In Massachusetts, a state with some of the most ambitious decarbonization policies in the country, fundamental disagreements between utilities and consumer advocates threaten to derail the transition from natural gas before it even gets off the ground.

While technical in nature, these disagreements ultimately boil down to different visions of the role of the gas system — and the role of its utilities — in a decarbonized Massachusetts. With affordability already dominating energy politics throughout New England, the direction and effectiveness of the state’s transition could have major implications on consumer costs for years to come.

The arguments over the future of the state’s gas system are not new; many of the underlying disagreements date back to the Department of Public Utilities’ multiyear and at-times-controversial investigation into whether to maintain the system while decarbonizing the fuel, or transition completely away from it altogether.

Initiated in 2020 under Gov. Charlie Baker (R) at the request of then-Attorney General Maura Healey (D), the investigation highlighted the major differences in the strategies proposed by the investor-owned gas utilities and climate and consumer advocates.

Throughout the proceeding, the utilities promoted a strategy reliant on alternative fuels and hybrid electrification. This proposed approach would keep much of the state’s gas network in place to back up electrified heating while blending hydrogen and “renewable” natural gas (RNG) into the system to lower the carbon intensity of the fuel.

To submit a commentary on this topic, email forum@rtoinsider.com.

By contrast, climate advocates pushed for a full-electrification strategy. They argued that alternative fuels like RNG and hydrogen are expensive, scarce and ultimately non-viable for residential heating at a large scale, and that a hybrid electrification strategy would lead to excessive costs associated with building out the electric system while continuing to invest in the existing gas network.

The DPU concluded the investigation in late 2023 under new leadership appointed by Gov. Healey, who took office at the start of that year. While climate advocates had criticized the DPU under Baker for relying on utility-hired consultants to conduct the technical analysis for the investigation, the department ultimately agreed with the advocates on the core issues.

With the order, the department established a regulatory framework “to move the commonwealth beyond gas and toward its climate objectives.” It expressed skepticism about the cost effectiveness of a “broad hybrid heating strategy” that maintained the bulk of the state’s gas distribution system. The DPU also declined to allow utilities to recover costs associated with procuring alternative fuels, citing concerns about “costs, availability and the treatment of renewable fuels as carbon neutral.”

The order required the utilities to file “climate compliance plans” plans every five years, evaluate non-pipeline alternatives when making gas system investments, cease promoting gas expansion with ratepayer funds and pursue targeted electrification pilot projects (D.P.U. 20-80-B). (See Massachusetts Moves to Limit New Gas Infrastructure.)

But in the two years following the landmark order, the conflicts that defined the DPU’s investigation have continued in the regulatory proceedings that have branched out from the ruling.

Across proceedings related to gas demand forecasting, pipe leaks, the climate compliance plans and the future of the region’s only LNG import terminal, the utilities have butted heads with proponents of the transition.

The utilities have been slow to embrace gas alternatives and pipe decommissioning at scale, which their critics attribute to the companies’ profit motive and reluctance to give up their traditional business model.

In contrast, the utilities have dug in on the language of customer choice, and they argue they lack the legal authority to decommission pipes without obtaining the consent of all affected customers. They argue that if a single customer on a pipeline segment is not willing to give up gas service, they cannot decommission the pipeline, even if electrified alternatives are available.

While advocates dispute this reading of state law, the question about the utilities’ authority to retire parts of the gas system remains unsettled, as does the underlying question of whether the state will ever be able to get its investor-owned utilities to embrace a transition away from gas.

The Obligation to Serve

According to the state’s gas distribution companies, their obligation to provide gas to existing customers stems from their franchise rights as regulated utilities.

“In exchange for a monopoly franchise, LDCs [local distribution companies] must actually provide natural gas service to customers absent the legislature rescinding their franchise charter or other clear legislative action alleviating the obligation to serve customers residing in a franchise territory,” the companies wrote in a joint filing in October in response to an inquiry by the department (D.P.U. 25-40, et al.).

In contrast, climate and consumer advocates argue the utilities’ obligation to serve does not prohibit the companies from substituting gas service for alternatives — such as networked geothermal or other electrified heating technologies — when viable alternatives are available. They point to a 2024 change in state law, which, according to its the lead senator in the negotiations, amended the obligation to serve to prevent issues related to holdout customers. (See Mass. Clean Energy Permitting, Gas Reform Bill Back on Track.)

