As North Carolina considers whether to join the 11-state Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI), a new report says participation in the 11-state carbon market could be critical for the state in reaching its goal of cutting carbon emissions 70% by 2030.

The study from researchers at Duke University and the University of North Carolina also identifies a menu of additional policy options, such as adopting a clean energy standard, accelerating coal plant retirements or charging polluters a premium for carbon emissions.

In January, Clean Air Carolina and the North Carolina Coastal Federation filed a petition with the state’s Department of Environmental Quality to join RGGI. The petition, now with the DEQ’s Environmental Management Commission, is under review, said Sharon Martin, DEQ deputy secretary for public affairs.

But the Duke-UNC study avoids recommending RGGI or any emissions-reducing policy as the most effective. After extensive stakeholder input, the authors learned that people were concerned about the divisiveness that could arise over endorsing a single policy.

“We realized there were multiple paths forward that were cost-effective and impactful, so boiling it down to one policy didn’t make a lot of sense,” said Kate Konschnik, director of the Climate and Energy Program at Duke’s Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions and one of the study authors. “We figured the best thing we can do here, given that there isn’t just one silver bullet, is provide a suite of options to the governor and be really transparent about the different outcomes.”

A primary finding of the study is that the electricity system in North Carolina is at a tipping point between gas and renewables.

“The prices of clean energy resources like wind and solar are coming to a convergence with coal and gas right now,” said Michelle Allen, project manager for North Carolina political affairs at the Environmental Defense Fund. “If we have some sort of carbon reduction policy in place, it will help to drive clean energy sources on to the grid.”

Konschnik highlighted a second potential tipping point: As gas prices rise in the 2030s, dual-fired coal and gas units might go back to burning coal under a business-as-usual scenario.

“This was concerning because we really thought that it was just going to be the difference between prices of renewables and gas in thinking about new capacity,” she said. “But in some of these dual-fired facilities, there could be a relaxing back into coal if gas prices went up sufficiently.”

Policy Combinations Lead to Greatest Emissions Reductions

Of the roughly three dozen recommendations made in North Carolina’s 2019 Clean Energy Plan, conducting this study on how to decarbonize the power sector was at the top of the list.

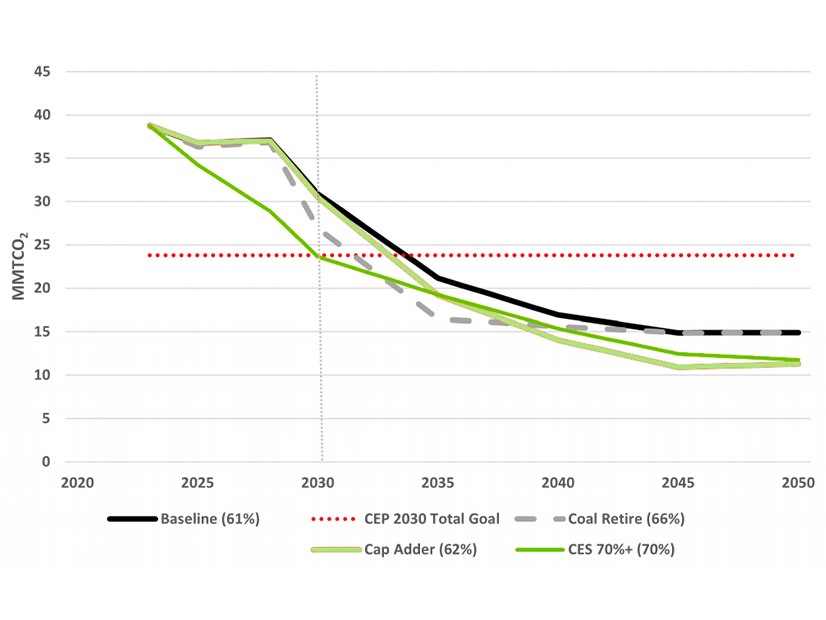

Using two models, one common to the electric utility world created by the consulting company ICF and another developed at the Duke Nicholas Institute, the authors analyzed the cost, emissions, generation mix and pollution outcomes of specific policies against a “business-as-usual” scenario of least-cost supply with no new clean energy.

Under a business-as-usual scenario, neither model could reach the 2030 goal without additional policies. However, in the Nicholas Institute model, two standalone policies met the 70% reduction target: a premium price on carbon emissions from generation, called “carbon adders,” and a clean energy standard (CES) that would either set increasing goals for clean energy or decreasing levels for carbon emissions.

