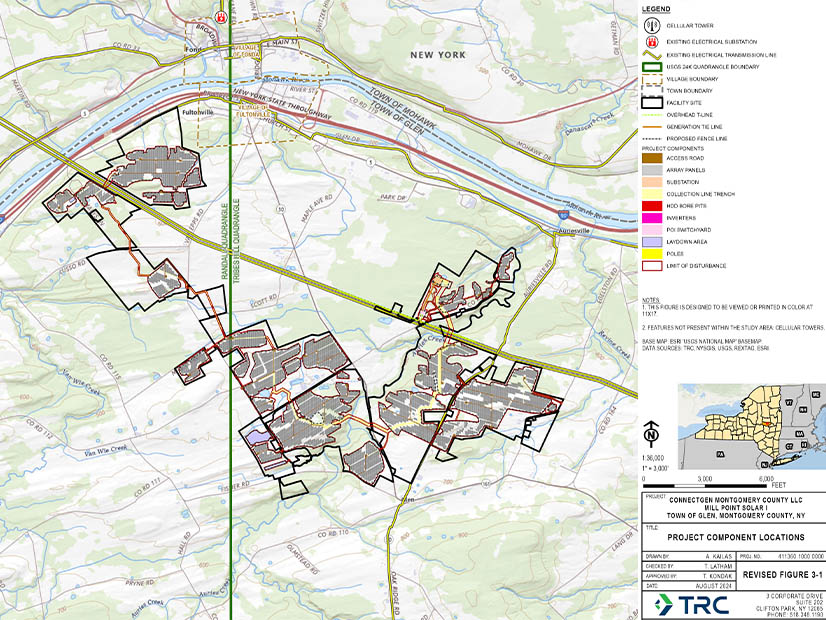

As planned, Mill Point Solar 1 would have a nameplate capacity of 250 MW, operate at a 22% capacity factor and cover about 1,124 acres. Fencing and infrastructure on the patchwork of parcels would push the total footprint above 2 square miles.

Distributed solar already has a foothold in town, where 730 arrays ranging from 0.7 to 6,900 kW were connected to the grid as of March 31.

Utility-scale solar development is not nearly so quick and nimble. But just one completed large project could far outstrip the 83.8-MW DC combined output of those 730 little solar arrays.

Large-scale solar is interested in the county because of its topography and its transmission lines — dual 345-kV circuits operated by National Grid cross right over Mill Point’s proposed footprint. To the south, LS Power and NYPA have 345-kV circuits that recently were enhanced to carry more upstate renewable energy to the downstate market. Additional smaller lines cross the area.

NYISO’s 2025 system map shows that this concentration of transmission is uncommon in upstate New York.

NYSERDA and the Department of Public Service looked specifically for areas that contain this combination of relatively flat land near transmission as part of the effort to accelerate large-scale solar development in New York.

“Montgomery County was identified by NYSERDA and DPS as having strong potential for such project sites,” a spokesperson said.

Other projects in the county include the 300-MW Flat Creek Solar, now under review by ORES. NextEra has the 90-MW High River Energy Center. Repsol also plans the 100-MW Mill Point Solar 2. Avangrid proposed the 90.5-MW Mohawk Solar. Greenbacker won a NYSERDA contract for the 20-MW Tayandenega Solar. SunEast Development won an 80-MW contract. And that is only a partial list.

Some of these proposals have been canceled or shelved, and others may never break ground. But the steady flow of proposals has dismayed a vocal segment of the county.

Push and Pull

The May 28 meeting showed the depth of local division, seldom more clearly than when the top elected official in Glen and his predecessor took the mic for their allotted three minutes.

“Small, rural towns with large agricultural open land holdings, limited budgets, like the town of Glen, are the target of these energy companies,” Town Supervisor Timothy Reilly said, “because in the context of New York state, we have insufficient funds and other resources to sustain a legitimate fight of these projects on a level playing field.”

Former Town Supervisor John Thomas countered: “There are far too many falsehoods being bandied about regarding the supposed evils of solar energy — I’m sure you will hear some of these tonight. The amount of energy from the sun hitting the Earth in one hour could power the world for an entire year. Solar energy is essential to combating climate change.”

In the following two hours, the comments volleyed back and forth with a rhythm of opposition and support.

This will destroy prime farmland.

Anyone who calls this prime farmland has never farmed it.

This will affect our Amish neighbors terribly.

A lot of the Amish are craftsmen more than farmers.

