DENVER — State regulators must change their thinking about the value of energy efficiency if their jurisdictions are to meet their net-zero-carbon goals, speakers told the National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners’ Summer Policy Summit.

“The way that we regulate utility energy-efficiency programs from my perspective is becoming increasingly out of synch with state policy and what the real driver of EE programs is and should be,” Paul Hibbard, a principal with Analysis Group and a former Massachusetts regulator, said during a panel discussion Sunday. To reduce carbon emissions “the first thing we should be doing to the maximum extent possible is … energy efficiency to a level that … goes way beyond what’s commonly implemented by electric utilities and gas utilities in the country today.”

Hibbard and Charlie Buck, director of regulatory affairs and market development for Oracle (NYSE:ORCL), said regulators should value EE by translating energy savings into carbon reductions using the social cost of carbon.

Avoided energy costs and ratepayer benefits do not equal the value of carbon abatement for states, they said, citing one of the conclusions Analysis Group made in a report it produced for Oracle last year.

“There are certain places where there are arbitrary caps on behavioral efficiency savings,” said Buck, whose company’s Opower unit helps customers reduce energy use through home energy reports, behavioral load shaping and proactive alerts. “I think those efforts are well intended, but at the same time, really what we should be going after is all cost-effective energy efficiency” as measured against other carbon-reduction efforts.

