The U.S. cannot afford to spin its wheels in developing its domestic supply chain for electric vehicles and the lithium-ion batteries that power them, say two new reports — one from Bloomberg NEF and the other from the White House.

Zeroing out transportation emissions by 2050 will require getting 218 million EVs on the road worldwide by 2030, says the BNEF Electric Vehicle Outlook 2021. But in a business-as-usual scenario with no major policy changes, the 2030 global fleet could max out at 169 million EVs, the report says.

At just 12% of the global market, the U.S. is already running a distant third behind China and Europe in EV adoption and is not expected to catch up, the report says, even with a growing number of “more compelling local models” on sale, along with incentives and other policy initiatives.

China’s leading role in battery production is also a key concern in the White House analysis of the need for federal action to help build out an extensive U.S. supply chain for lithium-ion batteries, which is part of a larger study on building resilient supply chains and revitalizing American manufacturing.

“It is critical for the United States to leverage our leading position in research and development (R&D) of new technologies with a comprehensive set of domestic and international initiatives to accelerate commercialization throughout the battery supply chain,” the report says. “This strategy would translate to well-paying jobs throughout the United States and represents a once-in-a-generation opportunity to position the United States as a global leader in the manufacturing of energy storage materials and technologies to protect both the environment and our economic and national security interests.”

Citing figures from the Department of Energy, the report says that jobs in the U.S. EV market grew from 198,000 in 2016 to 242,700 in 2019.

President Biden has been bullish on the need for the U.S. to win the global EV market, which the BNEF report estimates will be worth $7 trillion between now and 2030 and $46 trillion by 2050.

The president’s 2022 budget includes $137.4 billion over the next decade to spur EV adoption, along with another $20 billion for electric buses. Now mired in partisan gridlock in Congress, the president’s ambitious infrastructure plan sets a goal of having a national network of 500,000 EV chargers installed by 2030. (See Clean Energy Wins, Fossil Fuels Lose in Biden Budget and Biden Infrastructure Plan Would Boost Clean Energy.)

The challenge, the White House report argues, is that the playing field in global EV markets is far from even. The European Union has set a goal of having 30 million EVs on the road by 2030, and individual countries, such as the United Kingdom and Germany, are providing a range of incentives to spur sales, as well as government support to build domestic supply chains.

“China has positioned itself as a market leader in the manufacturing supply chain through the practice of questionable environmental policies, price distortion, state-run entities that minimize competition, and large subsidies throughout the battery supply chain,” the report says.

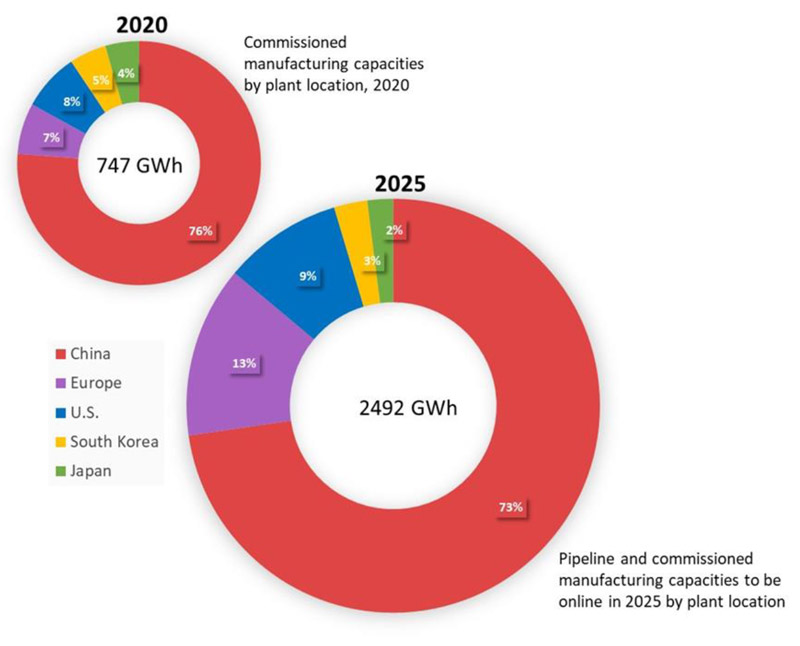

For example, the report projects that by 2025, China will account for 73% of global battery cell manufacturing, down just 3% from its 76% market share in 2020. Citing figures from Bloomberg, the report also notes that a U.S. EV market dependent on batteries manufactured abroad could result in import costs of $100 billion by 2040.

‘Fully Circular Industry’

BNEF calls for an “immediate increase in policy action” to bend the worldwide EV adoption curve toward net zero, especially in the medium- and heavy-duty vehicle sector where, the report says, 95% of all truck sales will need to be zero-emission by 2040.

