A New Jersey Board of Public Utilities (BPU) study into the contentious question of how much ratepayers will end up paying in 2030 for the state’s transition to clean energy faces a multitude of concerns from opponents and supporters who fear the proposed study will miss key costs and benefits.

More than two dozen speakers offered suggested improvements at a three-and-a-half-hour online public hearing Friday at which the BPU’s consultant, The Brattle Group, laid out the framework for the study and sought public input on its design and input assumptions — to little commendation from speakers and a wealth of criticism.

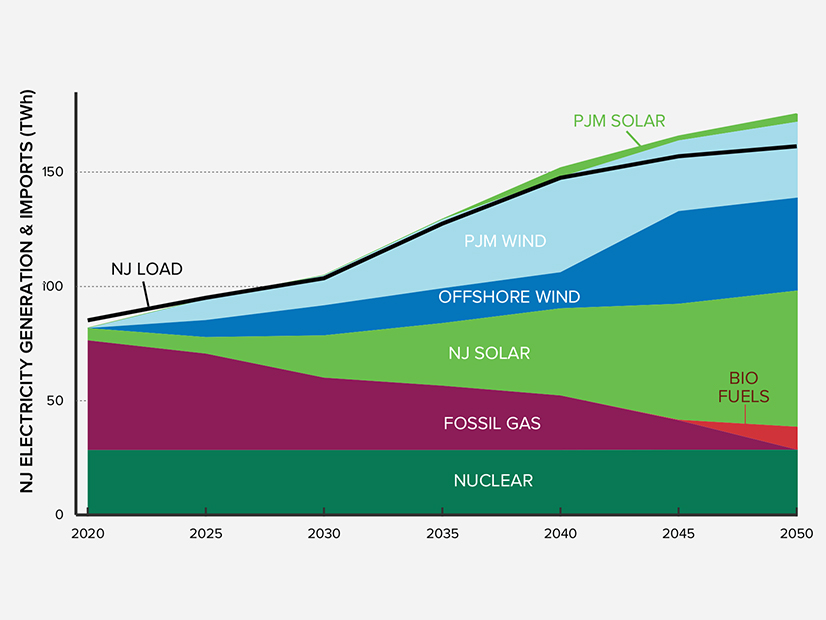

The study is designed to evaluate the cost to ratepayers in 2030 if the state implements the policies in its 2019 Energy Master Plan (EMP). The plan calls for the state to reach 100% clean energy by 2050, mainly by improving energy efficiency and shifting to clean energy generation, mainly wind and solar. (See Lawmakers Back Putting NJ’s Clean Energy Plan into Law.)

Supporters of the plan argued at the hearing that a focus only on the cost to ratepayers would be too narrow and leave important costs uncounted. Missing from the assessment, speakers argued, would be the expected, massive costs that would result from not addressing climate change and coping with storms, excessive wind, flooding and other natural disasters. Also unaddressed would be the impact to resident health resulting from failing to cut emissions, speakers said.

“The bottom line here is you need to change your goals for this study,” said Ken Dolsky, a steering committee member for Empower New Jersey, a coalition of more than 120 environmental, citizen, faith and progressive groups.

“The goal of the EMP is to significantly reduce greenhouse gases in order to avoid or reduce the impacts of climate change, not just ratepayer cost of energy,” he said. “Therefore, if you’re addressing the EMP, this cost analysis must include some portion, if not all, of the total expected costs of climate change in New Jersey.”

From the opposite direction, the Chamber of Commerce Southern New Jersey argued that the study would miss key costs, especially the expense to property owners and businesses required to meet the plan’s demand to switch from natural gas to electricity for furnaces, hot water boilers, transportation and in other areas.

Hilary Chebra, a lobbyist for the chamber, said the study, as outlined by Brattle, “falls short” in giving the business community “a more comprehensive assessment of the actual cost associated with implementing the EMP.”

“Energy costs impact competitiveness, and they’re a key factor in a business’s decision on locations and their profitability,” she said. “So, the costs of the EMP that are real expenses to the business community — that they will have to incur with the implementation — should be really thoroughly examined.”

Rate Impacts and Energy Burden

Murphy, a Democrat who instigated the EMP, wants the state to cut greenhouse gas emission levels to 80% below 2006 levels by 2050. The governor’s initiatives to help reach that goal include: a major offshore wind program that aims to generate 7.5 GW of electricity by 2035; reshaping the state’s solar incentives; introducing new rules to curb emissions from building heating and hot water systems; and developing a raft of programs aiming to get more electric vehicle chargers installed around the state and more EVs on the road.

