When surging seawater inundated Con Edison’s 13th Street substation during Superstorm Sandy in 2012, explosions lit up the New York City sky. As control room staff were being rescued by boat, a million people in its service area were left in the dark, five times as many as the previous high from Hurricane Irene just a year earlier. If water and electricity are a bad combination, salt water and electricity are worse.

As part of a billion-dollar resilience program, it took nearly a decade and $180 million for Con Ed to harden that substation to withstand future storms, elevating the control room two stories, installing corrosion-resistant fiberglass components, and adding retaining walls and floodgates.

Storm surge events like Sandy offer insights into what the worst of sea level rise may do to an area’s infrastructure and how the power industry needs to think about this slow-moving but inevitable threat.

This is the next in a series on how climate extremes are impacting the grid; earlier articles explored heat waves, wildfires and extreme precipitation.

Subtle, Until It’s Not

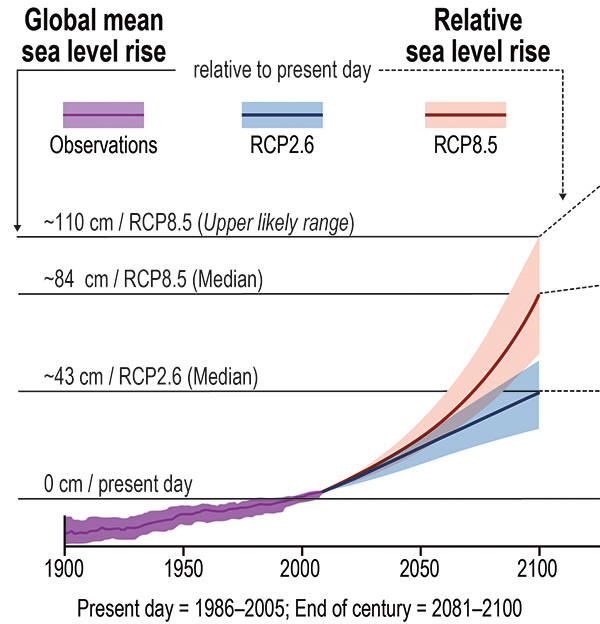

It’s easy to think of sea level rise as a subtle and future challenge: After all, sea level rose by only 0.14 inches per year from 2006–2015. However, that was 2.5 times the average annual 0.06-inch rise throughout most of the 20th century. In total, the seas have risen 8 to 9 inches since the late 1800s, when Edison was building his first power plants.

Even looking at a 30-year time frame, the threat sounds concerning, not catastrophic. If you play around with NOAA’s sea level rise map and look at what the estimated rise by 2050 will do, it’s hardly “Waterworld.” The scariest numbers — if all of Antarctica’s up-to-three-mile-thick ice were to melt, global sea levels would rise by around 200 feet, and Greenland’s ice sheet would add an additional 23 feet of sea level rise — aren’t forecast this millennium.

But 2050? The next 30 years see an additional 8- to 10-inch rise if the midpoint of climate scenarios plays out. There’s little evidence, however, that policy changes and demand spikes won’t send us stumbling into poorer climate scenarios. Worse: The high-emissions scenario adds a couple of inches to that estimate. Worst: The Antarctic ice sheets join the party.

The real concern is when we look out to the end of the century, and in an industry that builds infrastructure that’s expected to last into the 2100s. That’s where we should be focused. While most scenarios range from 16 inches to three feet in rise over today’s sea levels, some threats could add significantly to that. Most concerning is the potential collapse of Antarctica’s Thwaites Glacier (or, as his friends call him, “Doomsday”), which not only holds enough ice to raise sea levels a couple of feet, but also is the stopper holding back much of the massive West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

Sea levels rise not only because ice caps and glaciers are melting, but also because the oceans expand as they warm. There’s also displacement as land held down by the weight of ice rises as that ice thins.

All Coasts are not Equal

It’s easy to assume sea level is, well, level in the same way a water level finds equilibrium. But the global mean sea level is just an average. The coastal impact will vary significantly, based on how the earth rotates, how the oceans flow and how tectonic plates are moving; it’s why the Pacific Ocean side of the Panama Canal is eight inches higher than the Atlantic side.

For the U.S., NOAA’s model predicts the Gulf Coast will rise 14 to 18 inches by 2050 and the East Coast from Virginia to Maine will rise 10 to 14 inches but the Pacific Coast will rise only 4 to 8 inches. This means infrastructure owners have to plan and prioritize their upgrades using detailed local projections.

The NOAA mapping tool uses mean higher high water (MHHW), not mean sea level, as the starting point, as it represents the elevation of the normal daily tide movements where the shoreline normally is inundated. The MHHW is the high point of “normal.” If the MHHW rises, not only is the daily sea level higher, but also king tides and storm surges start from a higher baseline.