The 2024 law directed the DPU to consider the public interest and the availability of non-gas alternatives for heating and cooking when ruling on petitions for gas service. It also explicitly authorized the department to “order actions that may vary the uniformity of the availability of natural gas service.”

The utilities argue that this change in law changed neither the “the legal foundation for the obligation to serve existing customers” nor the “obligations of the LDCs to existing customers.”

The Massachusetts Attorney General’s Office, the official ratepayer advocate in the state, disagrees. It argued in response that the DPU is well within its authority to authorize the disconnection of gas customers to advance the public interest.

With the 2024 changes to state law, “the legislature aligned the obligation to serve with the commonwealth’s climate goals by expanding the power of the department and articulating a balancing test to weigh the interests of the commonwealth with the interests of the individual customer,” the AGO wrote.

“It is illogical to suggest that the LDCs and department lack the authority to deny or discontinue gas service to promote the public interest in cost-effective decarbonization,” it added.

The DPU has yet to rule on the question of the utilities’ obligation to serve, and its interpretation of state law could face legal challenges from the utilities if the department ultimately sides with the consumer advocates. The potential impacts are substantial.

“It’s a very important issue,” said Jamie Van Nostrand, who led the DPU from 2023 through fall 2025 and oversaw the department’s order on the gas decarbonization investigation. He is now policy director for the Future of Heat Initiative. (See Outgoing Mass. DPU Chair Van Nostrand Discusses Gas Transition.)

Under the utility interpretation of the statute, “it’s all about customer choice, and if the customer wants to keep their gas, end of discussion — no decommissioning,” he said. “That is a bad outcome, because we need to have a managed transition.”

Stranded Assets

A managed transition, Van Nostrand said, is essential for long-term energy affordability in the state. Since leaving the DPU in the fall, he has been vocal in the ongoing affordability debates in the state, raising the alarm about the trend of increased spending on gas infrastructure.

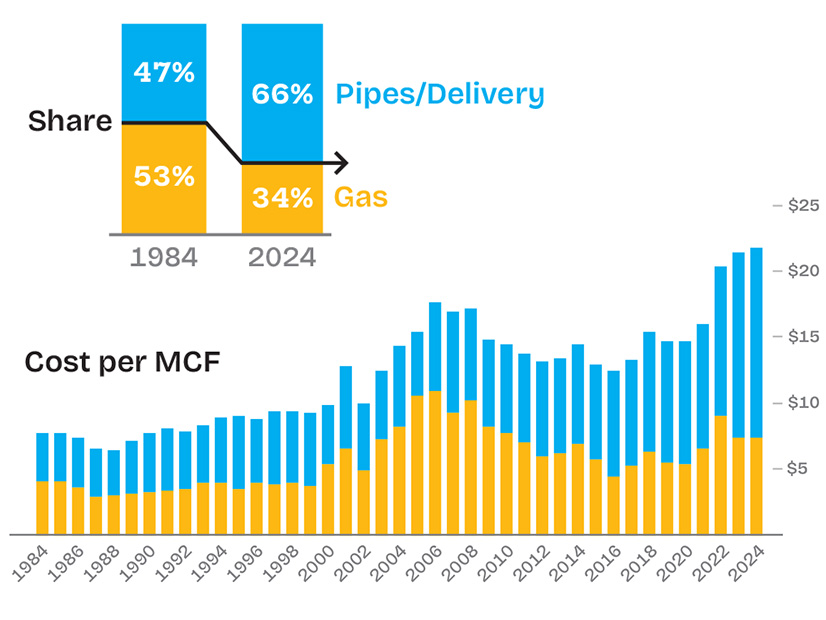

According to an analysis by the Future of Heat Initiative, gas utilities in the state more than doubled their assets between 2014 and 2024, significantly increasing customer costs despite a 22% decline in per-customer gas demand.

“If you can’t shrink the system as the throughput goes down, delivery charges go through the roof; it’s simple math,” Van Nostrand said.

A large portion of this spending has occurred under a state program that gives the gas companies expedited cost recovery for replacements of leak-prone pipes. The costs of the Gas System Enhancement Plan (GSEP) program have risen rapidly in recent years, totaling $814.4 million in 2024. In total, the utilities spent more than $4.7 billion through the program between 2015 and 2024.

