Despite recent transparency improvements, broader efforts are needed to address underlying concerns about a lack of regulatory oversight of local transmission costs in New England, according to panelists on a recent webinar held by Advanced Energy United.

Speakers at the Nov. 4 webinar emphasized the need to address the “regulatory gap” that allows most transmission spending in the region to avoid scrutiny.

The regulatory gap is a “consumer confidence issue,” said Jackie Bihrle, managing attorney at the Massachusetts Attorney General’s Office. “Consumers should be able to have confidence that utility spending is the least-cost, most effective solution, and that has dwindled with this gap.”

Local transmission projects, known as asset-condition projects (ACPs) in New England, are typically upgrades of existing assets deemed to be aging or deteriorating. The projects are not subject to competitive bidding processes or regional planning processes, and the transmission owners recover costs through FERC formula rates.

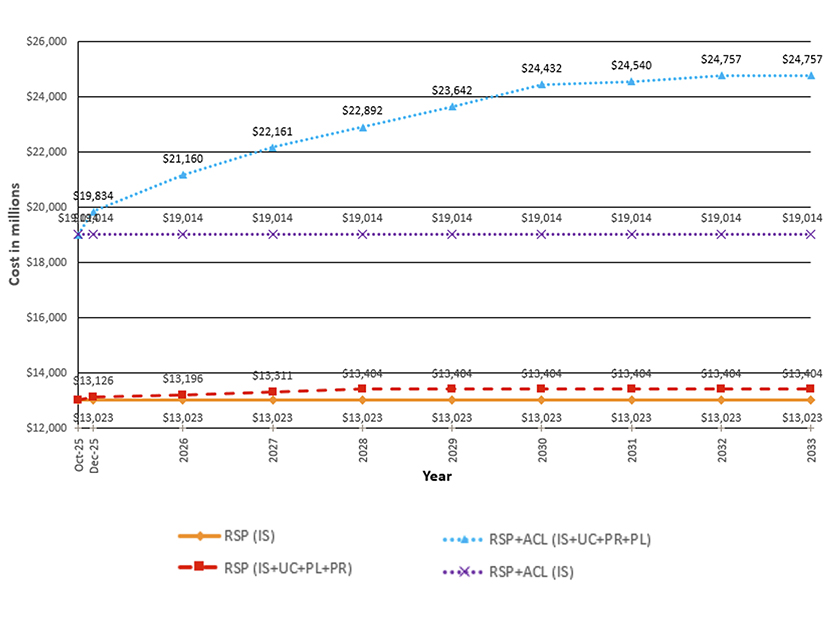

Asset-condition costs have risen significantly in New England in recent years. The region’s transmission owners reported nearly $4 billion in ACPs placed in service between 2020 and 2024, and the companies forecast spending in 2025 to total nearly $1.5 billion.

While substantial spending is necessary to maintain the region’s grid, more safeguards are needed to ensure this spending is as cost effective as possible, the panelists agreed.

Local transmission spending is subject to “the lightest touch review possible” at the federal level, and projects generally face minimal scrutiny from state-level permitting processes, said Matthew Christiansen, partner at Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati and former FERC general counsel.

He said there is clear evidence that transmission spending has been concentrated in recent years on projects that are not subject to regional planning or competitive solicitation processes. Along with increased spending on local projects, “you actually see the same thing with regional projects that are exempted from competition,” he said.

Christiansen added that formula rate procedures at FERC have created structural difficulties for stakeholders seeking to challenge the prudency of costs. Instead of requiring TOs to prove the prudency of investments, formula rates shift the burden of proof to third parties contesting the prudency of the spending.

“It really does change the playing field in terms of what has to be proven, in a way that makes it much more likely that costs will ultimately be passed through to ratepayers,” Christiansen said, adding that consumer advocates’ ability to challenge costs is typically minimized by limited resources and “informational asymmetries” between them and TOs.

In June, ISO-NE agreed to take on a non-regulatory “asset condition reviewer” role to provide increased transparency into project spending. In a recent update, the RTO said the role is “envisioned to provide an independent review and opinion of asset-condition projects submitted for review by the TOs,” which could help inform formula rate challenges with FERC. (See ISO-NE Gives Update on Asset Condition Reviewer Role.)

“It will help, I think, on the transparency issue,” Bihrle said. “This isn’t going to completely solve the underlying problem, but we think it’s a really important step in the right direction.”

The insight and “objective opinions” provided by ISO-NE could “provide some information upon which interested stakeholders could challenge asset-condition spending at FERC,” Bihrle added.

Discussing potential solutions to the broader issue, Christiansen said it is easier to diagnose the problems than it is to provide answers that would not have unintended consequences.

He said FERC could establish a dedicated “technical office” to perform targeted audits of local projects; this could provide a good starting point for identifying issues or trends.

Claire Wayner, senior associate at RMI, emphasized the importance of coordinating local and regional transmission projects and looking for opportunities to right-size projects to maximize potential benefits.

She said coordination and right-sizing discussions need to occur early in the planning process, as it can be hard to address these questions by the time projects reach state permitting proceedings.

“This cannot be solved alone by increased state-level oversight,” Wayner said. “We need to see regions do more regional-first planning.”