By 2035, zero-emission medium- and heavy-duty vehicles (MHDVs) — from delivery vans to 18-wheelers — should be no more expensive to buy and operate than those that run on diesel, according to a new study from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL).

With that kind of price parity on the horizon, electric trucks could make up 42% of new MHDV sales by 2030 and close to 100% by 2045, the report says.

Those timelines map out “a clear pathway for trucking companies to make the switch from diesel to electric that will help them cut costs and pollution for their customers, while combating climate change,” Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm said in the March 7 press release announcing the study.

Based on 2019 figures, MHDVs produce about 445 million metric tons of carbon dioxide per year, 21% of the U.S. transportation sector’s total emissions, the report says. While California and other states are attempting to reduce those emissions with rules requiring that increasing percentages of new truck sales be electric, the NREL report builds on the assumption that adoption of these zero-emission vehicles (ZEVs) will be driven by economics by comparing total cost of ownership (TCO).

A key metric for fleet owners and drivers, TCO includes not only the upfront costs to buy a vehicle, but also its fuel, maintenance and resale value. The report plots the time frames for when battery electric or fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) will reach price parity with comparable diesel vehicles.

The upfront purchase price for an electric MHDV is generally higher than a traditional diesel-powered vehicle with an internal combustion engine (ICE) at present, while fuel and maintenance costs are lower. A 2021 study from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory estimated maintenance for a heavy-duty diesel truck at $12,000 to $13,000 per year versus $6,500 per year for a comparable electric truck.

The NREL report projects that battery and fuel cell prices will trend down between 2035 and 2050, which will lower the overall costs for electric MHDVs.

Electric trucks may be two to three times more expensive than ICE vehicles, according to Fred Ligouri, a spokesperson for Daimler Trucks North America. The company’s Freightliner division has been working with customers to test out a small, preproduction fleet of electric MHDVs and will begin production on its heavy-duty model in late 2022, he said.

Drive More, Save More

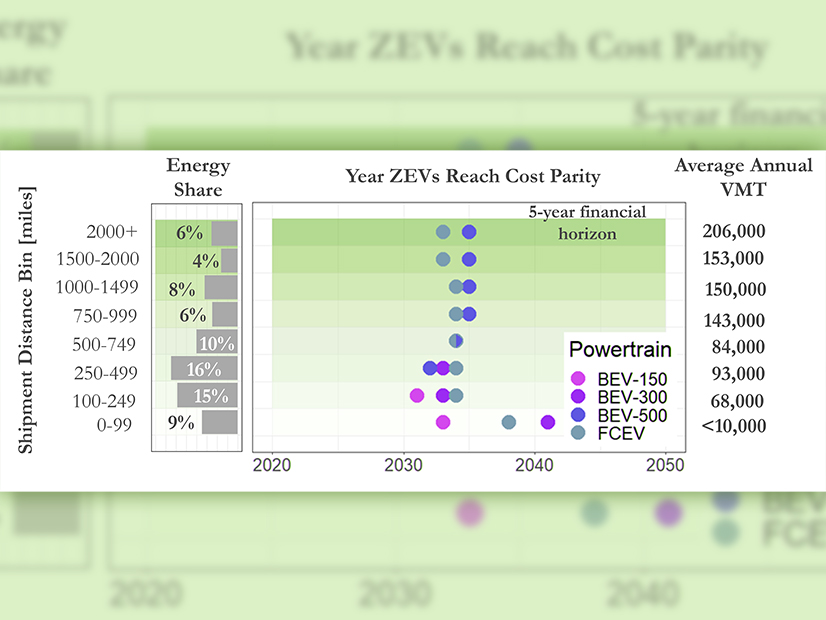

The timelines for when ZEVs ― both battery electric vehicles and FCEVs ― will reach price parity with ICE vehicles depends on the vehicle type — medium or heavy duty — and the distances they travel.

For example, the study finds that a heavy-duty battery electric truck with a range of 300 miles and traveling 100 to 500 miles per trip will reach price parity with a similar diesel vehicle around 2033. But if the truck is used for shorter trips, the break-even point is pushed back to 2041.

The correlation between these short distances and later break-even points holds true across different classes. “It’s not a technical problem; it’s mostly a matter of cost,” said Matteo Muratori, team leader for integrated transportation and energy systems analysis at NREL.

With EVs, “you spend more money when you buy the vehicle, but the more you drive it, the more money you save,” Muratori said in an interview with NetZero Insider. “Vehicles that are driven more save more and reduce emissions more; vehicles driven less save less. It takes longer to recover the initial capital cost.”

At the same time, he said, range matters; an electric truck with a range of 150 miles could reach price parity sooner than one with a range of 300 to 500 miles. “Shorter-range vehicles make more economic sense in the near term, and the longer-range vehicles start making economic sense when you get closer to 2030 or 2035,” he said.