Oh, We Do Like to be Beside the Seaside

Face it: We love the ocean. More than swimming in it or gazing at it, we love shipping goods across it, cooling power plants with it, sucking oil out from under it and reclaiming it to expand cities.

All of this commerce means coastal cities and counties are home to more than a third of Americans. The result: While around 13 million homes are at risk of flooding in the upper end of NOAA’s regional scenarios, the infrastructure many millions more depend on is at risk. That infrastructure ranges from airports (12 of the nation’s busiest airports have runways at risk of storm surge) to hospitals to water treatment plants.

The energy sector is no exception: Many power plants, substations and transmission corridors were historically sited near water for cooling and logistics. These assets may be damaged by storm surge, tidal flooding and erosion. Additionally, buried cables, conduits, control systems and transformers near the coast are at risk of saltwater intrusion as groundwater rises.

Asset owners will need to invest in moving, raising or otherwise hardening those coastal assets if they are to maintain service reliability and manage the cost of insuring those assets.

Substation by the Sea

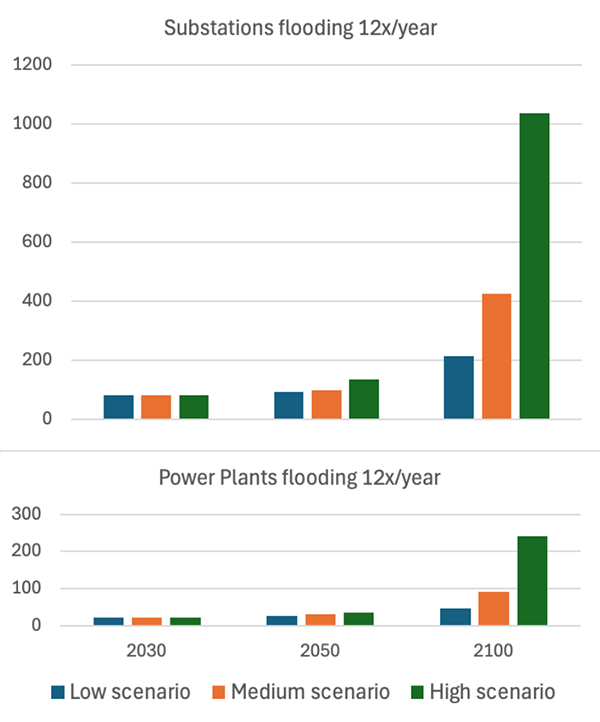

A significant number of energy assets are built by the shore: 2,681 power stations and 8,750 substations, according to the Union of Concerned Scientists. The UCS study looked at all critical infrastructure: power and substations, public safety and health facilities such as hospitals and fire stations, educational institutions, public and affordable housing, industrial contamination sites, and government facilities.

Some states have significantly more critical infrastructure at risk than others, with Louisiana (334) and New Jersey (304) most at risk by 2050 under a medium sea level rise scenario. As time goes on, Florida leaves all other states behind, and by 2100, it has more than three times the number of critical infrastructure assets (4,599) at risk than any other state under the high sea level rise scenario.

In terms of the energy sector, by 2050, 151 electrical substations are likely to be heavily affected by flooding at least twice annually under a medium sea level rise scenario. By 2100, more than 1,000 substations and 240 power plants are at risk of monthly flooding under a high sea level rise scenario.

Companies with assets near the coast can explore the interactive map to discover which critical infrastructure assets in are at risk.

Preparing to be High and Dry

The IEEE model for wildfire preparedness discussed earlier in this series includes three lines of defense: prevention, mitigation and proactive response, and recovery preparedness. Sea level rise needs a similar approach, though in its case, utilities can’t prevent it.

Most actions fall into the second line of defense: mitigating damage by hardening, raising or moving infrastructure inland. Con Ed’s post-Sandy upgrades, for example, included “walls to keep water out of substations, submersible equipment that keeps operating even when submerged in salty water, stronger poles and wiring for the overhead system, transformers that can be installed quickly and other measures,” a spokesperson told RTO Insider.

“It also included the reconfiguring of two electric networks in Lower Manhattan, allowing us to shut off service (due to flooding) to customers near the coast while leaving the customers located more inland to stay in service.

“We estimate that the upgrades made since Sandy have prevented more than 1.2 million outages.”

In some areas, there’s a tradeoff to consider: Do you lessen the chance of wind damage by undergrounding assets, or does that increase their chance of being damaged by sea level rise? And, as with any emergency, having islandable backup power for hospitals and other critical infrastructure will improve safety and resilience.

