Implementing Virginia’s ambitious environmental justice goals could cost the state millions of dollars and require hiring dozens of new full-time employees, as well as consultants, according to a new report from the Interagency Environmental Justice Working Group.

The 44-page report did not specify a dollar amount, but a majority of the 35 state agencies covered in the study said additional funding and time would be needed for them to create and implement robust environmental justice policies. An estimated 34 new full-time positions spread over 24 state agencies would also be required, the report said.

“This report represents an important first step towards securing justice for disadvantage communities that have been disproportionately burdened by the impact of climate change,” Gov. Ralph Northam said in a statement released with the report.

The report and the formation of the working group were mandated as an addendum to Virginia’s Environmental Justice Act, signed into law by Northam last year. The law calls on state government to incorporate environmental justice considerations into policy and decision making affecting low-income and disadvantaged communities.

Some of the report’s key findings included:

-

-

- Six agencies identified a need for internal assessments of environmental justice-related regulations and policies to develop a baseline level of understanding, including the Virginia Marine Resources Commission, Department of Wildlife Resources and Department of Historical Resources.

- Six agencies also reported they would need a third-party consultant to complete an environmental justice study, including the Office of the Secretary of the Commonwealth and Virginia Economic Development Partnership.

- Each agency assessment will cost between $50,000 and $100,000, and some agencies reported they would need more than two years to comply with the law.

-

The law defines environmental justice as “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of every person, regardless of race, color, national origin, income, faith or disability, regarding the development, implementation or enforcement of any environmental law, regulation or policy.”

The working group included top officials from about a dozen state agencies and the governor’s office. The group met four times in October and November 2020 to produce the report, assessing each agency on environmental justice performance in policy and regulations, community engagement and involvement, economic development and infrastructure, and fiscal impact and resources.

Checking Boxes

Based on the report, different state agencies are clearly at different points in their awareness and action on environmental justice issues. The Department of Wildlife Resources, for example, said that while it hired a director of diversity and inclusion in 2018, it “does not have agency-specific environmental justice policy currently in place”; nor has it done a full analysis of the policies and regulations that would be needed.

Meanwhile, the Department of Transportation, the state’s largest agency, does have environmental justice guidelines to provide its various divisions “with a consistent framework for both preparing an EJ analysis and developing an effective public involvement strategy.” However, actual implementation across the department is uneven.

The Department of Environmental Quality is farthest along in its efforts. The agency hired an outside consultant in 2019 to produce a study and recommendations on how to incorporate environmental justice principles into its planning and programs.

In the report the department says, “Success in advancing environmental justice through DEQ’s activities won’t simply involve ‘checking boxes,’ but rather putting a process in place to build trust, share understanding and align values among community members, stakeholders, local state and federal government, industry partners and DEQ staff.”

State-level Action

The report’s primary recommendation is to make the working group an ongoing body with public hearings in which it can gather input from environmental justice communities. The group would work with the Virginia Council on Environmental Justice and the Office of Diversity, Equality and Inclusion, and continue to produce annual reports on the state’s environmental justice performance.

“While an environmental justice assessment is not applicable for every Virginia state agency, the continuation of collaboration across state agencies, with leadership by environmental protection agencies, is beneficial to the continued progression of environmental justice policy in the commonwealth,” the report says.

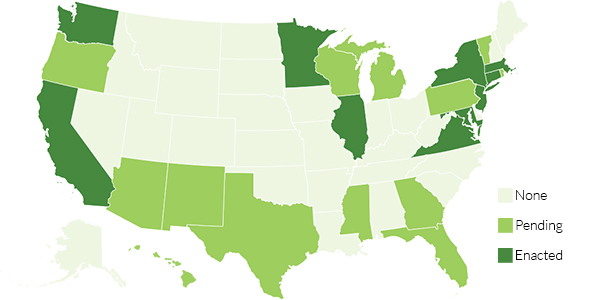

Virginia is one of a growing number of states that have either enacted or are considering environmental justice laws. According to a recent analysis by Bloomberg Law, environmental justice statutes are on the books in 10 states and pending in 13. On the federal level, President Biden’s executive order on climate change included a Justice40 provision, requiring 40% of all benefits from government investments benefit disadvantaged communities, with results tracked on an Environmental Justice Scorecard. A federal Environmental Justice for All Act was introduced in the House in 2020 but never got beyond committee hearings.