The historic shift away from carbon-based fuels to clean energy sources such as solar — which the industry now asserts can supply 30% of the nation’s electricity by 2030 — is encountering significant resistance from some unexpected corners.

Whether they’re farmers, Native Americans or residents living in economically depressed neighborhoods, people who will live near utility-scale solar arrays are increasingly opposed.

The issue received a brief airing Wednesday in a virtual panel during the North American Smart Energy Week sponsored by Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA) and the Smart Electric Power Alliance.

“This session on land use is very timely, as we see more solar being developed and installed in more places. We are seeing more and a wider variety of land use conflicts,” said Sean Gallagher, vice president of state and regulatory affairs for SEIA, and moderator of the discussion.

Citing a Department of Energy study, Gallagher said the industry could supply 45% of the nation’s electricity using just 0.5% of the land in the lower 48 states by 2035. He stressed that equity and environmental issues must be considered in the planning process of any new solar development.

Chris Carr, an attorney focused on infrastructure development at a San Francisco law firm Paul Hastings LLP, said enhanced tribal consultation and environmental justice policies at both federal and state levels are now integral to any solar project developed in California and other Western states. Climate change and the impact of that on protected species are also significant considerations included in winning approval for solar projects, he said.

NIMBY

Representatives from two solar developers related new “not in my backyard” (NIMBY) issues their companies are encountering.

Jessica Robertson, director of policy and business development for Borrego Solar Systems, addressed resistance her company has encountered in Massachusetts.

“Massachusetts has the classic New England problem of really small parcels and small municipalities. They all have different zoning regulations and permitting processes and so that is definitely a challenge. But we also have rampant NIMBY-ism from people who are accustomed to their view being a certain way and they don’t want that to change,” Robertson said.

“And then we also have a very organized conservation movement, which normally I am fully on board with and really want to partner with in many, many ways. But there’s sometimes a really black-and-white view of land use, and the idea of cutting down a single tree in order for solar [development] becomes a nonstarter,” she said.

Robertson said a new state distributed generation incentive program that factors current land use when calculating a state incentive for a particular project has made solar development much more difficult if not impossible. “I think there’s a need to have a little bit more of a nuanced conversation about costs and benefits,” she concluded.

From a social justice point of view, Robertson reasoned that renewable energy has flipped the scenario from the past when power plants were built in regions distant from neighborhoods where the power would be used.

“I think we need to be upfront about that conversation and acknowledge that certain communities have really borne the brunt of our energy system for a really long time, and it’s time to spread that burden around a little bit more broadly and at the same time recognize that it’s a very different burden and shouldn’t hopefully be quite so big a deal as trying to locate a new coal plant,” she said.

Tyler Kanczuzewski, vice president of sustainability and marketing with Ind.-based Inovateus Solar, said NIMBY-ism and concerns about losing farmland are issues he encounters.

Regarding the first issue, Kanczuzewski said he has encountered rural residents who are accustomed to looking out at farmland with a first cup of coffee and just “don’t want to stare at a big solar array.” That issue is stronger for them than switching some land from farming crops to solar, he said. But there are real concerns among others about losing farmland.

“I think there is a little bit of uncertainty with some of the farm communities. They’re potentially losing potential crops to solar. They’re farming solar renewable energy instead of crops, and as you can tell, a lot of them are interested, but they’re a little bit insecure about the future.

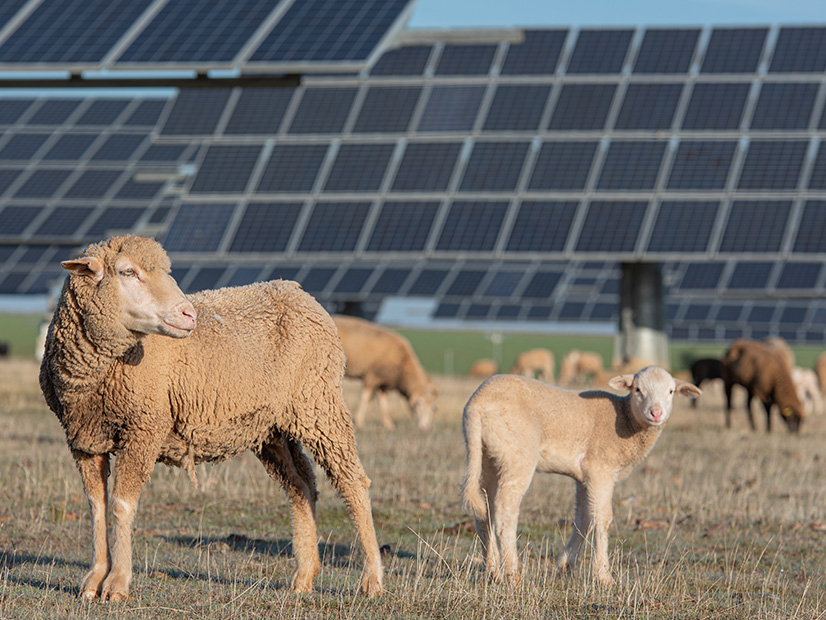

“But the good thing is that we’re learning that you can do things like [include a] pollinator habitat with the solar arrays and actually improve the soil health,” he said, in reference to planting regional wildflowers and in some cases regional grasses for sheep to graze in between the rows of solar arrays.

The plantings “help with water management, become a habitat for birds, bees and other species, and improve the soil health. And let’s say 20 or 25 years down the road when you decommission that solar array, you can actually have better soil there and you can farm on it again.

Kanczuzewski said the pollinator habitat movement is “gaining traction” in the Midwest, and particularly in Randolph County, Ind., where Inovateus is based.

“The county did a solar energy ordinance that includes pollinator friendly provision, so that was exciting for the state of Indiana, and more counties are doing that, I think, across the Midwest,” he said.

Who Benefits?

Colette Pichon Battle, founder and executive director of the Gulf Coast Center for Law & Policy, addressed environmental, equity and social justice involved when solar developers arrive in a neighborhood or region.

Battle said the development and siting of any industrial project, including a large solar project, comes down to democracy itself.

The idea of “some people having more gravity and value than others in these decisions is really a question about our democracy,” she said. “We have many processes that are supposed to be rooted in democracy that [instead] are leaning toward those who have privilege and access and the ability to challenge power.”

Regarding brownfield sites and environmental justice spaces, Battle noted, “We have to be careful that finding the cheapest, most available land does not give to black and brown and poor communities what privileged … communities don’t want.

“The truth is that these things benefit everybody, including the planet, so we need to scale this renewable energy up. For that reason, not because those victims over there really need our help. But because the planet is in trouble and we need to shift our entire infrastructure,” she said.

Battle said she agreed with Robertson’s notion of having “nuanced” conversations, “We have to have those kinds of conversations, and we have to shift this narrative around who’s benefiting.”

“I think the narrative of the benefit has to be a much more collective one around what the transformation required to address this climate crisis is really calling all of us to do and to bear equally as much as possible.”