In an attempt to rein in the spending, the state has made several amendments to the GSEP statute in recent years to increase emphasis on pipe relining and repair, along with non-pipe alternatives, including networked geothermal.

But despite the efforts to curb spending and prevent stranded assets, costs have continued to rise, and traditional pipe replacements continue to constitute essentially all GSEP projects.

According to the utilities, the rise in GSEP costs is the result of the effects of inflation and supply chain constraints on the prices of materials and labor. In a written response to questions, Eversource Energy, one of the two major gas utility companies in the state, wrote that it already has replaced the bulk of the most accessible pipes and that its remaining portions of leak-prone pipes tend to require more complicated and expensive construction.

The company said an increased focus on pipeline repair would not help limit costs, writing that “there is no viable method for ‘repairing’ leak-prone infrastructure in a manner that obviates the need for replacement or that achieves the level of public safety that is achieved through replacement.”

“Prioritizing repairs over replacement can lead to higher longer-term costs, as sections of leak-prone pipes will likely require multiple future repairs and ultimately be replaced anyway, at which point the cost of replacement will have likely increased,” it added.

Van Nostrand did not dispute the underlying economic conditions, but he did highlight the attractive financial proposition to the utilities of expedited cost recovery, as well as the regulatory incentive structure that enables the utilities to earn more money from capital investments than from operating expenditures.

“Utilities are going to respond to whatever mechanism the regulators put in front of them,” he said. “They have a fiduciary obligation to shareholders to maximize profits, and that’s what they’re going to do.

“It’s great for shareholders to replace [pipes]; it’s bad for ratepayers. If your state has an aggressive greenhouse gas target like Massachusetts does — net zero by 2050 — putting a pipe in the ground that’s going to last 50, 60 [or] 70 years does not make any sense.”

He said expedited cost recovery on the GSEP investments has removed the important check on utility spending that regulatory lag provides in traditional ratemaking. This lag between when utilities increase their spending and when rates go up “provides a strong incentive for the utility to control costs,” he said.

In April, the DPU lowered the cap on GSEP spending from 3 to 2.5% of total firm service revenues and indicated it will likely cut the cap to 2% in 2026 and 1.5% in 2027. The cap reduction, coupled with a ban on carrying charges, is intended to limit the amount of spending for which the utilities can receive expedited cost recovery. (See Mass. DPU Aims to Align Gas Leak Program with Climate Strategy.)

While questions about the obligation to serve could inhibit the use of non-pipe alternatives instead of traditional pipe replacements, “the vast majority of these projects aren’t even getting to that point of having conversations beyond just the internal utility screening,” said Jeremy Koo, assistant director of clean energy at the Metropolitan Area Planning Council, a regional planning agency representing municipalities in the Boston area.

He said there is “definitely a lack of transparency” around why utilities have ruled out repairs and non-pipe alternatives for GSEP projects.

“We’re really concerned about it from the perspective of stranded assets,” he said, noting that the utilities’ approach appears to entail increasing levels of investment in both the gas and electric systems, with ratepayers left with the costs.

He added that he is similarly concerned that lower-income customers who lack the means to exit the gas system will become saddled with an increasing share of the gas system’s growing fixed costs.

Separate but Related

The utilities’ increasing investments in pipe replacement bears more than a few similarities to growth of asset condition costs on New England’s electric transmission system.

Asset condition spending, which is aimed at upgrading deteriorating transmission infrastructure, has cost the region $4.67 billion for projects placed in service since the start of 2020, according to an October update from the region’s transmission owners.

Eversource and National Grid, which own the largest gas utility businesses in Massachusetts and two of the three largest electric transmission footprints in the region, are responsible for the vast majority — $4.2 billion — of asset condition spending since 2020. Asset condition investments are subject to limited regulatory scrutiny, passing to ratepayers through FERC formula rates.

Concerns about the spending have caused the New England states to make a big push for increased oversight and transparency into the projects over the past several years, and ISO-NE is establishing internal asset condition review capabilities that could provide information for potential challenges of the spending with FERC.

But at a recent event held by the Northeast Energy and Commerce Association, Rhode Island Public Utilities Commission Chair Ron Gerwatowski said this might not be enough. He said the states may need to consider changing how transmission costs are recovered through electric rates.