For grid and power plant owners and operators with assets in coastal areas, the only good news about sea level rise is that it’s relatively predictable and there’s time to act. While it may not save assets from storm surge as named storms become more frequent, there is time to prepare for 2050- and 2100-level sea levels.

Preparation Starts with Data

Infrastructure upgrades start with good modeling to understand what’s at risk. Just like with other climate-exacerbated disasters, asset owners shouldn’t base plans on outdated FEMA maps; utilities need forward-looking, climate-adjusted models that include groundwater rise and compound flooding. And given the expected variation in sea level rise along coasts, local studies are critical, particularly for major cities.

While watching Ken Burns’ “American Revolution” recently, I was surprised to see a map of Boston that looked nothing like the Boston I know. Today, it has a significant amount of reclaimed land; half the city is built on landfill and earth moved from hills flattened after the tea went into the harbor. As a result, a lot of its important infrastructure is at sea level. As RTO Insider’s Jon Lamson reported last year, a report delves into the local impacts that could be felt, and it’s a solid starting point for prioritizing upgrades.

Similarly, following the big freeze in Texas, the state’s regulators, ERCOT and state emergency management officials mapped its critical infrastructure to ensure better coordination in future emergencies.

For areas that have no granular studies, the NOAA tool offers a range of local scenarios that map low, intermediate and high projections up to 2100 and that can be overlaid onto existing infrastructure maps.

Along with physical preparation, utilities need to incorporate climate projections into integrated resource planning and state PUCs need to align requirements with future climate risks, not historical conditions.

“We went to our regulator and got approval to invest $1 billion to fortify our energy systems against extreme weather,” the Con Ed spokesperson said. “Fortifying the energy systems against extreme weather is now part of our ongoing planning and investing.”

Regulators in areas that haven’t had a Superstorm Sandy-style wakeup call would be well-served by helping utilities invest in fortification before a similar crisis strikes.

The Calm Before the Storm

Proactive response is critical, especially for storm surge, which is sea level rise on steroids. With larger storms and the surge starting from a higher baseline, the threat is amplified compared to past storms.

It’s not feasible to move or harden all infrastructure that could be affected by storm surge, but acting ahead of a storm can minimize damage. When storm surge is expected, powering down at-risk infrastructure may inconvenience customers, but ultimately leads to shorter blackouts and less equipment damage, as shown in Superstorm Sandy when Brooklyn’s Farragut substation was proactively powered down hours before the 13th Street substation was involuntarily powered down by sea water. Farragut was de-energized when it was inundated, and equipment was quickly dried and power restored by noon the day after the storm.

The third line of defense, recovery preparedness, is essential as well. It’s an investment that will pay off across all types of crises. For example, Con Ed’s hardening program included buying 110 bucket trucks and staging them an hour outside of Manhattan, so crews flown in from other states can be deployed rapidly for future recovery efforts.

No Utility is an Island

Sea level rise will affect many types of coastal infrastructure, so coordinated plans should be developed to use construction projects. It is planning that should be done at the state or national level, though many states still are using 20th-century assumptions for 21st-century risks.

Some measures, such as building sea walls, may help entire cities and their infrastructure. But seawalls are expensive and not an option in many areas due to geography or geology. Miami, for example, is built on porous limestone, so a barrier around the edge would do nothing to stop the water from seeping up through the ground in low-lying areas. Parts of Miami already experience sunny-day flooding during high tides, and some are suggesting it’s time to talk about managed retreat. But as one of the most vulnerable cities in the country, Miami’s been proactive in assessing its risk and planning a coordinated response. Its Sea Level Rise Adaptation Plan provides a complete, though sobering, look at everything needed to keep Miami inhabitable as the seas rise.

For many utility upgrades, it will be more cost-effective to coordinate with other services that need to be hardened than to have all affected infrastructure owners prepare piecemeal for the coming sea level rise.

Physics, not Politics, Must Guide Us

The grid and power system must be redesigned for the coastline we will have, not the one we remember. The physics of rising seas is not negotiable. While storms will give us a taste of how damaging rising sea levels can be, there is time to prepare for the everyday sea level rise that utilities and grid operators in coastal communities will face.

Utilities, regulators and policymakers must treat this as an engineering and planning challenge, not a political one. While climate reports are being removed from federal agency websites, leaders in affected communities know they can’t afford to waste time debating whether it’s happening and why.

For power plant and grid owners and operators, there’s no simple choice between investing now to avoid catastrophic outages or paying later in dollars and lives. The cost of proactive resilience is massive for a problem of this scale. What is clear is that we must understand where the risks are before we can prioritize where to invest.

The seas are rising whether we prepare or not. The grid needs to rise to the challenge.