Price parity for FCEVs also varies. For medium-duty vehicles, price parity with diesel is expected in 2031, while for heavy-duty FCEVs, the break-even point comes in 2033 or 2034.

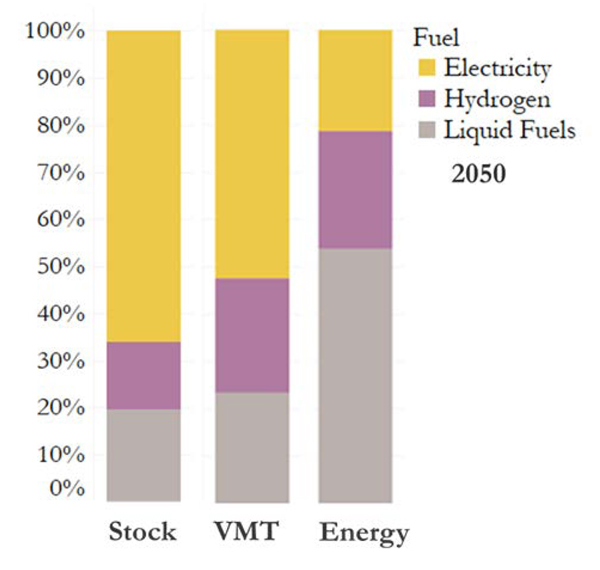

Based on these projections, the report estimates that by 2045, 80% of all medium- and heavy-duty trucks on the road could be ZEVs, cutting emissions 69% from 2019 levels.

The report also notes that electric buses have become the leading edge in this transition, as they are already cost-competitive with diesel vehicles “in certain contexts … depending on vehicle and fuel prices and driving requirements.” The TCO for battery electric buses is anticipated to be “well below” that of diesel buses by 2032, the report says.

The Caveats

The NREL report comes with caveats, the most significant of which is the volatile nature of diesel prices. With the war in Ukraine and ban on Russian oil imports driving record spikes in prices, ZEVs could attract a wider range of buyers.

“Diesel is never the cheapest solution anymore because it is priced higher,” Muratori said.

Megawatt chargers will also be needed to keep EVs competitive, he said, and in some instances, FCEVs may be more time- and cost-efficient than battery electric vehicles because fuel cells run on hydrogen, which allows quicker refueling.

“If hydrogen is really cheap and electricity is really expensive, fuel cell vehicles make a lot more sense and vice versa,” Muratori said.

The report’s focus on bottom-line economics also leaves out key variables that may affect the speed and scope of electric truck adoption, such as the time and cost of building out the charging and refueling networks and the supply chains that will be needed to transition the U.S. MHDV fleet. The potential impact of increasingly rigorous federal and state emission reduction and fuel efficiency standards are also not discussed.

For example, California’s clean truck rules have been adopted by five other states: Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Oregon and Washington. The rules require that 55% of light-duty truck sales be ZEVs by 2035; for MHD trucks, the requirement is 75% by 2035, goals that will likely affect adoption rates and market growth in those states.

Muratori said the impacts of infrastructure, supply chain and regulatory issues will be important to track as the market evolves. But echoing the report, he argues that economics will drive ZEV adoption in the commercial truck and freight sectors, and demand could rise quickly once cost parity is reached.

More IIJA Funds

Underlining to the feasibility of widespread adoption of electric MHDVs, the NREL report was released alongside a series of White House announcements intended “to advance clean heavy-duty vehicles, as part of our electric, zero-emissions transportation future,” according to a March 7 fact sheet.

While not directly related to price parity, EPA’s new proposed regulations to cut tailpipe emissions of nitrogen oxides from heavy-duty trucks were framed as a stimulus to “jump-start the transition to zero-emission vehicles in the heavy-duty fleet,” the fact sheet said. The target for 2045 is a 60% emissions reduction.

The proposed regulations would also set stricter standards for greenhouse gas emissions for trucking sectors that are already seeing faster adoption of EVs, such as school and public transit buses and commercial delivery trucks.

Other funding announcements rolled out with the NREL report include $17 million from EPA for electric buses to replace diesel vehicles in underserved communities, and $450 million from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) for projects that will cut greenhouse gas emissions at U.S. ports.

The White House continued to push forward on heavy-duty vehicle electrification with Monday’s announcement of another round of grants for 70 projects to improve and electrify public transportation in 39 states. The $409.3 million in funding from the IIJA will be used to “modernize and electrify America’s buses, make bus systems and routes more reliable, and improve their safety,” according to a Department of Transportation press release.

“These grants will help people in communities large and small get to work, get to school, and access the services they need,” Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg said in the release. “Everyone deserves access to safe, reliable, clean public transportation.”

Among the grantees, the Connecticut Department of Transportation is getting $11.4 million to buy electric buses, while the Regional Transportation Commission of Southern Nevada will receive close to $5 million for new hydrogen fuel cell buses, according to the release. Still more projects will be funded over the next five years with $5.1 billion in IIJA dollars, the release said.