About 30 low- and moderate-income (LMI) Virginia households could soon have access to their own solar power, if a pilot project proposed by the Clean Energy States Alliance (CESA) comes to fruition.

Wafa May Elamin and Nate Hausman, project directors for CESA, presented the pilot plan to the Virginia Clean Energy Advisory Board (CEAB) on July 21. Third-party leases to last 25 years would likely be the best option for these LMI households, Hausman told Net Zero Insider after the meeting, but CESA is not officially recommending that, saying instead that there should be “an open-ended financing solicitation.”

“Market economics in Virginia make it difficult for residential solar projects for LMI households to pencil out,” Hausman said during the CEAB meeting. “A fundamental precept of the program would be to guarantee that the transactions are cashflow-positive for participating LMI households,” he said afterward. “If the program ends up being structured as a leasing arrangement, that means LMI customers would save more on their electricity bills, via bill credits, from hosting a solar system than they would incur in the way of monthly lease payments to the third-party system owner.”

Hausman told NetZero Insider that the goal under the 2019 state law creating the CEAB (HB 2741) is to supply solar energy to LMI residents. Battery storage “is not contemplated” for the pilot households, he said.

As of now, the budget for the pilot program consists of $200,000 in “repurposed” federal funds from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, enacted during President Barack Obama’s first term. CESA was also awarded an anonymous grant to provide a year of funding to help the Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy (DMME) and CEAB develop the pilot, Elamin said. The timeline is yet to be determined, but the program will be developed in 2022 if it goes ahead. “Our overall aim is to launch a successful pilot program that can be scaled, and that will help demonstrate the case for long-term program investment and expansion,” Elamin said.

“Our goal is to provide a strong foundation for a program that could be scaled up with additional funding,” Hausman said.

The July 21 meeting followed CESA’s presentation of background market research to CEAB in March, after which the board and DMME staff gave their feedback and CESA “expanded our pilot program selection variables and re-examined potential jurisdictions for a pilot,” Elamin said. “In conjunction with DMME, we conducted informational interviews with solar providers that offer residential solar leases in other state markets.”

The proposed 30-household pilot program would require about $6,500 in direct public subsidies per solar project, he said, which comes to another $195,000 on top of the initial pilot program financing budget of $200,000. If third-party leases are used, the developer will own the projects.

Solar Energy Only for the Rich?

