For most of the electrical industry’s history, weather was a constraint we designed around. Climate, by contrast, now is a system we operate inside of: a wild, unstable system.

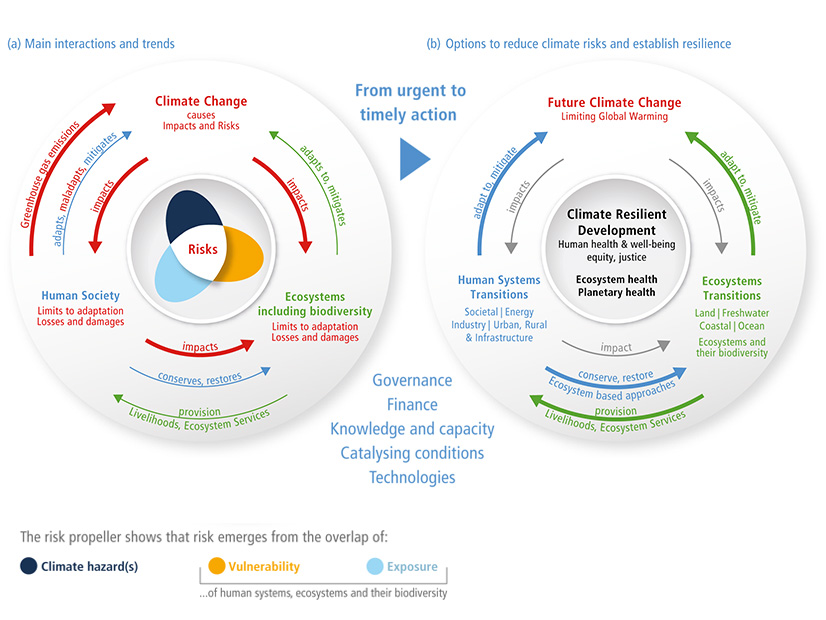

That distinction matters more than many grid leaders, regulators and policymakers have absorbed. Extreme heat, wildfires, intense rain, drought and sea level rise often are approached as separate hazards — each deserving its own planning docket, modeling exercise or capital program. And while this column just completed a series on the impact of each hazard on the grid, they are not a collection of independent risks; they are a tightly coupled system of climate-driven stresses that interact, compound and persist in ways the grid never was built to handle.

Climate risk no longer is an environmental problem. It’s a governance, planning and management problem. And it sits squarely on the desks of utility executives, system operators and policymakers.

From Discrete Events to Systemic Risk

The industry knows how to deal with events. We respond to heat waves, storms, fires and floods when they occur individually. Mutual assistance is activated, crews are staged, emergency declarations are issued and restoration begins.

To submit a commentary on this topic, email forum@rtoinsider.com.

Climate change has turned those events into conditions.

Heat no longer is a single-day peak but a multiday, multinight stress that simultaneously drives record demand, reduces generation efficiency and lowers transmission capacity. Drought is not just a hydroelectric issue; it constrains thermal cooling, increases wildfire risk and exposes weaknesses in the water-energy nexus. Wildfires are not seasonal hazards but year-round threats with cascading impacts on air quality, solar output, worker safety and liability exposure. Extreme rainfall doesn’t merely knock down lines; it floods substations, undermines foundations and complicates recovery logistics. Sea level rise isn’t a future storm-surge problem; it’s a slow, permanent redrawing of where infrastructure can safely exist.

Taken together, these risks do not stack neatly. They collide.

A heat dome can arrive during a drought, elevating fire risk. Fires strip vegetation, increasing the likelihood of debris flows and flash flooding when rain eventually comes. Flooded substations disrupt power to water systems just when pumping capacity is needed most. Smoke degrades solar output and limits air operations for line inspections. Each stress amplifies the next.

We can’t plan for each hazard in isolation.

Polycrisis, Meet Multisolving

Two terms I keep coming back to as I consider how the industry will manage in a future in which uncertainty is the norm are polycrisis and multisolving.

The term “polycrisis” was coined by French complexity theorists in the early 1990s and popularized in the early 2020s as the planet struggled with a pandemic, climate change, wars and economic instability. Climate change interacts with energy sources, generation, transmission and distribution infrastructure and the safety, well-being and economic stability of residential and commercial customers. It interacts with other critical infrastructure systems that both depend on and support the grid. And this is happening against a backdrop of income inequality, declining health outcomes, population migration and unstable federal emergency management support. Climate is not a single crisis for the grid.

