By Rich Heidorn Jr.

NEW YORK — Looking for a place to assemble offshore wind farms on the East Coast?

New York officials say their 63 acres at the South Brooklyn Marine Terminal could be just the place. For about $300 million, a report for the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority says, it could demolish existing warehouses, dredge the dock area and fortify the ground to withstand loads of 6,000 pounds/square foot to dedicate the port to OSW staging and deployment.

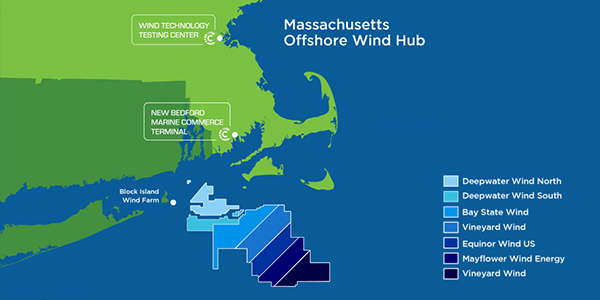

Massachusetts officials, meanwhile, are touting New Bedford, insisting the new industry can coexist with fishermen in the most productive fishing port in the country. In October, developers signed a lease to use the New Bedford Marine Commerce Terminal to stage and construct turbines for the 800-MW Vineyard Wind project 15 miles south of Martha’s Vineyard.

And Boston office buildings are renting space to members of the European OSW industry looking to create a headquarters for their U.S. operations.

East Coast states are now promising to fund the construction of nearly 18,000 MW of offshore wind, almost equal to Europe’s current capacity. While state officials say the procurements are long-term investments intended to address climate change, they acknowledge the immediate lure is economic development. The European OSW industry employs 40,000 people.

At the Business Network for Offshore Wind’s 2019 International Partnering Forum at the Grand Hyatt New York last week, the talk was all about the jobs and contracts the industry would bring. In the forum’s exhibit area, state economic development agencies and labor unions manned booths alongside engineering firms and providers of everything from cranes to helicopters to drones.

Liz Burdock, CEO of the Business Network, said that while building a local supply chain will lower the cost of U.S. OSW, it is the economic development that the industry should promote in talking with other stakeholders.

“As we talk about public acceptance and getting more people willing to support our industry, I don’t think it is really about what is the lowest cost of energy. It has to be about what is the job creation. And maybe we are going to have to pay a little bit more,” she said. “I think that’s something that we need to start saying.”

“We have every intention to be here locally,” said Jason Folsom, director of U.S. sales for MHI Vestas Offshore Wind, a joint venture between Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and turbine maker Vestas Wind Systems based in Denmark. “We do not want to run our new market businesses from Europe. We’re here to build stuff.”

Cooperation vs. Competition

Numerous speakers at the conference questioned whether states can cooperate to nurture the fledgling industry even as they compete to promote their ports as potential manufacturing hubs. Several urged states to stagger their procurements to create steady, predictable demand.

“The supply chain in the U.K. was really dependent on having consistent procurements happening,” said Eric Thumma, director of policy and regulatory affairs for Avangrid Renewables. “When they had an on-again, off-again nature of the procurements, that made it very difficult to get supply chain folks to be confident enough to invest. So, one of the challenges in the U.S. is how do you get the states to collaborate on sort of a comprehensive offshore policy?”

NYSERDA Chairman Richard Kauffman said the states are cooperating through the National Offshore Wind Research & Development Consortium, which the agency started last year with funding from the U.S. Department of Energy. Other participants include the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Brookhaven National Laboratory, developers, and the states of Maryland, Massachusetts and Virginia.

“We frankly never realized the power of friendly competition that we started through this collaboration,” Kauffman said. “All Eastern states with water can benefit from scale.”

NYSERDA CEO Alicia Barton was asked by an audience member during one panel discussion at the IPF whether New York would invest in assets outside the state if it can’t build a manufacturing hub in any of its ports.

“We get that question a lot,” she acknowledged, without definitively answering it. “I work for the people of New York, and I am, along with Gov. [Andrew] Cuomo, committed to making New York the center for the U.S. offshore wind industry. We’re not shy about that.

“On the other hand, we are quite realistic. … We want 9,000 MW of offshore wind. That makes us a very large buyer of offshore wind, locally speaking. … It is without a doubt in our interests to see the U.S. supply chain mature [and] develop as fast as possible to see the U.S. industry scale as fast as possible so that as a large buyer, we will get the best deal possible.”

Tim Sullivan, CEO of the New Jersey Economic Development Authority, said he’s realistic. “We’d love to have those 40,000 [jobs] in New Jersey, but it’s going to be a regional thing,” he said.

