Maryland has several “technologically feasible pathways” to eliminate direct greenhouse gas emissions from its buildings by 2045, according to a study presented to stakeholders Tuesday.

Achieving the goal will require “technology commercialization and accelerated implementation,” said Charles Li, a managing consultant with Energy and Environmental Economics, Inc. (E3), who presented results of the study, at an online meeting of the state’s Greenhouse Gas Mitigation Working Group Buildings Ad Hoc Group. The group answers to the Maryland Commission on Climate Change.

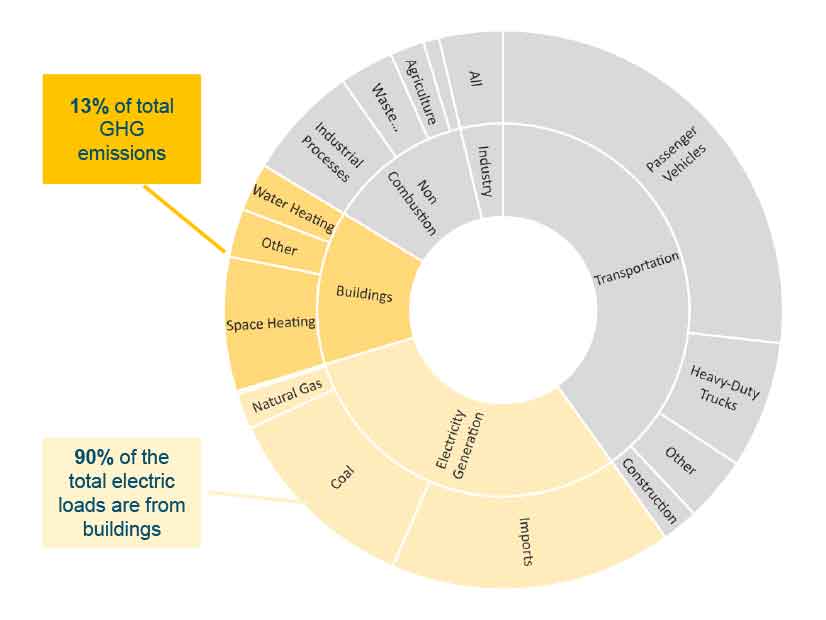

Li cited 2017 data that building direct-use emissions account for 13% of economy-wide GHG emissions in Maryland; buildings also represent 90% of the statewide electric load, which contribute to upstream emissions in electricity generation. In response to a question from David Smedick of the Sierra Club, Li acknowledged those indirect emissions do not include upstream methane leakage. Methane is a far more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide but has a shorter half-life in the atmosphere.

E3 analyzed three scenarios for building decarbonization:

-

-

- High electrification, in which almost all buildings switch to air source heat pumps or ground source heat pumps, with heating supplied by electricity throughout the year, and efficiency improved through building retrofits.

- Electrification with gas backup, in which “existing buildings keep using fuels for heating and are supplied with a heat pump combined with existing furnace/boiler that serves as a backup in the coldest hours of the year,” while new buildings would be required to have all-electric heat.

- High decarbonized methane, in which “buildings keep using fuels for heating while fossil fuels are gradually replaced by low-carbon renewable fuels.”

-

Under the “high electrification” scenario, there would be a shift in peak electricity demand from summer, when it currently occurs, to winter, and that peak would be significantly higher. That would result in “high incremental electricity system costs.”

Under the “electrification with gas backup” scenario, the system cost for electricity would be 80% lower than in the “high electrification” scenario, leading to the lowest overall resource costs of any scenario.

The “high decarbonized methane” scenario would require large amounts of zero-carbon fuels, leading to “high incremental fuel costs with significant cost uncertainty.”

“In all scenarios, all-electric new construction is far and away the cheapest option” for buildings, Li said. Buildings’ electricity demand in all scenarios is lower than it would be under current policies (the “reference scenario”) due to energy efficiency gains. Natural gas demand declines in all scenarios due to energy efficiency gains and fuel switching. All scenarios reduce total energy demand from buildings. Natural gas expenses are hard to estimate under any scenario due to high uncertainty over commodity costs.

Maryland would have little electric peak load growth under the high decarbonized methane scenario, and that which did occur would be due to growth in the number of households and the economy, E3’s analysis indicates. The “electricity with fuel backup” scenario has much smaller winter peak load growth. Meeting electricity demand under the “high electrification” scenario would require about $2 billion to $3 billion in annual incremental system costs — “significant investments,” Li said. “High electrification” also would lead to more rapid rate increases compared to “electricity with fuel backup.”

In answering a question about how the form the U.S. electrical grid takes in the future might impact E3’s analysis, Li said E3 had followed the assumptions about Maryland’s grid from the 2030 plan for meeting the goals of the Greenhouse Gas Emission Reduction Act. Under these assumptions, he said, “Maryland would rely heavily on in-state solar generation, along with offshore wind, and will continue to rely on import resources.”

Christopher Beck, climate change program policy chief for the Maryland Department of the Environment, said at the end of Tuesday’s meeting that “Phase 2 of the process” is beginning and MDE will send out meeting minutes and updated questions. He encouraged members of the ad hoc group “to come back at the next meeting with some policy questions and recommendations, separated out by building category. Over the next three meetings, we will dig in a little deeper on policy priorities and make recommendations to the larger mitigation group.”