Business groups, and some Republicans, have long expressed concern about the cost of the shift to low-emission energy sources, especially the focus on electrification as opposed to other clean energy alternatives, such as hydrogen and low-emission natural gas. In response, the BPU in May approved the hiring of Brattle to study the cost. The BPU expects to release the final report in the second or third quarter of this year.

The study is “is aimed at understanding the impact of the EMP on customers’ energy bills through a comprehensive analysis of rate impacts and overall energy burden as of 2030,” according to the BPU announcement of the hearing.

“The first question is, let’s just figure out the total costs of implementing these programs as of 2030,” Sanem Sergici, a Brattle principal, told the hearing. “Then, we will quantify the economic benefits and savings to the customers because, as I mentioned, these programs will lead to potentially reduced gasoline expenses [and] reduced natural gas usage.”

The study, according to the BPU, will look at:

- the gross costs in 2030 of implementing the plan;

- reductions in energy consumption driven by increased efficiency;

- shifts in energy consumption in heating and transportation toward increased electricity usage;

- changes to electricity and natural gas rates as costs are applied across changing electricity and gas volumes; and

- shifts in energy burden from gasoline toward electricity consumption, alongside advances in EV adoption and heating electrification.

Brattle said it will use three scenarios: a continuation of the state’s current energy strategy; the pathway advocated by the EMP to reach 100% clean energy by 2050; and an “ambitious pathway” of reaching 100% clean energy by 2035.

The study will also look at the economic benefits and savings to consumers as a result of reduced gasoline, natural gas and electricity consumption, according to the BPU. And it will show the impact of the three policy scenarios on net consumer costs, in the form of total energy bills, and on different customer segments, such as low-income consumers.

Shaping the Study

Barbara Blumenthal, clean energy policy consultant for the New Jersey Conservation Foundation, said that by looking at the impact in 2030, the study would catch all the costs but not all the benefits because they take longer to develop.

“The investments come first, and the benefits in terms of emissions reductions in the health impacts and all of the other economic benefits lag,” she said. “So, it’s a little odd to cut off a study in 2030 after a period of investment, where the actual benefits in terms of emissions reductions are not yet cumulatively very significant.”

The New Jersey Division of Rate Counsel, however, said the study should focus on the costs to ratepayers, especially the impact on low-income ratepayers who could struggle to pay any increases.

“Rate Counsel believes that the focus of this analysis should be costs,” Sarah Steindel, assistant deputy rate counsel, told the hearing. “To the extent benefits are addressed, they need to be reported separately so that the board and the public can clearly see the cost customers will be paying. Any analysis of the benefits, like the analysis of costs, should consider how they are allocated among different ratepayer segments, including low-income ratepayers.”

Dolksy, of Empower New Jersey, expressed concern that the study as planned would fail to take into account the cost that would not be incurred as a result of the state pursuing a carbon-free policy. He cited the examples of treatment for people suffering from the effects of air pollution, increased health insurance costs and the loss of employment productivity from “people [who] cannot work because they’re sick due to related heat and unhealthy air effects.”

Tracy Carluccio, deputy director of the Delaware Riverkeeper Network, urged the BPU to expand the scope of the study.

“While we understand the significance of BPU assessing the effects to ratepayers of policy changes that address climate change, the assessment must be performed in the context of the impacts to the human and natural world,” she said. “And these costs must be considered in the study. This context is a world of disasters that will cause increasing damage, health harms, economic hardship and loss of life if we do too little too late.”

Chebra, of the Chamber of Commerce, said the proposed study would not catch the expenses to businesses such as the plan’s call to cut energy consumption and emissions in buildings. She questioned whether, for example, the study would reflect the thousands of dollars it would cost a building owner or manager to switch from a natural gas furnace to an electric heat pump.

Another concern, she said, is whether the study’s estimate of the costs of pursuing clean energy would include the amount spent to modernize the grid to handle the heightened volume of electricity flowing through the system. The BPU is at present soliciting proposals on how to implement that upgrade. (See Fierce Competition in Plans to Upgrade NJ Grid.)

“That is, again, a cost that ratepayers will have to bear,” she said.