Nearly all miles traveled by Uber and Lyft drivers must be in zero-emission electric vehicles by 2030 under a new California regulation.

The California Air Resources Board (CARB) voted last week to adopt the regulation, called the Clean Miles Standard. It will take effect starting in 2023.

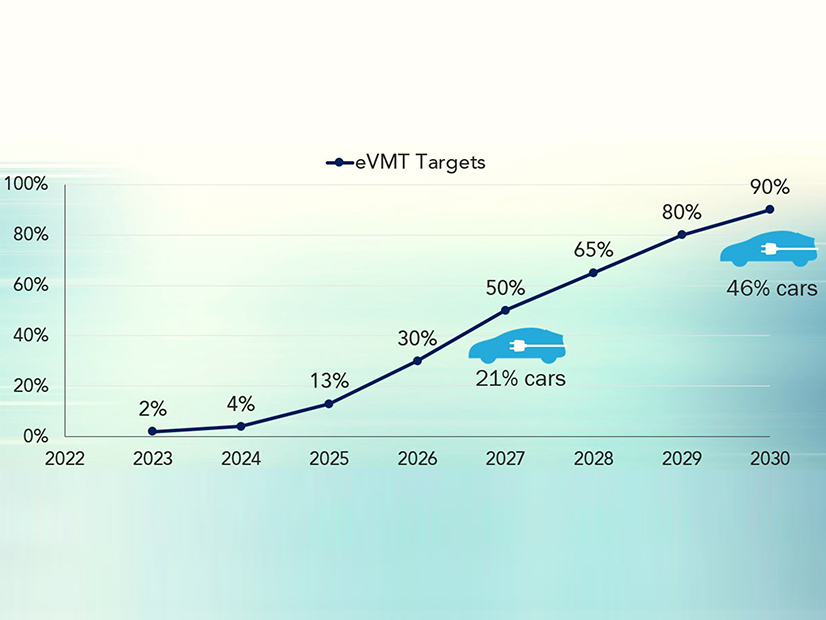

The regulation will require transportation network companies (TNCs) such as Uber and Lyft to reach 90% electric vehicle miles traveled (eVMT) by 2030. The eVMT requirements will start in 2023 at 2%, growing to 30% in 2026, 50% in 2027 and 80% in 2029.

The regulation also requires TNCs to get to zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, with interim CO2-reduction targets starting in 2023.

The TNCs will have a number of ways to reach the CO2 targets, including exceeding the 90% eVMT target; reducing “deadhead” miles, which are miles driven without a passenger; or increasing carpooling, in which there is more than one passenger per trip.

TNCs can earn credits to use toward the GHG targets when a passenger connects to transit through integrated trip-booking apps. Credits are also offered to TNCs that provide funding for sidewalk and bike lane infrastructure.

The Clean Miles Standard includes exemptions for TNCs with less than 5 million annual vehicle miles, as well as for wheelchair-accessible vehicles.

The standard heads next into rulemaking at the California Public Utilities Commission, which regulates transportation network companies.

A Growing Sector

The Clean Miles Standard is the result of Senate Bill 1014 by state Sen. Nancy Skinner (D), adopted in 2018.

The transportation sector accounts for almost half of greenhouse gas emissions in California, the bill noted, and light-duty vehicles contribute about 70% of emissions in the sector.

Vehicle miles from transportation network companies were 0.05% of the light-duty vehicle total in California in 2014, a figure that grew to 1.25% in 2018, according to a report from CARB staff.

“Although their VMT share may currently seem insignificant, this sector has potential for further growth,” the report said.

Uber has about two-thirds of the ride-hailing market share in California, and Lyft the remaining one-third, CARB said.

Uber last year announced a goal of having all rides take place in EVs in U.S. cities by 2030. Lyft announced a commitment to reach 100% electric vehicles on its ride-share platform by 2030.

Driver-impact Concerns

The requirement for 90% eVMT by 2030 doesn’t mean that 90% of TNC drivers must have electric cars by then. Because a small group of drivers account for most of the total VMT, only about 46% of vehicles used in ride-hailing services would need to be electric by 2030, according to estimates by CARB staff.

The EVs must be zero-emission, such as battery-electric vehicles or fuel-cell electric vehicles.

The calculation of eVMT only includes miles traveled while a passenger is in the ride-hailing vehicle. That way, TNCs can’t game the system by having EV drivers rack up extra miles with no passengers in the car, CARB staff said.

CARB’s approval of the Clean Miles Standard came despite many board members’ concerns about the impact on drivers. A CARB staff analysis found that TNC drivers could potentially save money by switching from gas-powered to EVs — especially if they’re able to take advantage of incentives — but those savings dwindle if the driver must pay for charging.

Board member Phil Serna said he was frustrated by the lack of data on TNC drivers, such as their income levels and the type of housing in which they live.

“Especially as it relates to people of color, that are perhaps lower income, that are living in multifamily units, the prospect of implementing this regulation is going to affect them so much differently than someone that is augmenting their principal source of income, who is not a person of color, who lives in a single-family detached home where they can enjoy Level 2, overnight charging,” Serna said.

Board member Davina Hurt also voiced concerns.

“I do think we need to create a standard, but I also think that this needs to be monitored closely,” Hurt said. “We need to commit to come back in a couple of years to see who this burden has fallen upon. And so that we can earnestly say that this is not disproportionately impacting the very people that we are trying to help.”