Other policies, such as RGGI or carbon adders, layered on a CES could also meet the 2030 goal, the report said. But, the two most cost-effective options, with less than a 1% cost increase, were coal retirements and joining RGGI.

The models also evaluated policies based on air pollution reduction, an important consideration for equitable policy design, the study said. Two pollutants, sulfur dioxide (SOx) and nitrogen oxides (NOx), both known to cause respiratory damage, were analyzed. Accelerated coal retirements significantly reduced both pollutants in the short term, the study found.

Looking to 2050, Konschnik said that none of the policies modeled get North Carolina to net zero. All of the policies and combinations reach about a 90% reduction in emissions below 2005 levels, relying on future technology to fill that gap. What’s important, Konschnik said, is which policies will best set up the state for that future.

RGGI Found to be Cost-effective, Reliable and Equitable

“RGGI has successfully, affordably and equitably shown it can cut emissions,” said Joel Porter, policy manager for Clean Air Carolina, talking about the organization’s petition to the DEQ. “Not only do market mechanisms work, but they can benefit the economy as well. It was a no-brainer for us to submit the petition.”

Part of RGGI’s appeal, Allen said, is that it would put the state on a predictable trajectory of emissions decline. And as with the CES, stacking other policies on top of RGGI participation could further speed up emissions reductions, she said.

In the 11 Northeast and Mid-Atlantic states where RGGI has been implemented, “participants have seen about a 49% reduction in their emissions over the past 10 or so years,” Allen said. “It’s a proven program that’s effective over a certain time frame.”

RGGI is also surprisingly cost-effective. Allen said that if RGGI were implemented in North Carolina and the revenue from the program were reinvested into energy efficiency, “it was the only stand-alone policy of all analyzed that actually produced an overall cost savings compared to a business-as-usual scenario.”

In addition to reducing NOx and SOx pollutants, joining RGGI could get money back to communities, Porter said. For example, he said in an email to NetZero Insider, the North Carolina Utilities Commission could require Duke Energy to send the money it would have otherwise spent on emission permits back to ratepayers.

After the 120-day comment period, if the commission decides to initiate rulemaking, the petition will go to the General Assembly, where Porter thinks the legislature will likely pass a resolution of disapproval. But Porter hopes that with Gov. Cooper’s track record of climate action, he will veto the resolution, making RGGI law. The governor’s office did not respond to requests for comment.

From Results to Action

Beyond rulemaking within the DEQ, Konschnik and Allen see avenues for legislation. “There’s an expectation that there will be some electricity sector legislation this year,” Konschnik said. “What that looks like, we’re not clear yet.”

While the study incorporated information from Duke Energy’s integrated resource plans, Konschnik said that the research team didn’t use the IRPs modeling, as the study covers all of North Carolina, not just Duke customers. She also said that the high carbon reduction pathways in the IRPs do not constitute a policy, since the plans don’t detail the regulatory changes that would be needed to implement these pathways.

Yet, the IRPs are still important to consider in the bigger picture of decarbonizing North Carolina’s power sector, Allen said, as they “set out the path that our utilities will take in terms of what sort of generation will be on the grid and how they’re going to deploy those resources.”

Since Duke filed its IRPs in September, the plans have been met with opposition from a variety of stakeholders, including local governments, tech corporations and environmental justice groups. Many critiques argued that Duke’s IRPs were too reliant on natural gas in the future instead of investing in renewable generation, which Duke claims are cost-prohibitive at this time. In the six pathways that Duke presented, only one did not include any new fossil fuel generation. There were a record-number 211 requests to speak at the upcoming North Carolina Utilities Commission hearings on the IRPs, forcing the commission to split the hearing into six sessions, the first of which will be held on Wednesday. The others are scheduled throughout April and May. (See NC Net-zero Goals Could Hinge on Duke IRPs).

“Marginal coal retirements alone aren’t going to achieve our long term pollution reduction needs,” Allen said. “That’s why we need some of these additional policies like joining RGGI or implementing a clean energy standard that will driver deeper and faster reductions in emissions and put more clean energy on the grid in a timescale that we need.”

Since the report was released, Konschnik has seen rising interest in its findings from state and local policy makers. The study authors have briefed the Governor’s Climate Council, other government agencies and a collection of North Carolina cities, among others. But beyond these presentations, Konschnik said, there “wasn’t any sort of official trigger that happened as a result of publishing this report” in terms of follow up or further actions by DEQ or the legislature.

Allen said the ball is in the policymakers’ court. A big takeaway, she said, is it’s “not necessarily choosing one policy or the other, but how do we stack these policies on top of each other in order to get the most benefits and the most cost-effective pollution reduction that we can while also investing in our economy.”