Decarbonizing the maritime industry entails much more than switching ships to zero-emission fuel, leaders in the sector said Thursday.

It will require creating the green corridors envisioned in the Clydebank Declaration — linked mini-ecosystems with participation of shippers, their support industries, ports, governments and others — they told an audience at the Global Clean Energy Action Forum in Pittsburgh.

Two dozen nations signed the Clydebank Declaration formalizing the green corridor concept at COP26, the United Nations Climate Change Conference in 2021.

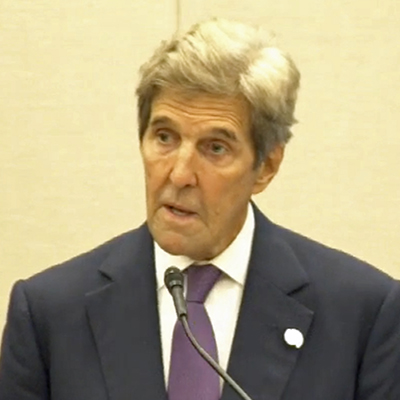

U.S. Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry discusses green shipping at the GCEAF in Pittsburgh, Pa., on Thursday, Sept. 22. | Global Clean Energy Action Forum

U.S. Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry discusses green shipping at the GCEAF in Pittsburgh, Pa., on Thursday, Sept. 22. | Global Clean Energy Action ForumYet emissions in the shipping sector are still rising — not the trajectory needed to comply with the Paris Agreement on climate change, said John Kerry, the U.S. special presidential envoy for climate.

“If shipping were a country, it would be the eighth largest emitter of greenhouse gases in the world,” he said.

It’s not enough to have steel mills, automobiles and power plants decarbonize, he added. “We’ve got to have shipping at the table, in a serious way. The green shipping challenge will encourage everyone up and down the entire food chain.”

The food chain extends beyond the fuel that runs the ship, all the way to details such as how the cranes in the port are powered, Kerry said. It is “a continuity of effort, so that the entire corridor, from start to finish, becomes green.”

Rikke Wetter Olufsen, chief policy officer of the Danish Maritime Authority, said the first green corridors will “play an important role in their capacity to show how the green transition can work in practice.”

Bo Cerup-Simonsen, CEO of the Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller Center for Zero Carbon Shipping, said the green corridor concept serves at least two purposes: “Getting the green value systems going to attract the initial customers and investors, and then aggregating demand to create a sustainable longer-term business model with greater demand.”

“I think that’s a working hypothesis of the green corridor which seems to hold,” Cerup-Simonsen said. “That’s a very strong proposition … that will [create] initial scale, and that should inform the global policy system.”

Eamonn Beirne, a deputy director in the United Kingdom’s Department for Transport, said he is encouraged. “In a sector with a reputation for rigidity or moving too slowly, we’ve been really thrilled with the momentum worldwide as the signatories and industry players alike have made green corridors a cornerstone of their respective journeys to zero-emission shipping.

“I think it’s crucial that the commitments at events like COP26 or this one today translate into action, and it’s been really great to see some of that happening.”

Because there are so many moving parts to the industry across the globe, there needs to be a playbook with common language and identified critical success factors, American Bureau of Shipping CEO Christopher Wiernicki said.

“One of the biggest things with green shipping corridors is you need data. Data is going to be so important in this process because without data you cannot make the right decisions,” he said.

Sandra Kilroy, senior director of engineering, environment and sustainability at the Port of Seattle, continued that theme, saying standardization is critical. She said the ports of Seattle and Los Angeles have begun collaborating for this reason.

“There’s a lot of differences, obviously, between what we’re doing,” she said. “But [the more] that we can be consistent in how we’re approaching the policy is going to be really helpful because we’re both picking up the phone and having meetings in D.C. trying to help institute the policies we need in place to move this forward.”