The Home Energy Efficiency Team (HEET) is developing a way to transport heat from the Merrimack River in eastern Massachusetts to houses using geothermal technology.

Eventually, the nonprofit plans to use heat from Massachusetts Bay to keep homes warm during the cold New England winters, Co-executive Director Zeyneb Magavi told NetZero Insider.

Drawing heat from a river or the ocean uses technology that is similar to ground source heat pumps.

Massachusetts is one of the most developed states in the country, and its densely packed houses leave little room for new infrastructure. More than half of the state’s housing stock relies on natural gas, but Magavi said geothermal heat pump systems can run in the same rights of way that gas pipelines occupy, creating a decarbonization pathway for the industry.

“Instead of delivering gas, we are delivering water at specific temperatures,” Magavi said.

Gas utilities could manage a system-wide geothermal network while retaining their workers for the maintenance and construction of geothermal lines and pumps, Magavi said.

And while gas prices fluctuate, heat from the river or the bay is always free, she added.

Mark Sandeen, president of MassSolar, and Magavi estimate that lowering the temperature of the Merrimack River one degree with geothermal technology would produce 500 MW of thermal energy while benefiting the warming river ecosystem.

Applying the same thermodynamic principals to remove heat from ocean water would be restorative for the Massachusetts Bay, which is part of one of the fastest warming ocean waters in the world.

Pulling thermal energy from water is “cheaper, safer and more reliable” than natural gas, HEET Co-director Audrey Schulman said. Heat pumps can be placed under docks in the harbor or contained within concrete boxes on the side of the Merrimack River.

“A loop of pipe curled at the bottom of a river doesn’t interfere with the water, it just absorbs the temperature,” Schulman said.

The water in the tube at the bottom of the river would run colder than the water in the river, but slowly become warmer by soaking the heat out of the river into its water in the tube, bringing that temperature through a pipe system to houses and buildings.

Heat pumps allow utilities to control the speed of the energy transfer. If the system is run through the ground in the street directly to homes, there is “almost no thermal loss,” Schulman said.

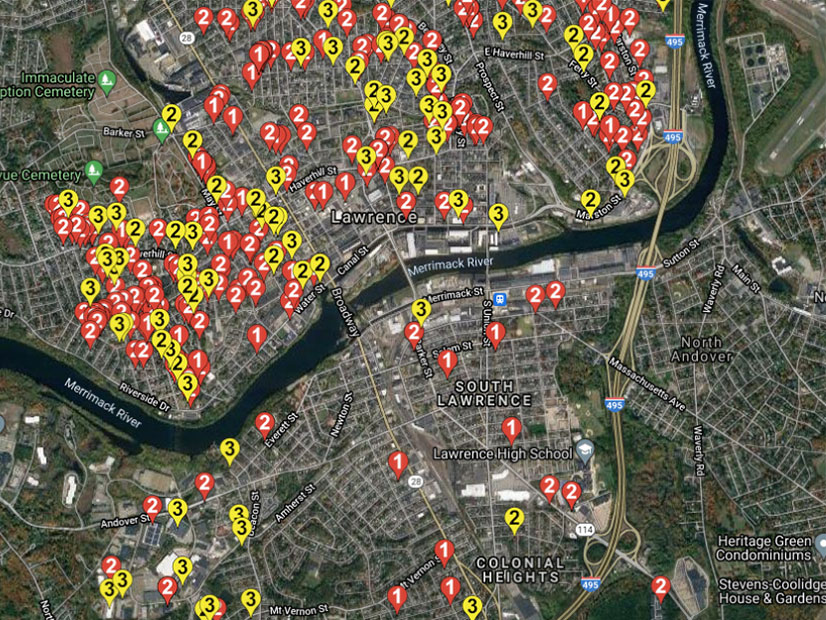

Following a natural gas disaster in Merrimack Valley in 2018, students from Harvard University’s Climate Solutions Living Lab researched the viability of a Merrimack River source heat pump to heat homes. The system would serve low-income and minority communities in Lawrence, Mass.

Excessive pressure in natural gas lines owned by Columbia Gas caused a series of explosions and fires in 40 homes in the valley. Advocates in Massachusetts are pushing for alternative forms of energy to avoid similar tragedies in the future.

With only water in the pipes, geothermal energy does not pose an environmental hazard, Schulman said.

After screening various project sites, the Harvard lab project called for a three-phase approach to adoption of river-source geothermal in Lawrence, including a pilot project run by the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (DEP). The lab also suggests an initial expansion of the pilot by two blocks before scaling up the energy system to more than 430 residences in Lawrence.

The report gives a wide cost range — between $123,000 to $481,000 — for the DEP pilot because the technology is new and there is uncertainty around the scale of the geothermal industry in the future. As proposed, however, the system would generate an estimated 1,600 alternative energy certificates, worth between $25,600 to $32,000 per year.

The pilot phase of the project would also reduce GHG emissions by 63 metric tons annually, and a larger district energy system would eliminate 510 metric tons of emissions from the air annually. Emissions from thermal energy systems would drop even more as the grid shifts to renewables.

Massachusetts is set to release a request for proposals for a competitive grant to build a networked geothermal project in the Merrimack Valley, run by the attorney general’s office.

“We are hopeful something really innovative can happen here,” Magavi said.