Three-quarters of economists who study climate issues say “immediate and drastic action” is needed to address climate change, according to a new survey, a 50% increase over a similar survey in 2015.

The biggest reason for the increase: “extreme weather events attributed to climate change.”

The economists also predicted climate change will hurt the economy and worsen income inequality, and said efforts to mitigate change would be cheaper than dealing with the effects of it.

The New York University School of Law’s Institute for Policy Integrity heard from 738 economists out of the 2,169 invited to participate — all of whom had published articles on climate in 45 top-rated economics, environmental economics and development economics journals — for a response rate of 34%.

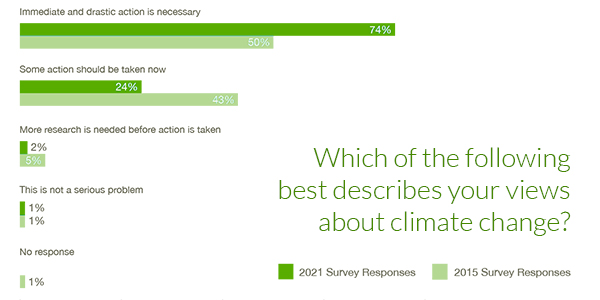

In IPI’s 2015 survey, involving 365 economists, only 50% thought immediate and drastic action was needed.

The new survey found 74% favoring immediate action and another 24% agreeing “some action should be taken now,” with 2% calling for more research before taking action and 1% saying climate change is “not a serious problem.”

“People who spend their careers studying our economy are in widespread agreement that climate change will be expensive, potentially devastatingly so,” said Peter Howard, economics director at the institute, who co-authored the study. “These findings show a clear economic case for urgent climate action.”

About 41% of respondents said their concern over climate change had “strongly increased” over the past five years, with another 38% saying it had “somewhat increased.”

Asked to identify up to three factors that most affected their views on climate change in recent years, the most common answer, selected by 52% of respondents, was “observed extreme weather events attributed to climate change.”

New findings in climate science (31%) and new findings in climate economics and the social sciences (29%) also were widely cited.

“These empirical observations of climate impacts appear to have had an outsize role in shaping economists’ views, perhaps due to the high level of damage caused by recent extreme weather events (such as wildfires in Australia and the Western United States, heat waves in Europe and historically large numbers of hurricanes),” wrote Howard and Derek Sylvan, the institute’s strategy director. “Such events may also have stood out to economists because many projections anticipated that the current levels of temperature increase and climate-linked extreme weather would take longer to manifest than they have. … Extreme weather events also frequently elevate the general public’s level of concern about climate change.”

There also was consensus that climate change will hurt economic growth (42% calling it “extremely likely” and 36% calling it “likely”) and that it was likely to increase income inequality between the richest and poorest countries (89%). Seven in 10 said it was also likely to increase inequality within countries.

The good news? Almost two-thirds expect emerging zero-emission and negative-emission technologies to experience the kinds of cost declines seen in wind and solar generation.

Asked what percentage of the global energy mix will be zero-emission technologies (e.g., solar, wind, nuclear, green hydrogen, bioenergy, and carbon capture and storage) by 2050, the median response was 50.5%. Zero-emission sources are currently 10% of the energy mix, according to the International Energy Agency.

About half of the economists said they expected net-negative greenhouse gas emission technologies, such as direct air capture and carbon capture/utilization/storage to become reliable and cost competitive for large-scale adoption by 2060, with about 12% expecting a role by 2080. More than 5% said the technology will never work at scale, and “roughly 25% of respondents chose the ‘No Opinion’ option, suggesting a high level of uncertainty for this question,” the authors wrote.

Most scenarios for limiting temperatures to 1.5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels assume wide use of negative-emissions technologies by midcentury, the authors noted.

But they said the optimism of the economists “should be tempered somewhat, as engineers and other categories of experts may have equally (or more) relevant insights on these issues than economists, and their views may differ. Many researchers who focus on the energy transition advise a ‘precautionary approach’ with respect to negative-emissions technologies, given that they are unproven and overreliance on these technologies could deter necessary emissions reductions in the near term.”

The median of the economists’ projections predicted that economic damages from climate change will hit $1.7 trillion annually by 2025 (with a 1.2-C increase over pre-industrial levels) and about $30 trillion per year — at least 5% of GDP — by 2075 (+3 C).

Two-thirds of the respondents said the benefits of reaching net-zero GHG targets by 2050 is likely (35%) or very likely (31%) to outweigh the expected costs. Almost one in five said the cost-benefit was unclear, while 12% said benefits were unlikely to outweigh costs.

The 15-question survey did not ask the economists about potential policy solutions, such as spending on research or imposing carbon fees. But the authors said the “consensus views of economists with expertise on climate change can provide valuable insights for policymakers who must weigh the benefits and costs of various climate strategies.”

The authors cited criticism of integrated assessment models (IAMs) used to estimate the social cost of carbon (SCC), which is used in federal government cost-benefit analyses.

“IAMs and the results derived from them, including the SCC, are highly sensitive to modelers’ assumptions, which do not necessarily reflect the consensus views of experts,” the authors wrote. “Research based on our 2015 survey shows that when an IAM is recalibrated to use the discount rate and damage function preferred by respondents to an expert survey, the SCC value increases more than tenfold. …

“The Biden administration is currently conducting a review of the climate impact modeling used by the U.S. government, and these survey results could be used to help recalibrate some key model parameters.”