Two new reports released Wednesday document the progress and challenges in the global effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

DNV issued the 2023 edition of its Energy Transition Outlook, concluding that the transition is still at the starting line, with new renewable generating capacity growing at the same rate as demand.

The outlook is not sunny — the report projects global warming well beyond the 2100 target of 1.5 degrees Celsius — but there are some points of optimism: It predicts slight reductions of emissions starting as soon as next year and dropping 4% lower by 2030. It predicts a 46% reduction in emissions by 2050, when it expects non-fossil energy to supply 52% of world demand.

The Energy Information Administration covers some of the same ground in its annual International Energy Outlook.

The two reports are not directly comparable, as EIA extrapolates future models from an unchanging 2023 policy baseline. It projects global fossil fuel consumption and carbon dioxide emissions would rise through 2050 without major policy adjustments to the current trajectory.

DNV Outlook

An introductory message from DNV Group President Remi Eriksen begins with a simple assessment: “If ‘energy transition’ means clean energy replaces fossil fuel in absolute terms, then the transition has not truly started.”

High prices have had opposite effects on energy industry sectors, making oil and gas exploration more lucrative and complicating the buildout of renewables, he said.

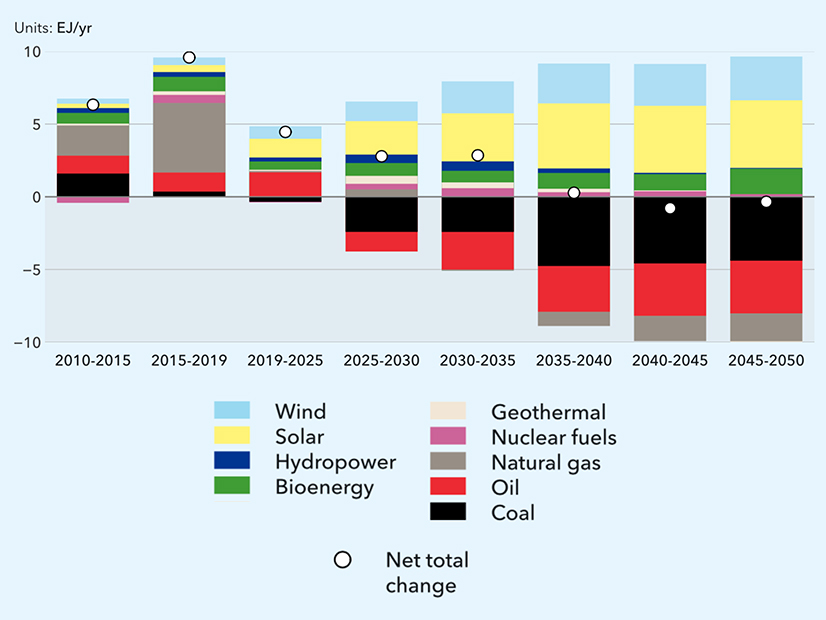

But DNV projects that emissions from oil will peak in 2025 and from natural gas in 2027.

Policy changes already are showing results in the US and EU, where per-capita greenhouse gas emissions are among the highest in the world, it said. However, in the next decade, transmission constraints and supply chain shortfalls pose a threat to progress.

Another trend playing out now is the rise of oil and natural gas prices, which tarnished the status of gas as a bridge fuel during the transition and prompted an increase in coal-fired generation in several countries. But increased fossil use in lower-income countries is gradually balanced over the next decade by increased renewables in wealthier countries, DNV projects.

Advanced economies will drive development of the technologies that will help to enable the transition, but that will not bring as much benefit to medium- and low-income regions, which need de-risked funding to accelerate the transition.

Overall, the energy mix is projected to transition from 80%/20% fossil-renewable in 2023 to 48/52 renewable by 2050, with a 10-fold increase in wind generation and 17-fold increase in solar power.

Energy security has become a motivating factor since Russia invaded Ukraine, disrupting energy supplies and prices. Local energy production is now a priority in many countries, whether it be renewable, nuclear or coal.

So while progress is being made, DNV concludes, it is not being made fast enough. Global emissions would need to be cut 50% by 2030 to achieve a net-zero energy system by 2050, but the report does not project a 50% emission reduction even by 2050.

The global target held out by some activists and scientists — keep the planet from warming more than 1.5 C by 2100 — keeps getting harder to reach, DNV said. It calculates a 2.2-degree increase through 2100 under the emissions forecast in the outlook.

EIA Outlook

EIA said its projections in the IEA conclude that while zero-carbon technology such as renewables and nuclear would meet the bulk of new demand through 2050, that is not enough to counter the increase in other sources of CO2 emissions. These include global population growth, increased regional manufacturing and the push for higher standards of living.

The projections are not forecasts, nor are they even likely scenarios; they assume the policies in place as of late 2022/early 2023 will remain unchanged for the next 27 years. (In fact, the authors note, some policy changes already have occurred as of late 2023.) Rather, the projections are a policy-neutral baseline against which future policy decisions can be considered, the report says.

EIA highlighted three main takeaways from the report.

All cases modeled show global energy consumption rising, with the fastest growth coming in the residential and industrial sectors and the greatest increase in use of liquid fuels coming in industrial applications. As more electric vehicles hit the road, applications such as chemical production account for a greater share of the liquid fuels used.

Global electric generation capacity grows anywhere from 55 to 108% from 2022 to 2050, depending on the case modeled, and actual electricity generated rises 30 to 76%. Renewables, nuclear and battery storage account for most of the increase in both metrics, but renewables grow fastest in cases that assume high economic growth and greater electricity demand.

Energy security is a driving concern in both directions: It hastens the transition away from fossil fuels in some countries and prompts increased fossil consumption in others.

“IEO2023 fills an important niche among global outlooks by focusing on a plausible but sober assessment of global energy trends through the first half of the century,” EIA Administrator Joe DeCarolis said in a news release. “There is considerable uncertainty in the energy landscape over the next 30 years, and the IEO provides a set of policy-neutral baselines that will help guide sound decision-making.”