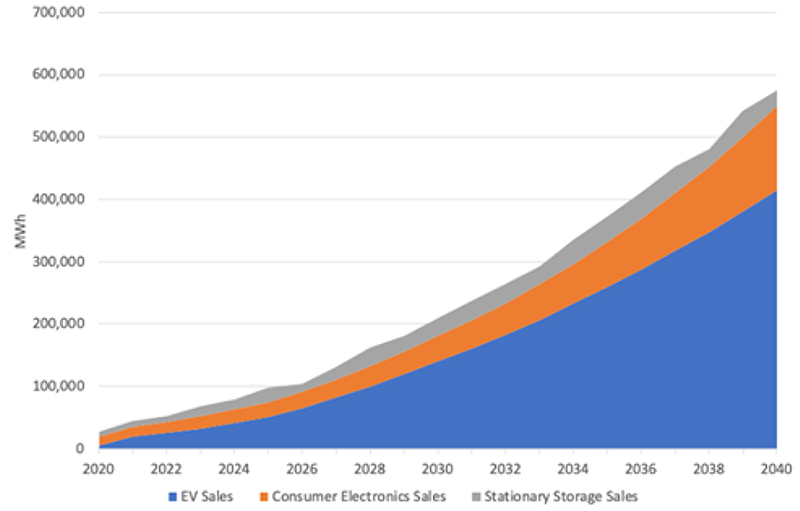

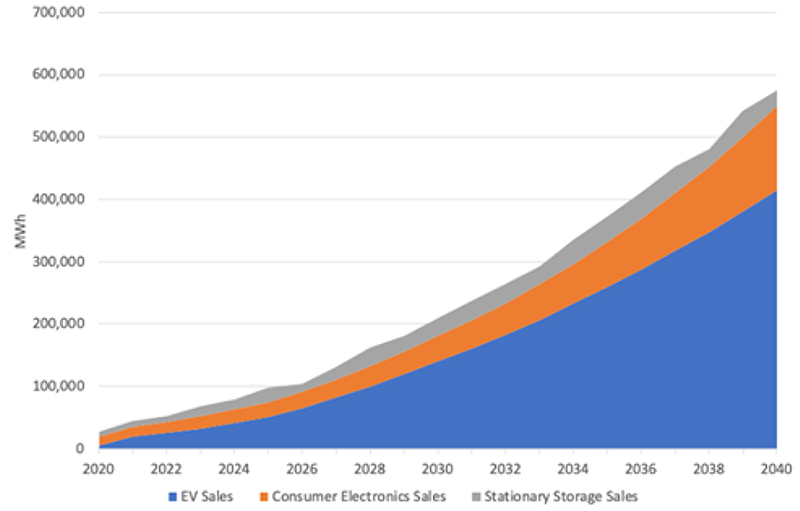

In terms of the battery supply chain, BNEF’s business-as-usual scenario anticipates global demand will grow 15-fold to 2,576 GWh by 2030. A net-zero scenario will require “universal battery recycling,” without which demand for lithium will exceed supply by 2050. A “fully circular battery industry” would provide a “supply of recycled lithium exceeding total annual demand by midcentury,” the report said.

Building a domestic supply chain in the U.S. will depend first on guaranteeing domestic demand, which is where the recommendations in the White House report begin, drawing on policies and priorities already outlined in Biden’s infrastructure plan and budget. Electrifying the federal, state, local and tribal fleets tops the list, with funding initiatives that would also support using domestically manufactured batteries.

Electrifying the 640,000 vehicles in the federal fleet would support 64 GWh of domestic battery production, while state, local and tribal fleet electrification would add another 200 GWh of demand for U.S. manufacturers, the report says. Procurement of stationary batteries for federal facilities should also be leveraged to build domestic manufacturing.

Cell manufacturing capacities | Benchmark Mineral Intelligence

Cell manufacturing capacities | Benchmark Mineral Intelligence

But, domestic manufacturing, in turn, depends on a domestic supply of raw materials and processing capability. The White House report says the U.S. Geological Survey estimates the U.S. has 21 million tons of “economical lithium reserves in various forms.” It also cites a number of lithium extraction projects under way, such as the Rio Tinto demonstration plant in California, which is producing lithium from mining waste. If successful, the plant could be scaled to produce 5,000 tons of lithium per year, the report says.

Other recommendations include:

- increased support to the USGS to improve resource mapping to help with policy and decision making;

- investment in research, development and commercialization of technologies that improve lithium yield and processing and could be licensed to international customers; and

- establishment of a national battery recovery and recycling program, with targeted incentives to increase recycling.

Similarly, the report calls on Congress to “establish a cost-sharing grant program to support cell and pack manufacturing in the United States. This model helps entrepreneurs who do not have the ability to access tax credits in the short run while ensuring the taxpayer shares in the upside of the investment.”

Losers and Winners

The BNEF report is heavy on numbers but also contains some interesting and unexpected insights. It notes that sales of passenger vehicles powered by internal combustion engines peaked worldwide in 2017 and are “now in permanent decline.” Although passenger EVs only account for 1% of global auto sales at present — about 12 million on the road — the report expects a more than four-fold increase to 54 million by 2025.

The gasoline industry is the big loser here. BNEF says gasoline consumption has already peaked in the U.S. and Europe, with a global peak coming in 2027. Even in the business-as-usual scenario, EVs and fuel cell passenger vehicles cut oil demand by 21 million barrels per day by 2050.

For government, this transition will mean a loss of tax revenues from fuel sales and the need to plan ahead. “Politically acceptable solutions for this will vary by region,” the report says.

The electric power industry gets a substantial boost, with global demand up 9% by 2040 in a business-as-usual scenario and 14% in net-zero — with the largest increase in demand coming from medium- and heavy-duty trucks. Full decarbonization of transportation would increase global electricity demand by 8,524 TWh by 2050, the report says.

BNEF also suggests that, over time, battery packs could get smaller, which could ease supply chain demand for critical minerals.

“There is a strong argument for governments investing heavily in public EV charging infrastructure networks because denser networks can help enable much smaller battery packs, leading to further economic and environmental benefits. Switching to vehicle regulations based on life cycle emissions could also help push the market to smaller battery packs,” the report says.

But the report also believes EVs are not the only way to get to net-zero emissions in transportation. “Investments in public transit and active mobility [such as walking or bicycling] are an important part of the solution mix for net zero, as they can reduce demand for vehicles and vehicle miles, while also delivering a public-health benefit. Even a modest 10% reduction in total kilometers traveled by car globally in 2050 can make the task of achieving net zero much easier.”