California’s cement industry is committed to reaching carbon neutrality by 2045, but a recent trade association report shows that the process won’t be easy.

One challenge is the “immutable” emission of CO2 that comes from a chemical reaction during the cement manufacturing process, according to the California Nevada Cement Association. As a result, total decarbonization would require carbon capture and storage, expensive technology the industry would need help paying for, CNCA said.

The industry could also reduce greenhouse gas emissions by changing the formulation of cement or switching from coal to other fuels used during the manufacturing process. However, barriers including statutory, regulatory and permitting hurdles make those steps more difficult, the nonprofit trade association said.

CNCA issued a report in March that outlines how the cement industry can attain carbon neutrality.

“Releasing this industry-wide roadmap is an exciting and critical step toward carbon neutrality,” CNCA Executive Director Tom Tietz said in a news release at the time. “However, we cannot get to net zero alone, and this roadmap is also an invitation for state leaders, environmental groups and stakeholders throughout the cement-concrete-construction value chain to collaborate on pursuing this bold goal.”

GHG Contribution

Cement is a key component of concrete, which is the most widely used building material in the world.

The cement industry is responsible for about a quarter of all CO2 emissions from industry, according to a report last year from McKinsey & Co.

And recognition of cement’s contribution to greenhouse gas emissions is growing.

“Pressure for the cement industry to decarbonize has increased rapidly, not only from society but also investors and governments,” the McKinsey report said. The report recommended many decarbonization strategies that are similar to those included in the CNCA report.

In California, cement production accounted for 1.8% of GHG emissions in 2017, according to the California Air Resources Board.

The issue has caught the attention of state lawmakers, who have introduced bills aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions from concrete. (See Calif. Bills Seek to Decarbonize Concrete.)

Cement Production Process

Cement manufacturing involves the production of “clinker,” a substance made by heating limestone and clay in a rotating kiln to about 2,700 degrees Fahrenheit. Clinker is then ground and mixed with limestone and gypsum to make what is known as ordinary Portland cement.

To make concrete, cement is mixed with water, sand and an aggregate such as gravel.

Clinker production accounts for most of the greenhouse gas emissions from cement manufacturing, according to CNCA. About half the GHG emissions are from the chemical reaction that occurs when limestone is heated. Another 40% is from energy used in the heating process.

CNCA said the industry faces an “extreme challenge” in reducing so-called process emissions that are produced during the limestone heating process. As a result, investments in carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) are necessary, the group said.

In addition to the public investment that’s needed for the high-priced CCUS technology, CNCA said regulatory barriers need to be reduced. The group pointed to the sometimes years-long process for federal and state environmental review of the projects.

“In short, carbon neutrality is out of reach for the cement industry in the absence of measures that would enable more aggressive deployment of CCUS,” the report said.

Reformulating Cement

Still, some GHG reductions can be achieved by reformulating cement to reduce the ratio of clinker, CNCA said.

For example, Portland limestone cement (PLC) has an extra 10% of limestone added compared to ordinary Portland cement (OPC), which reduces production emissions by up to 10%. The modified formula doesn’t affect the cement’s performance, CNCA said.

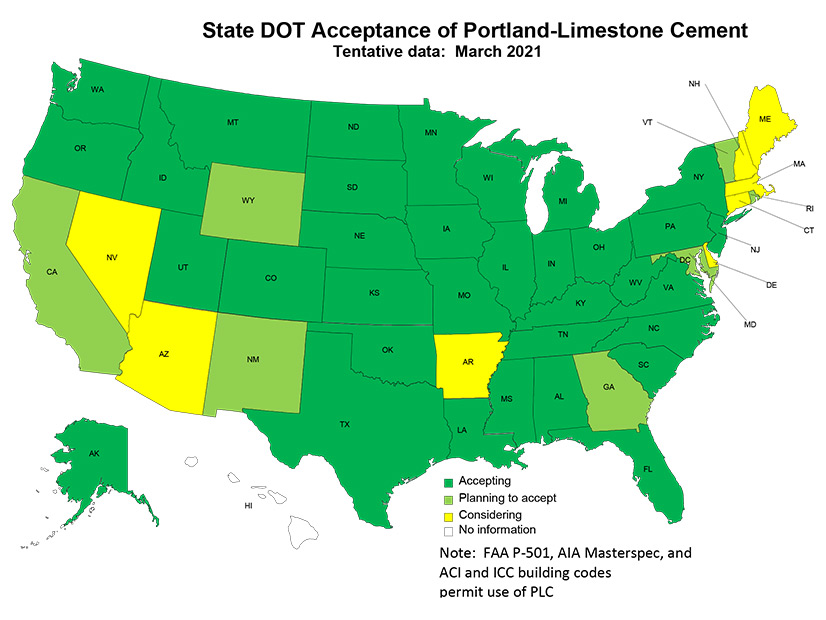

But some state transportation departments have not yet accepted PLC. In California, PLC “is currently not accepted for Caltrans-specified construction projects,” CNCA said.

“Given that a significant share of all cement produced in California is specified for Caltrans or local governments for use in roads and sidewalks, its adoption of PLC standards is a key driver of PLC production in California,” CNCA said in its report.

A Caltrans spokesman didn’t immediately provide information on Friday about the agency’s acceptance of PLC.

Another strategy for reducing process emissions is to substitute a portion of the clinker that goes into cement with another substance. CNCA said some of the possible alternative materials are fly ash and ground granulated blast furnace slag.

Alternative Energy Sources

Another approach to decarbonizing cement would be to switch from coal to other energy sources to produce the heat needed to make clinker.

Replacing coal and pet coke combustion with natural gas would reduce emissions by about 15%, CNCA said. But the group said natural gas is not usually cost-competitive with coal for California cement plants.

“Natural gas prices in California, particularly for industrial users, remain well above the national average thanks to statewide storage and supply constraints,” CNCA said.

Waste-derived fuels, such as engineered municipal solid waste or fuel made from discarded tires, are other options for the cement industry. But regulatory and statutory barriers make switching to waste-derived fuels difficult, CNCA said.

For example, even though California has a goal of reducing solid waste by 75% through reducing, recycling, or composting, using the waste as fuel doesn’t count toward the goal, according to CNCA.

Concrete as a CO2 Sink

Concrete has a quality that shouldn’t be overlooked when discussing decarbonization: It can serve as a carbon sink, CNCA said.

“Efforts to achieve net carbon neutrality in the cement industry should actively acknowledge and make allowances for the fact that a significant portion of emissions are naturally recaptured and sequestered over time,” CNCA said in its report.

According to the European Cement Association, concrete structures such as roads and buildings react with air and slowly absorb CO2. This process, known as recarbonation, takes place mainly at the concrete surface.

The association said there are ways to enhance the recarbonation of concrete. When a structure is demolished, piles of crushed concrete can be left exposed to the air for several months before being reused to maximize CO2 absorption.