The geothermal electricity sector continues its slow growth in the U.S., but the cost of next-generation technology has fallen sharply, setting the stage for wider expansion.

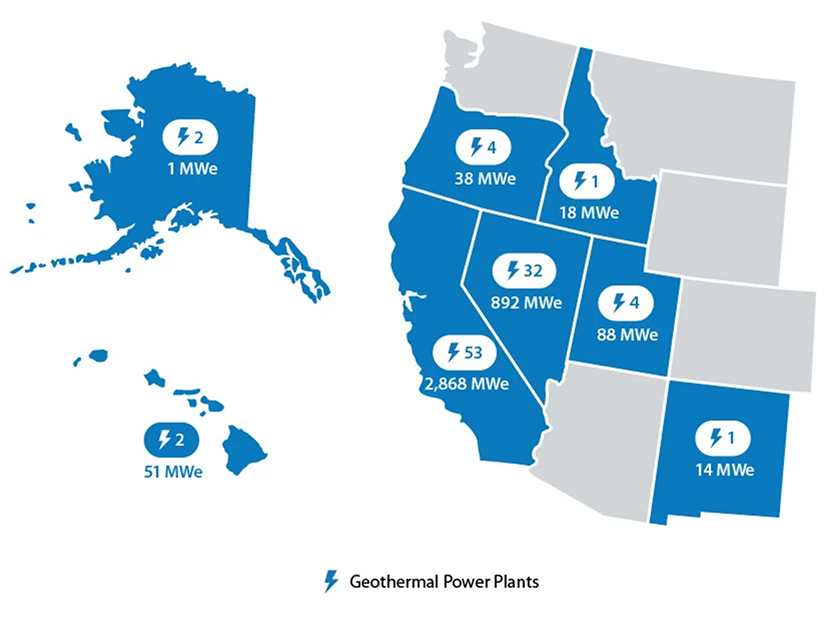

The 99 U.S. plants online in 2024 had a combined nameplate capacity of 3.97 GW, up 8% from 2020, a new report indicates.

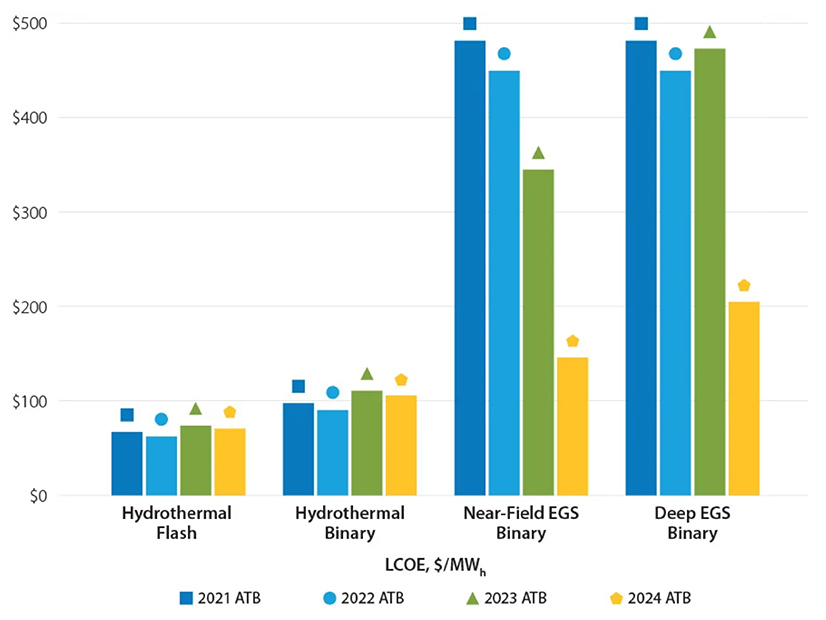

Over the same time frame, the levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) for conventional geothermal technology held relatively steady at $63 to $74/MWh for flash plants and $90 to $110/MWh for binary plants. With reported geothermal power purchase agreements running in the $70-to-$99/MWh range, the authors say, these LCOEs are considered investable for a firm, high-capacity factor source of electricity.

While the LCOE for enhanced geothermal systems (EGS) remained significantly higher — as much as $200/MWh in 2024, depending on technology — it was close to $500/MWh just three years earlier.

Recent advances could lower the cost of EGS to the level of conventional geothermal technology by the mid-2030s, the authors write.

The details come in the “2025 U.S. Geothermal Market Report,” issued in January by the former National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) and nonprofit advocacy group Geothermal Rising.

The Trump administration recently renamed NREL the National Laboratory of the Rockies, an indication and reflection of its energy priorities. However, geothermal energy is among the few components of the renewable energy sector in favor with the current administration amid its push for more oil, gas and coal combustion.

Recent advances in oil and gas extraction techniques have brought down drilling costs in that sector. While geothermal drilling remains more expensive than oil and gas drilling, its costs have declined as well, which is important — drilling accounts for 29 to 57% of the total cost of developing a geothermal field, according to the report, which is an expansion of a 2021 NREL report.

However great its potential, geothermal was a minimally used resource in 2024, accounting for only 15,407 of the 4,308,634 GWh of electricity generated nationwide in all utility-scale sectors, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

The 8% increase in U.S. geothermal generation from 2020 to 2024 was higher than the 7.4% increase for all types of utility-scale generation over the same period.

Geothermal nonetheless remained one of the least used technologies — wood and other biomass fuels were burned to make three times as many watts as geothermal generated in 2024.

But the report makes an optimistic case for the potential of the earth’s heat to generate more electricity and to heat or cool more structures in the United States.

It indicates the number of geothermal projects in development increased from 54 in 2020 to 64 in 2024 as research improved replicable EGS processes with substantial decreases in drilling time.

As of late 2025, 29 states had enacted geothermal incentive policies, 17 of which encourage geothermal electricity production.

The authors further present geothermal as a component of U.S. energy security and independence: a potential power plant for data centers, a potential option for hybridization with thermal storage and a potential source of critical materials from the extracted underground brine.

A recent analysis by the laboratory estimated 27 to 57 TW of EGS potential at a depth of 0.62 to 4.3 miles across the continental U.S. Approximately 4.4 TW of that is in areas under federal management, but only about 1% of it would be considered economically developable.

California and Nevada remained the center of the U.S. geothermal sector as of 2024, the sites respectively of 53 and 32 of the nation’s 99 facilities.