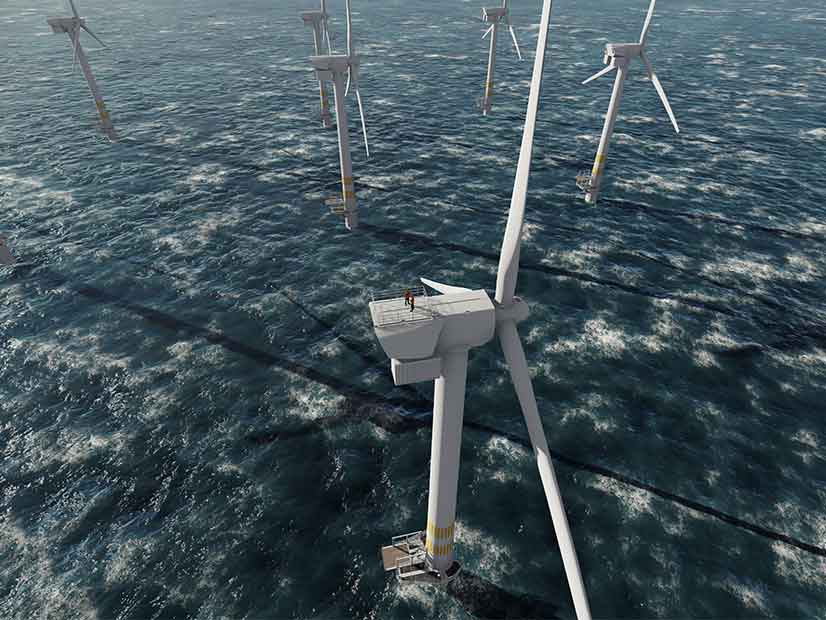

East Coast states that have embraced offshore wind development will soon face wholesale redevelopment onshore — from rebuilding and expanding ports to constructing new roads and even demolition and reconstruction of entire parts of communities — all of it to accommodate the massive components that will be delivered, stored or manufactured for the sea-going turbines.

“The equipment is getting larger by the year. And these cities on the East Coast, they are small older cities, [with] small roads,” Will Roberts, president of Seattle-based Foss Maritime, a maritime services company, pointed out this week in a virtual webinar produced by Our Energy Policy Foundation, a D.C.-based nonprofit focused on U.S. energy policy issues.

Roberts, who has been involved in European offshore wind projects, said cities there have “spent a ton of money and resources” ensuring that the ports and roads can handle the components.

“I think it’s an exciting time with the infrastructure bills that are going into place, but we need to understand that our ports are not set up for the size and scale of what the wind market will bring,” he said. “We can say that we’re bringing everything in by water, but the roads piece is a very interesting piece. Just look at a map of New Bedford, Mass., and tell me which large piece of equipment you’re going to bring in through the roadways there.

“If you go to Belgium or to the Netherlands, you’ll see whole towns that have been reconstructed in order to move that equipment through the city. And you know they’ll shut down whole parts of the city in order to get that equipment through.

“That’s the commitment that the Europeans have made to their offshore wind, and that is something we need to focus on in the United States.” he said.

Still more to consider is that offshore wind development, beginning on the East Coast, is just one part of the Biden administration’s decarbonization drive to move the nation toward net-zero-carbon emissions by 2050.

Another is decarbonizing industry, and the webinar looked briefly at possibilities of decarbonizing the manufacturers of wind turbine components and vehicles: trucks, barges or any of the numerous other water vessels involved in building an offshore wind farm.

“Are there opportunities to approach that investment in a way that decarbonizes the associated industries with offshore wind?” asked webinar moderator Benjamin Huffman, a lawyer concentrating on energy and infrastructure projects with the Chicago-based law firm Sheppard Mullin.

It won’t happen if developers are looking for the lowest bid, Roberts answered.

“If you’re going to talk to an operator like Foss, and you’re going to ask us to do something that’s 30 to 40% more expensive in capital, then I hope you’re going to be with us for the next 20 years,” he said. “It needs to be deliberate and there needs to be a commitment.”

Developers planning the extraordinarily massive offshore projects have one “tailwind,” as the panel members referred to the expansion of the federal 30% investment tax credit by Congress in December 2020.

Aimed at boosting offshore wind, the credit gives developers until the end of 2025 to begin construction and then another 10 years from when construction begins to completion, said Samantha Buechner, a San Francisco-based director at Wells Fargo who specializes in renewable energy tax equity financing. The company in February announced that it had surpassed $10 billion in tax-equity investments in wind, solar and fuel cell industries.

“That is huge and provides a lot of runway,” Buechner said of the offshore tax credit. “And I think that really poises the industry for significant growth.”

She added that the ITC is less risky for financiers than the production tax credit used to finance onshore wind because “we’re taking a tax credit on the upfront fair market value as opposed to the ongoing [power] production.”

But even with that, offshore developers will need multiple investors because some of the projects will need as much as $1 billion in financing, she added.

Handling all of the power generated by offshore wind — the Biden administration has set an offshore target of 30 GW by 2030, or 1,000 times the current offshore capacity of 30 MW, at a cost of about $12 billion/year — poses a related capital expenditure question: How much will be spent on transmission upgrades?

Transmission and interconnection infrastructure is a challenging problem for the industry as a whole, not just for offshore wind, said Huffman, briefly stepping out of his role as the moderator.

“We all, I think, expect this to become, in relatively short order, a major constraint on the construction of offshore wind plants. How do we deal with it? What are we going to need to do in order to address this constraint?” he asked.

Major investments will be happening, said Joao Metelo, former CEO of Principle Power, a California-based global offshore wind company that has developed a floating foundation for deeper waters, such as those off the West Coast.

“We are already seeing big announcements from the administration to push transmission, both small projects and HVDC projects,” Metelo said. “This need is widespread across the country, and it certainly affects offshore wind and onshore wind, and solar as well.

“I think there’s going to have to be … integrated transmission planning, both onshore and offshore projects. We already saw [a request for information] from New Jersey,” he said.

The webinar opened with remarks from U.S. Rep. Jerry McNerney (D-Calif.), a long-time wind energy supporter who set the tone of the discussion by noting that offshore wind poses “huge engineering challenges.”