Minnesota has passed the midway point on a 20-year journey in search of a green Xanadu: carbon-neutral buildings.

According to the Environmental Protection Agency, heating and cooling buildings is responsible for about 43% of all energy use in the U.S.

Adopted in 2009, the Minnesota Sustainable Building 2030 energy standard is an energy conservation program designed to reduce the energy use and carbon emissions of the state’s commercial, institutional and industrial buildings. It is a requirement for all state agencies and other entities that receive state bonding for new or renovation projects.

Based on the nationwide Architecture 2030 program but customized to fit Minnesota’s buildings, climate and policies, the standard requires increasing reductions in onsite energy-use intensity, as measured by British thermal units per square foot per year.

Projects built after 2010 were required to use 60% less energy than the average building with the same function and operation, using 2003 as the baseline. The threshold was increased to 70% in 2015 and 80% for 2020-2025, measured in both energy intensity and carbon intensity. It will be increased to 90% for 2025-2030.

After 2030, the requirement is a 100% improvement — net zero emissions.

SB 2030 is administered by the Center for Sustainable Building Research at the University of Minnesota. CSBR director Richard Graves said no other carbon emission reduction program compares to the magnitude and scope of SB 2030. Although it only applies to publicly funded buildings, Graves said it is “a good test bed” for practices others can use.

Customized Plans

Each project under SB 2030 is assigned a plan of cost-effective energy efficiency performance standards. At the heart of each plan is Building Benchmarks and Beyond (B3), a system for measuring buildings on metrics including potable water use, stormwater management and waste reduction in addition to energy consumption.

SB 2030 performance standards are updated at least every five years and must reflect reductions in carbon emissions resulting from utility decarbonization measures. They also must be cost-effective, based on a 12-year payback — down from 15 years earlier in the program.

B3 provides a framework of “tailored goals to specific projects,” Graves said.

Results

Almost 200 renovation and construction projects have been designed to comply with SB 2030, achieving 1,067,000 MMBtu in annual energy savings — equivalent to the building emissions of Stillwater, Minn., a city of about 18,000, Graves said.

More than 9,000 public buildings are tracking their operational energy use through B3 benchmarking, “which is a tremendous achievement,” he said.

During the fifth Best of B3 recognition event last month, Becky Alexander, a member of Graves’ B3 team, outlined recent research on 60 SB 2030 projects, which found that most achieved at least a 60% reduction in energy compared to the average 2003 building, with some hitting a 70% reduction.

A second analysis of 27 projects tracking their operational energy use found that 85% were operating at or below their SB 2030 standard, but about half of the projects are using more energy than predicted by their design model.

“That could be the result of unforeseen operational changes, inaccurate design assumptions and/or inefficient building operations,” she said. “So as it gets harder and harder to design to meet SB 2030, we anticipate additional challenges in operating to meet SB 2030. This really highlights the importance of strong coordination between the energy modeler, building designers and building operators during the design phases, as well as really strong follow-through during operations.”

“We are having 96% compliance for the projects that has to meet the 60% and 70% targets in 2010-2019,” Graves said. “We will see about the 80%.”

Role for Renewables

The increase to an 80% standard “means the energy efficiency strategies alone won’t be enough to achieve program compliance and that renewable energy” will often be needed, Alexander said.

The original program required generation be on site, said Graves. Current rules set up a hierarchy allowing siting elsewhere on the building’s campus, or within an owner’s portfolio for owners with multiple buildings. Renewable energy credits are a “last resort,” Alexander said.

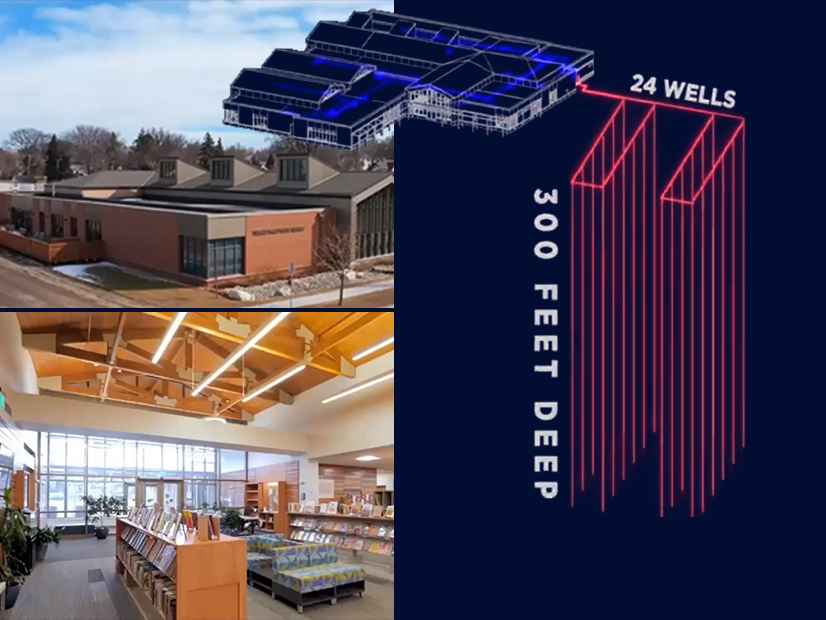

Because the cost of solar has decreased, Graves said, most future projects will require solar.

The first decade of SB 2030 has shown that when public sector developers follow the standard, it makes building operations and management more efficient and saves tax dollars, Graves said.

“This would work in other parts of the country as well,” he said. “It works here in Minnesota with the extreme elements, so it would be easier in other places.”