“Multisolving” was coined by Dr. Elizabeth Sawin and focuses on the positive flipside of the coin: solving for one problem can solve for others. Think of it as the BOGO of the solutions crowd. For the grid, building resilience against one extreme challenge comes with the bonus of creating resilience against others, with a further ripple effect of improving reliability and lowering corporate exposure. Similarly, decarbonizing the grid with renewables and energy storage comes with the bonus of lowering exposure to fuel prices, increasing grid stability and improving the health of communities near power generation.

They are both linked to unintended consequences: polycrisis in a negative sense where one challenge results in multiple, compounding challenges; multisolving in a positive sense where one solution solves more than one challenge.

Grid Resilience in the Time of Climate Change

Most grid planning frameworks still assume three things that no longer hold: historical climate baselines, independent hazards and short disruption durations.

Reserve margins, resource adequacy models and integrated resource plans often are still calibrated to yesterday’s weather. Reliability metrics reward fast restoration after discrete outages, not the ability to avoid catastrophic system failure during prolonged, overlapping stresses. Yesterday’s n-1 contingency planning won’t work when climate delivers n-many failures simultaneously.

The problem isn’t a lack of data. Climate science has advanced rapidly, and hazard modeling is more sophisticated than ever, assuming inputs and assumptions are adjusted for today’s reality. The problem is institutional inertia: Planning processes and regulatory structures have not evolved at the same pace as the risk landscape.

The industry needs to focus on correlation risk. Heat waves reduce solar efficiency at the same time demand peaks. Wildfire smoke causes “wiggling” in photovoltaic output while also limiting crew deployment. Flooding disrupts electricity, communications and transportation at once. These interactions are predictable and need to be built into planning assumptions.

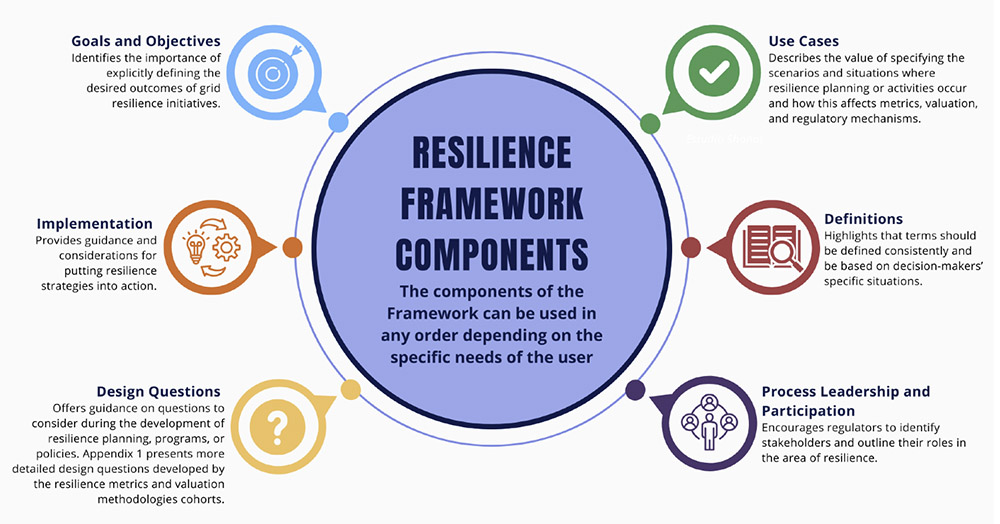

There are resources to help with this planning challenge, such as the National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners’ tools for public utility commissions.

This planning needs to be done against a backdrop of rapidly accelerating risk. The creators of the First Street Correlated Risk Model found, “the frequency of losses resulting from major climate disasters in the U.S. has increased over fivefold in the past four decades, with climate change and increased development in vulnerable areas being the primary drivers.”

And there’s no one-solution-fits-all. Existing adaptation approaches typically assume rather simplified models, an IEEE study found. “The reality, however, is that climate change patterns and the uncertainties they introduce can differ regionally, complicating the formulation of effective countermeasures.”

As climate hazards become more frequent, more extreme and more varied, the industry can’t afford to rely on plans that appear robust on paper but are brittle in practice. The industry must invest in comprehensive planning and prioritize infrastructure upgrades that address multiple risks.

Climate Risk Has Become a Balance-Sheet Issue

The most underappreciated shift may be financial rather than technical.