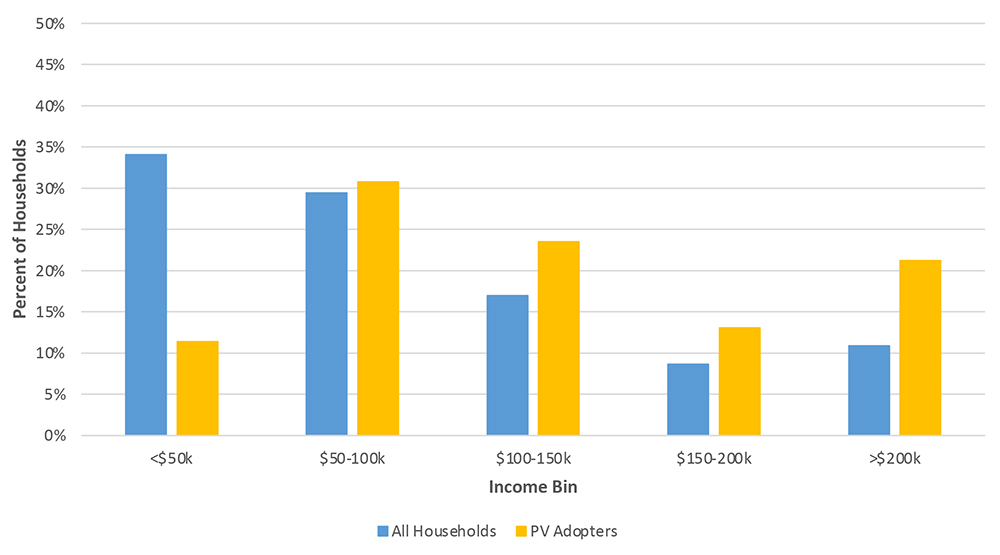

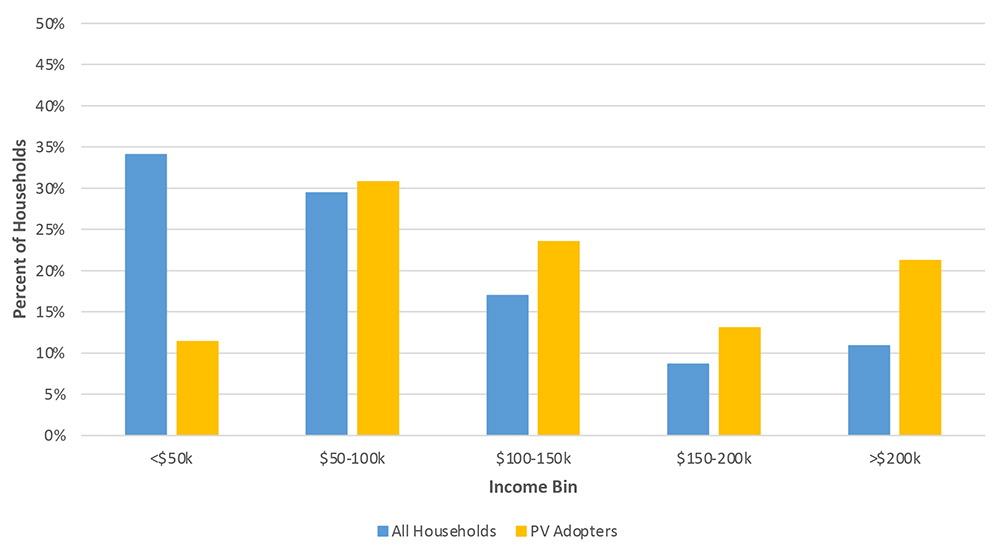

The subsidies are necessary because without them, upper-income Virginians are far likelier to go solar than LMI households. Analysis from CESA and the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory shows that Virginia households with 120% or more of the average median income made up 60% of all solar energy adopters in the state between 2010 and 2019, while those with less than 60% of the average made up just 10%.

“This has been static or even more tilted toward upper income in the last 10 years,” Hausman said. “If we care about solar equity, a market intervention may be in order.”

This is not a Virginia-specific problem. LMI households pay proportionally more of their income on energy, according to the U.S. Department of Energy. “According to DOE’s Low-Income Energy Affordability Data (LEAD) Tool, the national average energy burden for low-income households is 8.6%, three times higher than for non-low-income households, which is estimated at 3%,” the department website says. “In some areas, depending on location and income, energy burden can be as high as 30%. Of all U.S. households, 44%, or about 50 million, are defined as low-income.”

Hausman said CESA is suggesting the pilot project focus on “LMI single-family homeowners who have previously participated in weatherization services.” This is because “it’s written into the statute that there has to be prior energy efficiency” by participating households.

The DMME would competitively select solar companies and provide support and outreach assistance for them to reach two or three underserved markets with focused, inclusive and community-based marketing campaigns.

“The program guarantees that solar projects are structured with contracts that are cashflow-positive for LMI participants and have no hidden fees,” Hausman told the board. There would be direct oversight of participating solar companies.

“DMME, in conjunction with the Clean Energy Advisory Board, would provide direct oversight controls over participating solar companies,” Hausman told NetZero Insider. “Presumably, DMME would retain the right to withdraw solar providers from the pilot if program expectations were not met. CESA is also recommending that, based on mandates in state law, the program focus on families with 60% or less of the state median income for streamlined eligibility.”

The “top three potential locations” CESA has identified for the pilot program are Hopewell and Petersburg, both near the state capital of Richmond, and Wise County, in the far southwestern corner of the state, on the border with Kentucky. In Hopewell, the annual median household income in 2019 was $41,600, while the other two locales came in under $40,000 apiece.

At the end of the meeting, the CEAB voted unanimously to authorize the DMME to continue working with CESA on the pilot project. The next step will be for CESA and the CEAB’s Stakeholder Engagement and Marketing Committee to reach out to stakeholders in pilot jurisdictions, such as community organizations, weatherization service providers, local utilities, municipal officials, solar installers and affordable housing providers, to solicit input on program design and viability.

That would be followed by the drafting of a timeline for pilot program development, and then a solicitation for solar providers for the pilot.