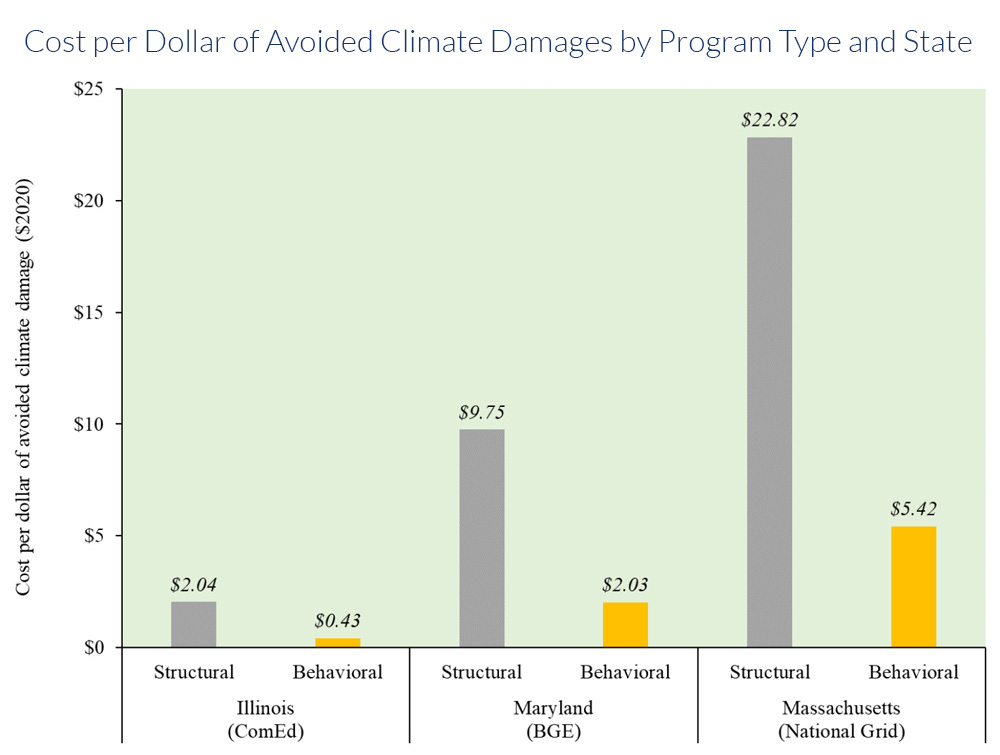

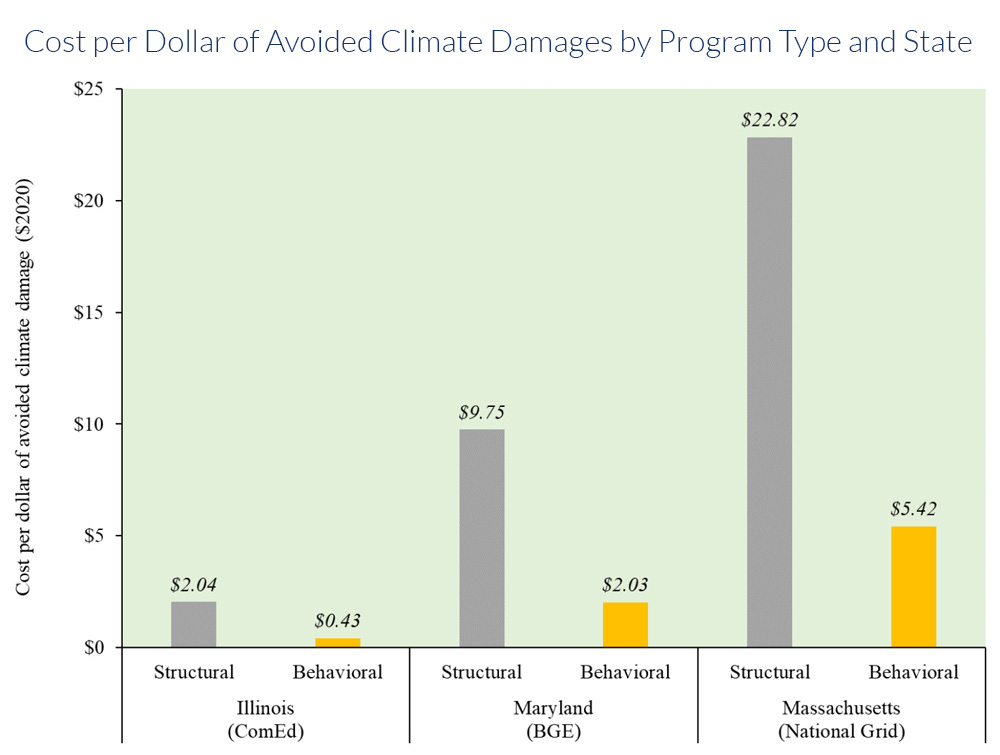

The report compared the cost and impact of structural energy efficiency (SEE) programs, which can require expensive investments out of reach for low- and moderate-income (LMI) residents, with behavioral energy efficiency (BEE) programs, which are free or cheap to implement.

SEE programs, which generally begin with a home energy audit and require the installation or retrofit of HVAC and other systems, can generate savings for up to 30 years.

BEE programs, which seek to change customer behavior by providing information on energy use and social norming (e.g., comparing one household’s energy use to their neighbors), typically produce savings over a shorter time frame but achieve them more quickly. Buck said behavioral programs can reduce customers’ electric usage by 1 to 2.5%, with smaller reductions for gas customers.

Analysis Group concluded that BEE programs can reduce greenhouse gas emissions faster than SEE programs and at only one-fifth the cost.

And because electricity generation is shifting to less carbon-intensive fuels, reducing electricity usage today avoids more emissions than reducing the same amount in the future, reducing the risk that the climate system will cross dangerous “tipping points.” That means EE programs initiated now will have a higher net present value than those deployed five years from now.

Analysis Group concluded that within six years, National Grid’s BEE program in Massachusetts could achieve the cumulative avoided damages that would take the utility’s SEE program almost 20 years.

One of the advantages of BEE programs is that they automatically enroll customers to receive home energy reports, while SEE programs require a customer to take several affirmative steps (e.g., choosing to participate based on a bill insert, selecting a contractor, selecting and purchasing energy-efficient equipment, etc.). As a result, BEE programs reach more than 10 times as many customers as SEE programs, the research shows.

The report found that BEE programs also complement SEE programs, resulting in higher enrollment in the latter.

BEE “is a great gateway drug to demand-side management,” Buck said. “Of course, customers can opt out if they want — but only 1 to 1.5% of customers ever do. And in so doing, you cannot only reach up to 60% of a utility’s service territory with these communications, you can also be very targeted to those low- to moderate-income, those harder-to-reach, market segments.”

LMI consumers save at the same rate as high-income consumers, according to the research. As a result, “energy efficiency stands out among all of the potential ways to decarbonize … that’s consistent with a lot of the states’ equity objectives,” Hibbard said.

While many states have cost caps on their EE programs, five states that invest in the maximum feasible amount of EE — Massachusetts, California, Rhode Island, Vermont and Connecticut — ranked among the top seven states in the 2019 American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy’s energy-efficiency ratings, Analysis Group said.

Karen Olesky, a staffer with the Nevada Public Utilities Commission who moderated the panel, asked Buck about the potential of BEE programs to grow.

“Had I been sitting here seven, eight years ago when I first joined Opower … I would have had a very different response. It’s been incredibly encouraging in that time to actually see the program grow — just exponentially,” he said. “There were programs when I came up in Southern California that were reaching 75,000 customers at a giant utility. They’re now reaching 2.8 million customers. So we are getting there. We’re starting to get there.”