Climate exposure is reshaping utility balance sheets. Wildfire liability has driven bankruptcies and forced restructuring, insurance providers are retreating from high-risk regions or sharply raising premiums, and credit rating agencies are flagging climate exposure as a material risk. Capital costs are rising fastest for utilities with the greatest climate vulnerability, often the same utilities facing the largest infrastructure reinvestment needs.

In effect, climate risk is becoming a de facto regulator, often acting faster and more bluntly than public utility commissions.

This matters because resilience investments too often are framed as discretionary or extraordinary: nice to have if regulators approve, deferrable if rates are politically sensitive. But in reality, failing to invest in resilience now simply shifts costs forward, where they reappear as higher borrowing costs, insurance gaps, emergency repairs and, ultimately, customer harm.

Swiss-Re Institute, which studies the risk landscape closely — because reinsurance companies are the ones pricing the growing risk — said, “Ongoing risk assessment is necessary to ascertain how resilient infrastructure is. Assets that are poorly maintained are more vulnerable.”

Conversely, today’s resilience investments can pay dividends beyond repairing and preparing for the same risk. Think about the $1 billion, four-year Con Edison storm fortification initiative following Superstorm Sandy: It was triggered by outages following a storm surge, but is paying dividends as the utility faces ice storms, heat waves and more.

Executives who treat climate adaptation as an environmental compliance issue are misreading how quickly financial markets are moving.

No Utility is an Island

Another lesson emerging across climate hazards is that grid resilience cannot be built in isolation. Power outages cascade. They shut down water pumping and wastewater treatment. They cripple communications networks. They undermine emergency response and health care delivery. During fires and floods alike, loss of electricity turns manageable crises into life-threatening ones.

Yet in many states, energy planning remains siloed from water utilities, emergency management agencies, transportation departments and telecom providers.

Cross-infrastructure coordination can’t be ad hoc or occur only after a disaster. Integrated planning and response reduce both risk and cost. If infrastructure needs to be protected from rising sea levels, for example, it’ll be more cost effective if all affected agencies coordinate resilience investments, hardening power, water, wastewater treatment and roads simultaneously.

At the same time, a region may be more of an island than ever before: If multiple states face an event at the same time, like the winter storm that recently shut down a solid slice of the lower 48, mutual aid agreements break down as crews are needed locally and flying in distant crews becomes impossible. Mutual aid is ideal, but some disasters will be more Lord of the Flies than Swiss Family Robinson.

Resilience is not something the power sector can buy on its own. It is an interdependent system, and governance structures have to reflect that reality.

What a Climate-adjusted Grid Strategy Actually Looks Like

If climate risk is now a core management challenge, what follows is not a checklist of projects but a shift in mindset.

First, resilience must move beyond asset hardening toward system flexibility. Hardening substations and elevating or undergrounding equipment remain necessary, but they are insufficient on their own. Islandable microgrids, distributed energy storage and modular recovery strategies allow systems to absorb shocks rather than simply resist them. Flexibility — not brute strength — is what enables systems to function under compound stress.

Second, planning must explicitly account for duration. Multiday heat waves, weeks of wildfire smoke, yearslong droughts and permanent sea-level rise pose fundamentally different challenges than short, sharp events. Planning processes that focus on peak hours or single-day extremes underestimate both operational strain and human fatigue.

Third, we must align incentives with future conditions. Regulators play a critical role here: Cost-recovery frameworks still favor post-event rebuilding over preemptive adaptation, even though avoided outages and avoided disasters deliver far greater public value. Utilities, for their part, need to treat resilience as a core dimension of service quality — not a regulatory add-on.

Fourth, reliability metrics need updating. Measures that prioritize restoration speed after outages do little to encourage investments that prevent catastrophic failure in the first place. In a climate-altered grid, success increasingly looks like outages that never happen, liabilities that never materialize and emergencies that never escalate.

Leadership in a Non-Stationary World

The grid already is operating inside a climate-stressed environment. The question facing leaders and policymakers is not whether the lights can be kept on during the next storm, it is whether governance structures, planning tools and investment frameworks can evolve fast enough to manage permanent instability.

That evolution will be uneven. Some utilities and system operators are already internalizing climate risk as a core design constraint. Others remain trapped in a compliance mindset, waiting for clearer regulatory signals or the next disaster, legal action or insolvency to force action.

The future of our industry will not be defined by how cheaply it delivers electrons, but by how well it absorbs shock, and that can happen only if leaders treat climate risk as the multidimensional management challenge it has become.