After scrapping most Trudeau-era climate policies, Prime Minister Mark Carney hopes to tighten rules over Canada’s industrial carbon markets, which observers say have failed to incentivize emission reductions.

Since replacing Justin Trudeau in March 2025, Carney has eliminated a controversial carbon tax on consumer fuels, suspended a requirement that electric vehicles make up an increasing share of car sales and backed off on a phaseout of gas-fired generating plants.

As a result, the nation’s emissions trajectory is largely dependent on industrial carbon markets created under federal legislation in 2018 and now the subject of a scheduled review.

The Ministry of Environment and Climate Change in December issued a discussion paper seeking feedback on the federal “benchmark” — the national stringency standard all provincial and territorial systems must meet — which covers more than one-third of Canada’s total emissions, including the oil and gas industry and electric generation.

The government said its engagement seeks to ensure that industrial pricing “provides the necessary incentives and framework to drive decarbonization, clean technology investment and competitiveness.” Comments are due Jan. 30 via email to tarificationducarbone-carbonpricing@ec.gc.ca.

Alberta Agreement

The discussion paper acknowledges complaints by industry that the existing system is inefficient and is hurting their competitiveness. It also follows Carney’s Nov. 27 Memorandum of Understanding with Alberta Premier Danielle Smith, in which the federal government made numerous climate concessions, including the suspension of federal Clean Electricity Regulations, which would have required provinces to start phasing out gas-powered generating plants lacking carbon capture in 2035.

Although the electricity rules are being lifted only in Alberta — the nation’s largest greenhouse gas emitter — it “surely opens the door to doing likewise for other provinces that have chafed at it,” wrote Globe and Mail columnist Adam Radwanski.

The concessions prompted Steven Guilbeault — formerly Trudeau’s environment minister — to resign from Carney’s Liberal cabinet. But some climate activists said they were cheered by Alberta’s agreement to work with the federal government to raise the price of credits in the province’s oversupplied industrial carbon market — now trading below $20/metric ton (Mt) — to a “headline” price of $130/Mt.

Facilities with compliance obligations must pay the headline price or submit credits. A $130/Mt headline price would create incentives for heavy emitters to invest in climate capture and other green technologies, said Michael Bernstein, CEO of climate policy group Clean Prosperity.

“This agreement is a sign that we could finally be moving beyond the long-running disagreements between Ottawa and the provinces over climate policy, and charting a pragmatic path to achieve our climate goals while also strengthening Canada’s economy,” he said.

To submit a commentary on this topic, email forum@rtoinsider.com.

Provinces Falling Short

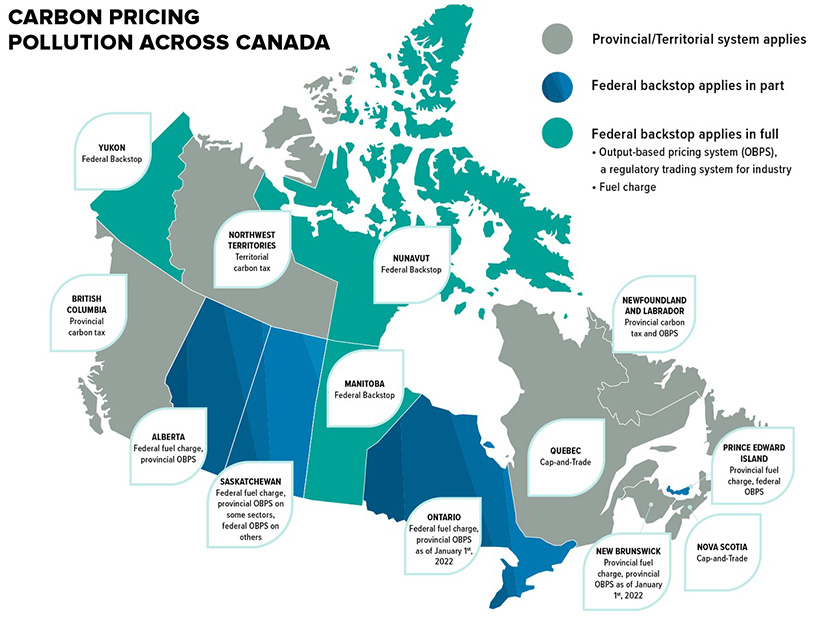

Seven of Canada’s provinces, including Alberta and Ontario, use provincial output-based pricing systems (OBPS), while four use a similar federal system.

OBPS set performance standards defined as emissions per unit of production. Companies whose production is better than the standard generate credits they can sell; those that cannot meet the standard either buy credits or pay the headline carbon price on excess emissions.

Designed correctly, says the Canadian Climate Institute, such systems can incentivize emission reductions with low overall costs and little incentive to shift production to jurisdictions without carbon limits.

But the institute and others say some current markets are not working because they are oversupplied with credits. While the 2025 headline price was $95/Mt — scheduled to rise to $170/Mt in 2030 — emitters can purchase credits at a fraction of that cost in Alberta and elsewhere.

