NERC has posted in draft form the first results from the Interregional Transfer Capability Study ordered by Congress in 2023, summing up the transfer capabilities between transmission planning regions in North America.

The ERO Enterprise — including NERC, the regional entities and all North American transmitting utilities — has been working on the ITCS since Congress mandated the study in the Fiscal Responsibility Act. Under the FRA, NERC must file the finished report with FERC by December. The study includes “significant collaboration” with a host of additional stakeholders, including transmission planners, owners and operators; planning coordinators; state, provincial and federal partners; utilities; and trade groups.

The Transfer Capability Analysis released Aug. 28 represents Part 1 of the ITCS, following the publication of NERC’s Overview of Study Need and Approach in July. (See NERC Promises 1st ITCS Results by August.) Results from this installment will be used for Part 2, a draft of which is scheduled to be released in November and will recommend prudent additions to transfer capability that could strengthen grid reliability.

Part 3, laying out recommendations to meet and maintain total transfer capability, is expected to be released in draft form in November as well. A final installment focusing on Canada is to be published in the first quarter of 2025.

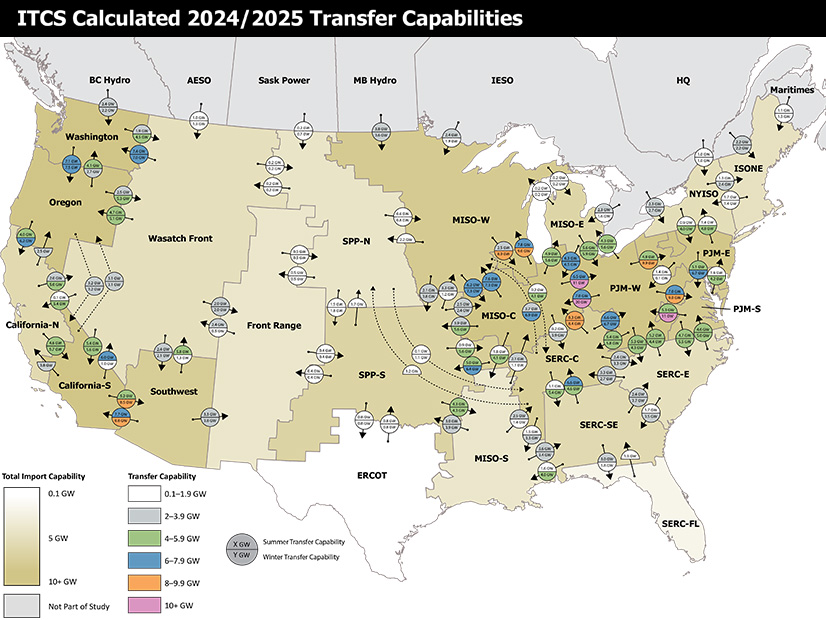

The transfer capability analysis covered two different base cases: one based on summer 2024, the other on winter 2024/25. NERC used the transmission planning regions identified in FERC Order 1000 as a starting point for studying transfer capacity, as required in the FRA. The project team further subdivided these regions in some cases to account for the geographic variations and resulting internal transfer constraints in some areas.

Performing the transfer analysis involved simulating unplanned outages of various system elements during transfer analysis to discover the point at which the grid could not maintain reliability. The last step prior to a reliability issue was labeled the first contingency incremental transfer capability. This was added to the base transfer level, derived from scheduled interchange tables for each study case, to arrive at the total transfer capability of each.

The study found that transfer capability “varies seasonally and under different system conditions [and] cannot be represented by a single number.” A map shared by the team showed that winter and summer transfer capabilities are closely matched in some cases — such as Washington to Oregon, which shows just a 200-MW difference between seasons — while other cases exhibit a wide disparity.

For the link between California South and the Wasatch Front, for example, the transfer capacity in summer was reported as 6 GW, as opposed to just 1 GW in winter. MISO West reportedly could transfer 8 GW to PJM West in winter, but just 2.5 GW in summer.

Other areas indicated no transfer capabilities in one season at all. SERC Florida was recorded as having a capacity of 1.3 GW into SERC Southeast in summer and none in winter, while California North reported a transfer capability to Oregon of 2.5 GW in winter and nothing in summer.

NERC said transfer capabilities tended to be higher in the West Coast, Great Lakes and Mid-Atlantic areas, and lower in the Rocky Mountain states, Great Plains, Southeast and Northeast. Limited transfer capability exists between interconnections. This installment includes transfer capabilities from Canada into the U.S., but not the other way around; Part 4 will cover transfer capabilities from the U.S. to Canada and between Canadian provinces.

In a media release, NERC warned that Part 1 should not be taken as a measure of energy adequacy in itself, but rather as simply a statement of the “magnitude of transfer capability.” That will be examined when NERC explores prudent additions “based on a holistic view of transmission and resource availability” in Part 2.