We’re trading in our agricultural heritage and future for a temporary source of electricity … and to benefit a corporation … and for little financial benefit to the community.

I can’t afford to farm … or farming is hard work that I’m getting old to do … or I don’t want my son to follow me into farming.

We’re being asked to trade our dreams for someone else’s vision of progress.

Would you rather see another warehouse there?

All this solar electricity is going downstate.

I have a right to do what I want with my land.

Not if it contaminates my land.

Construction will provide work for my union members.

This solar farm will create almost no permanent jobs.

Not Keeping up

There is much to unpack in those comments.

Montgomery County is like most of upstate New York: farmland and wooded former farmland dotted with villages and hamlets that date to the 1700s and 1800s. Commercial and industrial operations large and small survive and even thrive but occupy only a tiny fraction of the landscape. Its only city bears the scars of industrial decline and 1970s urban renewal.

Montgomery County’s population dropped more than 11% from 1970 to 2020 while the nation’s grew more than 62%. The percentages of county residents older than 65 and younger than 18 are both higher than the national average.

In other words, some young people look elsewhere for opportunity, and some never come back.

Farmland has been going out of production for a century, but a local statistic stands out in the ag census the USDA publishes every five years: There are many more small farms in Montgomery County now than in the 1990s, even as the amount of land in active production has continued to shrink.

The number of farms statewide decreased 20% from 1997 to 2022 but only 3.6% in Montgomery County.

This trend at least partly is due to a large influx of Amish attracted by one of the things that solar developers appreciate: affordable land suited for their purposes.

A large contingent of Amish men attended the May 28 comment session. But in keeping with their Old Order ways, they sat in a cluster and listened to their “English” neighbors speak, rather than offer comment themselves.

It was a bit ironic, given that some of them may not even use electricity. But the land-use debate does bear directly on the Amish.

The state in 2024 authorized eminent domain for transmission siting, but there is no such provision for solar power — if a photovoltaic array is placed in a pasture, it is with the landowner’s permission.

So the Amish need not lose the land they have. The concern may be more for the future and the options Amish children will have if farmland is scarce by the time they grow up.

Common Ground

At the May 28 public session, a third-generation town resident went in a different direction than other speakers and wondered why state policies did not offer more support for agriculture, so that farmers were not forced to make these hard choices about their land.

“I hate to see our community divided like this. It really breaks my heart,” she said.

It certainly is divided, but the tone throughout the evening was civil, not hostile.

“I think that the civility of the meeting, I think that comes with time,” Reilly told NetZero Insider later. “I think we have really come from becoming adversarial to each other and [those] kind of comments to a more participatory type of meeting where, ‘Look, I just want to get my point across.’”

Town Board meetings and community meetings hosted by the developer helped smooth that out, he said.

“It was a tribute to both sides for that,” Reilly said.

Unprompted, he added: “Andrew [Barrett] has been nothing but a gentleman since day one. You know, he comes in here and we sit, and we visit. We could almost go fishing together, but we’re on opposite sides.”

Barrett said this is the nature of his role and the job of others like him around the state and nation as they look for enough land and enough of a consensus to put together viable projects.

After the company identified Glen as a potential large-scale solar site, the development team was on the ground introducing themselves and explaining what they wanted to do as they looked for potential leases.

“Honesty and transparency is important, and we think it makes a difference,” he said.

And it is important not just to listen but to process what is said. After dialogue with the community, for example, Repsol moved the project footprint away from a cemetery and away from the historic hamlet at the center of the town. That soothed some feelings, but far from all.

“Twenty-five hundred people are never going to agree perfectly on any topic, certainly a large project like this,” Barrett said. “You’re always going to have someone who thinks this is a good idea because we need it for the environment, someone who would like to participate because it helps them save their farm. And then you will get people that are across the street and don’t like the look of panels, even if they’re going to be well screened.

“You’re not going to win over everybody.”

Reilly said the problem for him is not just the state usurping home rule but doing it to push through something that will start depreciating soon after it is installed.

“Much of the resistance, I think, in the town is not necessarily for renewable energy. It is the consumption, the vast consumption, of these huge swathes of land for something that’s going to be outdated in 30 years.”

But Reilly said the town is not ready to concede.

“I don’t think people think it’s a done deal by any stretch of the imagination,” he said. “You know, there are some that think, ‘We’re it’s the ninth inning, and we’re down a lot of runs.’ But as Yogi Berra would say, ‘It’s not over till it’s over.’”