State officials pursuing offshore wind projects said last week they are happy with support from the Biden administration but need additional federal help on transmission planning and designing clean energy markets to support the infrastructure.

Officials from Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York and Virginia spoke on a panel at the Reuters U.S. Offshore Wind 2021 conference, two weeks after the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management gave final approval for the Vineyard Wind project, which had been delayed by the Trump administration. The approval made the 800-MW Vineyard Wind I the first commercial-scale offshore wind project to win approval in the U.S.

“It’s a whole different ball game at the federal level now than it was two or three years ago,” said David Lehman, commissioner of the Connecticut Department of Economic and Community Development.

“There’s a ton of momentum here,” agreed Tim Sullivan, CEO of the New Jersey Economic Development Authority. “There’s going to be a North American, North Atlantic offshore wind energy patch that creates a regional industry of great consequence, in a way that fossil fuels have done for the Gulf [of Mexico]. The [potential] from a job creation perspective is extraordinary.”

But Kathleen Theoharides, secretary of the Massachusetts Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs, said long-term transmission planning will be necessary for offshore wind to succeed and states to meet their clean energy targets. “That need is arguably the most significant barrier to offshore wind buildout in the region and has been a real focus for Gov. [Charlie] Baker and our energy team,” she said. “Guidance from FERC to the regional ISOs around the country around the design of clean energy markets and transmission planning is a key piece where the feds could step in and be very helpful.”

John Warren, director of the Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy, said inadequate transmission could increase financing costs. “I see a scenario where our ability to make generation infrastructure far outpaces our ability to distribute the generation,” he said. “It’s almost like we’ve gotten really good at building cars, but we don’t have enough roads to drive them on. When it reaches that tipping point, it could impede the further growth and the momentum.”

Doreen Harris, CEO of the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority, said states pursuing OSW are “grappling with [the] need to walk and chew gum at the same time. … We cannot pause our generation projects and the infrastructure and the investments that we’re all making to wait for coordinated transmission to emerge and be available. But there are smart ways to do both in parallel. … I see them as two lanes that will travel in parallel and eventually merge. That’s really what we are doing when we look at transmission planning.

“These are …. incredibly complex projects to advance, but they are indeed necessary for the ultimate buildout on the scale that we are looking at,” she continued. “It’s one of the reasons that New York is looking at emulating some of the mesh transmission solutions utilized in Europe, because it allows us to move our projects forward and ultimately build the grid … as the projects are built themselves.”

Lessons Learned

Theoharides also shared the lessons learned in Massachusetts, which has conducted three OSW procurements since 2018.

“One strategy we’ve used … is giving us enough time between procurements so that our Department of Energy Resources can continue to refine our procurement process. And we’ve done that since the first project was selected.”

After the Trump administration delayed approval of Vineyard Wind’s permit in 2019, Theoharides said, “developers put in much [longer] timelines for going through the federal permitting process.”

She said the state had benefited from feedback from a wide range of stakeholders, including fisheries, wind developers and environmental justice communities.

“For example, the [request for proposals] issued earlier this month for the third solicitation now allows [proposals of] 200 to 1,600 MW — doubling the [size] of the previous solicitation — consistent with findings … that by allowing larger-size bids, we could capture some potential efficiencies related to cabling [and] the use of [on-land] connection points.

“For our latest RFP … we’ve made significant revisions to strengthen criteria regarding impacts and benefits to environmental justice communities,” she added.

Connecticut’s Lehman asked whether the states might obtain lower prices from developers by conducting joint procurements. “I think that’s a possibility and something we’d be eager to discuss in Connecticut,” he said.

“We are very interested in regional procurements in Massachusetts,” Theoharides responded. “And we have been talking to our legislature about including that in future” procurements.

30 GW by 2035?

Before the state officials’ panel discussion, the conference heard a presentation from Imogen Brown, the head of BloombergNEF’s offshore wind research, who predicted fast growth in the U.S. — but not fast enough to reach Biden’s target of 30 GW by 2030.

Global OSW is likely to grow from 36 GW in 2020 to 206 GW in 2030, a 19% compound annual growth rate, she said. The surge will be led by China, the U.K., Germany and the U.S., the last of which will have 24 GW by 2030, she said.

“This is significant growth from where we are — almost at nothing — today. And we expect the U.S. by 2030 to account for about 11% of the offshore wind market.”

Bloomberg expects the market to “get kickstarted around 2024” with Vineyard, the 1,100-MW Ocean Wind project off New Jersey and 704-MW Revolution Wind off Rhode Island.

“If you compare it to a market like the U.K., which is very well established — it has been commissioning offshore wind projects for decades … essentially the U.S. is skipping this ramp-up period. It’s going big and going big quickly. If you compare it to Germany, it looks about double Germany’s installations across the second half of the decade.”

Bloomberg predicts the U.S. will add about 3 GW of OSW annually from 2025 to 2030, short of the 5-GW average needed to reach the 30-by-2030 goal.

“We view the U.S. offshore wind market as a very state-led game; they’re the ones that are procuring offshore wind capacity. And they’re the ones that are setting targets,” Brown said.

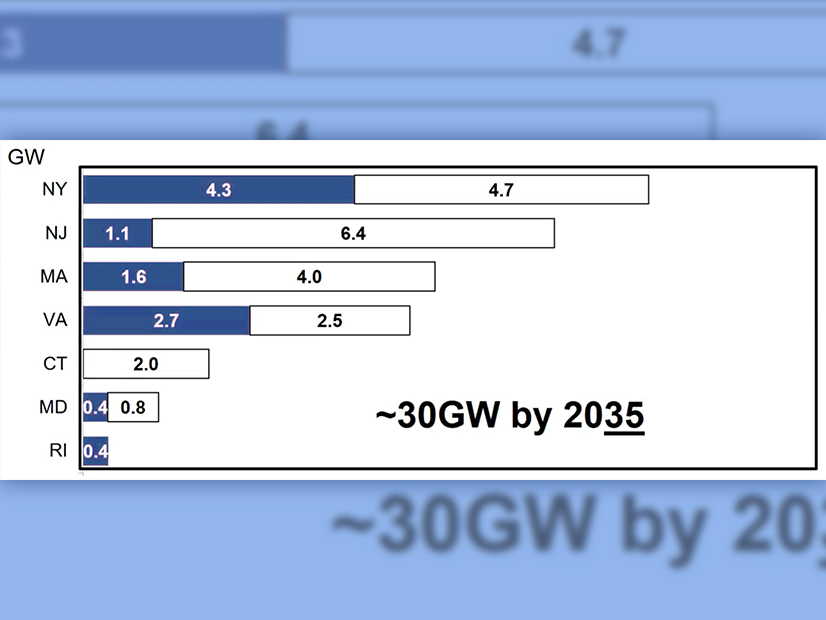

The states driving currently driving OSW are New York, with a target of 9 GW; New Jersey (7.5 GW); Massachusetts (5.6 GW); Virginia (5.2 GW); Connecticut (2 GW); Maryland (1.2 GW); and Rhode Island (400 MW).

Bloomberg conducted an assessment to predict which states might be next to join the OSW trend, evaluating factors including resource potential, power prices, onshore wind saturation and renewable energy policies. Based on all the criteria, it ranked California top in the “next phase markets,” followed by New Hampshire, Maine, Oregon and Hawaii.

Delaware, Ohio, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Washington, Illinois, Texas, Louisiana and South Carolina were ranked lower as “potential markets.”