To reduce the TOs’ appetite for spending, he said, the states could introduce regulatory lag by requiring them to recover costs through the full base rate case process, instead of as pass-through costs.

Echoing Van Nostrand’s comments on gas pipe replacement spending, Gerwatowski said subjecting asset condition spending to regulatory lag “could give the financial folks an incentive to push back” on the investments. (See Facing Rising Demand, New England has Limited Options for New Supply.)

‘A Very Expensive Insurance Policy’

As regulators eye a managed transition away from gas, the future of the Everett Marine Terminal (EMT), an LNG import facility just north of Boston, remains a multimillion-dollar question mark. Similar to the GSEP program, questions about the gas utilities’ obligation to serve could have a major bearing on the terminal’s future.

The LNG facility is on the site of the Mystic Generating Station, a retired gas-fired power plant that was once its primary customer. The plant retired in 2024 at the end of a two-year reliability-must-run agreement with ISO-NE.

To keep the EMT in operation following the closure of Mystic, the Massachusetts gas utilities signed contracts with Constellation Energy, the owner of the facility, to keep the terminal open into 2030. (See Massachusetts DPU Approves Everett LNG Contracts.)

In the DPU’s approval of the contracts, it acknowledged the importance of the facility to ensure the reliability of the region’s gas system during peak days, but it directed the gas distribution companies to take action to reduce their reliance on the facility.

The EMT is located at a strategic location at the heart of the state’s gas system, has access to both the Tennessee and Algonquin pipeline systems, and can feed directly into National Grid’s distribution network.

“That was a tough decision,” Van Nostrand said. “Basically, it’s a very expensive insurance policy.”

Brattle Group consultants hired by the AGO estimated during the proceedings that the EMT contracts would cost a combined $946 million over their six-year span. (See Everett LNG Contracts Face Skepticism in DPU Proceedings.)

Gas customers in the state could face significant additional costs once the contracts expire if the utilities can’t eliminate their reliance on the facility.

Despite the regulatory requirements and a state-led working group focused on eliminating the state’s reliance on the facility, “another round of contracts seems incredibly likely,” said Carrie Katan, policy advocate at the Green Energy Consumers Alliance.

Katan, a member of the state’s Everett working group, said, “At this point, it does not look like either NSTAR [one of Eversource’s two gas distribution service territories] or National Grid are going to be able to basically function without EMT post-2030.”

A proposed expansion of the Algonquin pipeline system may cut some of Eversource’s reliance on Everett. The company’s recently approved firm transportation agreements associated with the expansion project would eliminate the need to extend the Everett contract for one of its service territories and partly eliminate the reliance on the terminal for its other service territory, Eversource wrote (DPU 25-133, 25-134).

But eliminating reliance on the terminal in one service territory could result in shifting the facility’s significant fixed costs onto gas customers in other areas still reliant on it.

It is also unclear what Constellation might charge to keep it open past 2030.

“Constellation is not operating on any kind of cost-of-service agreement: They can charge whatever price they want, and if they wanted to shut down EMT whenever they decided to, they could do that,” Katan said.

Van Nostrand concurred: “The LDCs put themselves in a position where they’re pretty much at Constellation’s mercy.”

Katan said National Grid appears to be in the “weakest negotiating position,” adding that “it really does seem to me that [Constellation] could decide to squeeze National Grid as hard as possible, and I don’t know of anything National Grid can do.”

National Grid declined to comment on whether it expects to seek additional contracts with Constellation. It said in a statement that its “responsibility is to operate a safe, reliable gas system for the customers who count on us, which requires making the investments necessary to keep aging infrastructure secure.”

Eliminating reliance on the Everett facility would require “a number of interventions, which would take a large amount of time,” such as strategic electrification or a moratorium on new gas hookups in EMT-constrained areas, Katan said.

But the utilities’ insistence that they cannot decommission lines without the consent of all customers complicates the picture.

While neighborhood-wide networked geothermal heating systems had drawn significant attention in the state in recent years, including pilot projects run by Eversource and National Grid, “if you want to deploy networked geothermal on a large scale outside of the pilots, you’re going to have to decommission the gas lines,” Katan said.

If the state cannot decommission pipes, “I don’t think we have anything when it comes to controlling gas costs,” she said. “I think at that point you would just need to accept that the situation is bad, it will get worse, and there is absolutely nothing that can be done about it.”