Sullivan said states will need to work with community colleges and labor unions to develop the workforce needed to ensure the supply chain is developed locally. “Cobbling together wind, offshore wind and oil and gas [resources] from the European supply chain … would be a really unfortunate outcome,” he said. “That would be a terrible outcome for New Jersey … for the Northeast, because this is a once-in-a-generation opportunity.”

Sullivan said officials overseeing port development for OSW also need to balance short- and long-term considerations.

“There will be an impulse to overly design the infrastructure and the supply chain to [accommodate] the first set of projects that are moving forward as opposed to designing for an industry,” he said. “We want a network of ports that is somewhat project-agnostic, that is somewhat developer-agnostic, so it can have multiple users over the next 45 to 50 years.”

Walter Cruickshank, acting director of the U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, which awards leases and oversees OSW projects in federal waters, said his agency is doing its part to ensure the industry’s growth by developing “an efficient and predictable regulatory process.”

BOEM has issued 15 leases totaling more than 1.7 million acres at a cost of almost $477 million since 2012. The lease price per acre — which had been as low as $39 in 2013 — topped $1,000 in three auctions off Massachusetts last year.

Cruickshank said OSW projects will be subject to President Trump’s “one federal decision” executive order, which requires all federal agencies to coordinate their reviews of major infrastructure projects in a single proceeding and to issue rulings within two years.

BOEM also is taking a regional approach to its evaluation of some potential new wind energy areas (WEAs), he said.

Rather than focus on the small section of the ocean off New Hampshire’s narrow 18.5-mile coast, he said, “We see value in looking at the Gulf of Maine as a whole, and pulling in the states of Maine and Massachusetts to look … at the effect of sharing natural, socioeconomic and cultural resources to plan how we might proceed in that area.”

BOEM also is combining the planning processes for the Carolinas, with plans to identify a WEA there later this year.

Giles Dickson, CEO of WindEurope, a trade group representing the European wind industry, said success for the U.S. OSW industry will require “happy coexistence” with the military as well as the fishing and shipping industries.

NYSERDA was cognizant of those stakeholders when it issued a solicitation for the state’s first, 800-MW OSW procurement, Barton said. The agency is expected to announce the winners next month. (See Four Bidders Vie for NY Offshore Wind Project.)

“We made clear … that we wanted to see great projects,” Barton said. “That we wanted to see strong economic development commitments, that we wanted to see commitments to labor … we wanted to see fishery mitigation plans.”

100% Clean

The Atlantic states’ OSW targets are central to their efforts to reduce carbon emissions and address climate change.

In January, for example, Cuomo announced New York was nearly quadrupling its offshore wind energy goal to 9 GW as part of its plan to reach “100% clean power” by 2040. (See New York Boosts Zero-carbon, Renewable Goals.)

New Jersey, California, Hawaii, New Mexico, Puerto Rico and more than 100 cities across the country have also pledged to move to 100% renewable or “clean” energy, as have more than 150 companies, from Adobe to Walmart.

While the 100% goal has no shortage of critics who question its feasibility, those who support it say OSW will be a big part of the resulting generation mix. A recent Stanford study projected a 19% share for offshore wind, with onshore wind and utility-scale PV at 31% each.

“It’s very ambitious, but we do believe it’s actually achievable,” Barton said of Cuomo’s goal. “To achieve that target, offshore wind has to be a huge piece of the puzzle,” she added, noting that the 9,000 MW of OSW would represent 30% of the state’s load.

Barton said the 100% pledges by Cuomo and other governors reset “the conversation about what’s possible. Even a year or two, three years ago, we would not be talking about California, New York [and] New Jersey — major economies in the U.S. — committing to a 100% clean electricity. It’s been a radical mind shift. It’s clear we don’t have a lot of time … to do what we know needs to be done to combat climate [change].”

Marie Hindhede, deputy permanent secretary for the Danish Ministry of Energy, Utilities and Climate, said higher penetration by renewables doesn’t mean less reliability, noting her country had 99.99% “security of supply” despite getting three-quarters of its power from wind, solar and biomass.

To reach the 100% goal, she said, Denmark needs an active demand-side response and more transmission to sell power across national boundaries. Hindhede said power trading with other countries has been key to balancing intermittent generation thus far but that electric storage will likely be part of the solution in the future.

Steve Dayney, head of North American offshore operations for Siemens Gamesa Renewable Energy, said reaching 100% is “not really an issue of technology. It’s an issue of, do we have the will to do it? It’s an issue of how fast new technologies can emerge and how quickly can we industrialize it to make it cost-competitive.”

Ditlev Engel, CEO of DNV GL, which provides risk management and quality assurance services to OSW and other maritime energy industries, said one key to winning political support for 100% policies is to include the health-related costs of climate change and air pollution in the discussion.

“Everybody talks about the cost of electricity per megawatt or per kilowatt-hour. But what about the costs to society? Are we using the right rulers for how we set the systems up?” he asked.