By Tom Kleckner

AUSTIN, Texas — When Diego Villarreal looks north across the Rio Grande toward Texas, he sees a deregulated energy market that looks very much like his country’s.

That stands to reason: Mexico has borrowed the best elements of competitive markets from around the globe and learned from U.S. “success stories” — including ERCOT.

In less than four years, Mexico’s electricity sector has been transformed from a state-run monopoly into a burgeoning marketplace where energy, capacity, financial transmission rights and clean-energy certificates are traded in day-ahead, real-time and capacity markets.

Villarreal, the deputy managing director of electric industry coordination for Mexico’s Ministry of Energy, takes understandable pride in the transformation.

“Where we are right now … that basically took Texas about 10 years,” he said during last week’s Infocast ERCOT Market Summit. “We have been working nonstop to get it where it is in only three and a half years. Yes, there are some elements missing, but keep in mind, it’s only been three and a half years.”

Key to the market’s reform, Villarreal told his audience, was the concept that Mexico “is not an isolated island,” but part of a regional market where “integration can lead to lower prices and more generation” — all of which could be quickly disrupted if the Trump administration continues to insist on building a large physical wall, or “larga barrera física,” along the border.

“It goes without saying that integrating with the United States … is, and was, an essential assumption of the reform,” Villarreal said. “But recent political changes have put that into question.”

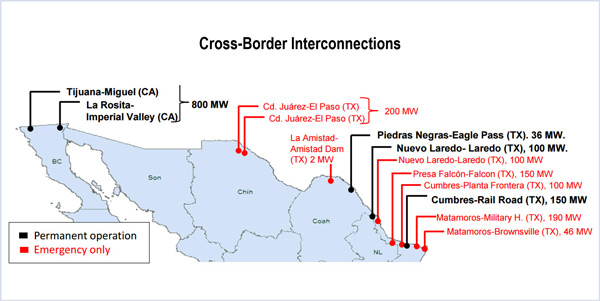

Mexico already has five DC ties with the U.S. — three across the Texas border and two with California — with a total capacity of 1,086 MW. Another eight interconnections provide an additional 788 MW of capacity of emergency power.

Mexico’s natural gas market is just as integrated, with more than a dozen pipelines connecting with the U.S.

Noting that he is not part of Mexico’s negotiating team with the U.S., Villarreal told RTO Insider, “The idea is to find a way for both countries to keep on having a positive relationship with respect to energy trade. The underlying assumption is this will still happen.”

But Villarreal also thinks there’s now a “wild card”: Changes to the free-trade agreement between the two countries could result in “strange consequences” — such as a “very onerous” process for permitting gas exports south of the border.

The Comisión Federal de Electricidad (CFE), the government electricity monopoly, has been broken up into seven generating subsidiaries, which bid into the day-ahead market along with several international generators. Those independent producers include Spain’s Iberdrola and Global Power Generation and several new Mexican companies, and could potentially include American generators.

“Some very large [American companies] that you’re very well aware of … will be transacting in the market very soon,” Villarreal promised. He pointed out that LMPs in Mexico are double those in ERCOT, which averaged $24.62/MWh last year, and said a “very healthy price differential” has been driving flow from Texas across DC ties that are “half-used” during summer’s high demand.

Mexico’s forecasted load growth can serve as a buffer for ERCOT’s oversupply and aggressive wind program, Villarreal noted.

“It’s money lying on the floor,” he said. “Someone has to pick it up. It’s going to go away as people come into the market.”

Gas trade between the two countries is much more mature, and Mexico is a natural sink for the U.S., Villarreal said, noting that his country’s supplies are rapidly being depleted and are bedeviled by high quantities of nitrogen. As the Mexican gas market goes, so goes the electricity market: Half of the country’s generation capacity (68 GW) comes from combined cycle plants.

“If the USA no longer considers Mexico a free trade partner [under the North American Free Trade Agreement], then exports will require a public-interest review … and then an environmental review,” Singer said. “Getting a permit to export gas to Mexico today is a very simple process. Representing the Mexican government, if we can’t get that gas, it will really be problematic for the system. But it’s also really problematic for Texas.”

But Villarreal prefers a more optimistic outlook.

“I think the underlying assumption is that the gas trade between Mexico and the U.S. will continue to flourish,” he said. “No investment on the gas infrastructure has been stopped. Nobody is saying, ‘Oh, don’t build that pipeline.’ On the power side, we’re working under the assumption that gas will not stop flowing from the U.S. into Mexico.”