Clear Blue Markets, which provides consulting and market research on carbon markets, said provincial markets are falling short, citing a lack of price transparency, Alberta’s freeze on its carbon price and oversupply risks in British Columbia and Quebec.

Alberta’s freezing of its headline price and its surplus of 48 million credits have pushed trading prices to about $18/Mt, the consulting firm said in late November. Prices in federal OBPS, including Manitoba and Prince Edward Island, have been depressed to $37.50 by the inflow of cheap “offsets” from Alberta, it said.

“Ontario’s [Emissions Performance Standards program] remains robust, supporting a strong credit market. However, its 2024 funding mechanism, tying proceeds to emissions paid rather than performance, may weaken the emissions reduction signal,” Clear Blue Markets said.

Climate advocates say the program also needs a financial mechanism to establish a price floor on credits, as would be established at $130/Mt under the MOU with Alberta.

“To turn this MOU into shovels in the ground, that financial mechanism should take the form of carbon contracts for difference offered jointly by the federal and Alberta governments,” Bernstein said. “These contracts are the insurance policy that will de-risk tens of billions in low-carbon investment by giving investors confidence in the durability of industrial carbon pricing.”

“If governments uphold their commitments to strong carbon markets, the contracts need never be exercised, and so cost nothing to taxpayers,” Clean Prosperity said.

Industry Complaints

In 2024, industry organizations including Canadian Manufacturers & Exporters, the Canadian Renewable Energy Association, the Canadian Steel Producers Association, the Cement Association of Canada and the Chemistry Industry Association of Canada sent an open letter to Canada’s provincial environment ministers complaining of a “disconnect” among the nation’s provincial and territorial carbon markets that they said was hurting economic growth and decarbonization.

The group said it supports industrial carbon markets as “the most flexible and cost-effective way to incentivize industry to systematically reduce emissions.”

But it said “a patchwork of provincial carbon pricing systems has produced numerous barriers and created significant red tape across efforts to decarbonize.”

The group called for more transparency in credit markets and for removing rules that prevent industry from buying and selling carbon credits across provincial borders.

It also asked for “high-integrity offset protocols” to ensure emissions reductions are “permanent, additional and verifiable” and that provinces should invest 100% of industrial carbon pricing revenues into industry to accelerate decarbonization.

It also sought actions to support vulnerable sectors and prevent carbon leakage to jurisdictions with less stringent climate policies, citing the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, a tariff on imports of carbon-intensive products such as steel, cement and electricity.

Costs

In a 2023 study on the impact of the carbon pricing on Ontario, the Canadian Energy Centre predicted it would increase costs almost 11.8% for the province’s electric generation, transmission and distribution sector.

The study said carbon pricing would fall most heavily on the province’s iron and steel manufacturing sector — with a 62% increase — due to its use of coke and coal. Basic chemicals, pesticides and fertilizers were projected to jump 29.5%.

“The carbon tax will have the most significant impact on those industries in the manufacturing sector that have a high trade exposure and a low profit margin,” said CEC. The group’s goal is to make Canada “the supplier of choice for the world’s growing demand for responsibly produced energy.”

Three Options

Existing mandatory carbon pricing systems are believed to cover 595 facilities and 252 Mt of CO2 annually (36% of Canada’s emissions). Including voluntary facilities, existing carbon pricing systems are estimated to cover 274-281 Mt of emissions (39-40%).

The ministry said it is considering three options for determining what emitters will be covered by carbon regulations: The “threshold-based” option would cover all industrial and manufacturing facilities emitting above 10,000 (Option 1A) or 25,000 Mt (Option 1B) annually (264-273 Mt; 38-39%).

Option 2, an “activity-based” approach, seeks to cover all facilities in an industry to avoid providing a competitive advantage to smaller facilities. The ministry proposed covering oil and gas, mining, chemicals, fertilizers and other manufacturing — including steel and cement — that emit at least 10,000 Mt annually (278 Mt; 40%).

Option 3, which combines the threshold- and activity-based approaches, would be the “most effective” at incentivizing emission reductions, the ministry said (284 Mt; 41%.)

All three options would apply to fossil-fueled electric generation.

The government’s engagement to improve carbon markets design and price signals means that “meeting the federal benchmark will increasingly require jurisdictions to demonstrate that their systems function as effective markets and not simply that they comply on paper,” said Sussex Capital. “While provinces and territories will retain flexibility over design, the federal government is signaling higher expectations around durable price signals, healthy credit markets and demonstrable investment impacts.”

The MOU requires Alberta and the federal government to reach an agreement on the $130/Mt price by April 1.

“How this shakes out could determine whether an agreement to work together on policy and potential pipeline approval scuppers Canadian climate action, or whether it evolves into a better, more broadly supported effort to combat global warming,” wrote the Toronto Star’s Alex Ballingall.