Dealing with climate change sometimes involves trade-offs.

What is good for the environment could have bad economic repercussions. Or a measure that could help fish might also harm wildlife along the shore.

Are there sweet spots in these balancing acts?

The Pacific Northwest National Laboratory in Richland, Wash., has come up with an approach to scientifically analyze these competing factors.

“It’s not hardware. It’s not software. It’s a concept,” Ann Miracle, group leader for PNNL’s Risk and Environmental Assessment Group, told NetZero Insider.

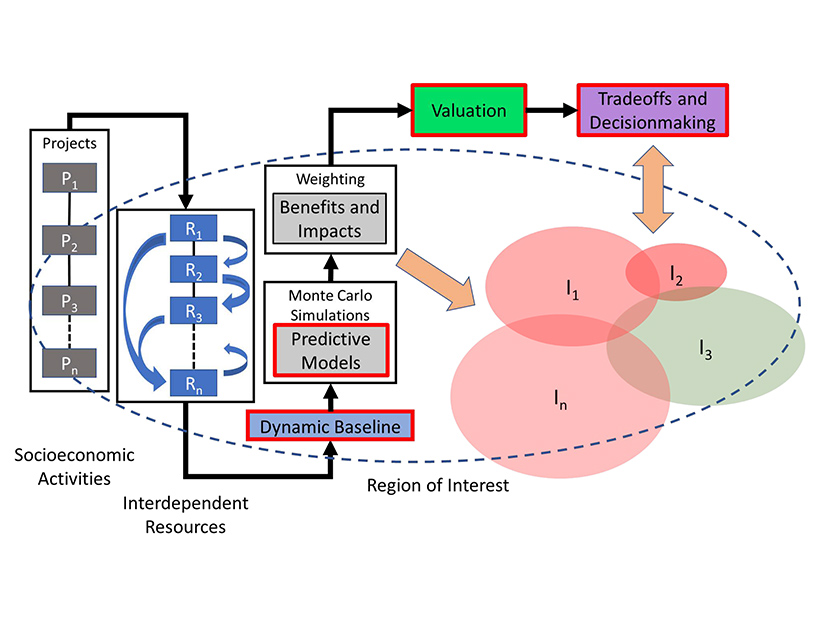

The PNNL concept is the Framework for Assessment of Complex Environmental Tradeoffs (FACET), which is designed to evaluate competing environmental, economic and social impacts.

A government agency would contract with PNNL to gather all the available historical environmental data and trends, then crunch that information with economic trends, plus costs of any mitigating measures. The process will likely include some original research, use existing or possibly new computer models, and potentially require writing new computer programs. Once the basic framework is set up, scientists can enter different environmental mitigation factors into the formulas and programs to predict the results of any scenario they can think of.

“The beauty of FACET is you can overlap climate change on top of it,” Miracle said.

A problem with this type of analysis is that “apples-and-oranges” comparisons are inevitable. The FACET approach tries to factor that wrinkle into its calculations, Miracle said.

The purpose of FACET’s approach is to look only at empirical and scientific data — leaving politics and decision making up to the government agencies that contract for such studies. “We’re not making the decisions. We’re providing the science,” she said.

Miracle said PNNL is in talks with several federal agencies to use a FACET approach. She did not have details available during the phone interview.

PNNL recently completed a pilot FACET project on the upper Colorado River basin, the region upstream of the Arizona-Utah border.

The pilot focused on scenarios involving cutthroat trout, looking at trade-offs related to river flows and withdrawal of water for cities, crop irrigation and power generation. The upper Colorado basin is facing one of the longest droughts in its history.

A typical scenario is if river flows are increased, river temperatures go down. That helps fish but translates to less water being stored for people.

“With climate change, river flows will likely decrease — there will be winners and losers,” PNNL earth scientist and hydrologist Rajiv Prasad, said in a press release. “Who gets the water and who’s willing to pay the most for it? … Our scenario’s projections showed that withdrawal could be restricted — sometimes as much as three to seven days per month in summer by the end of the century. Water would have to be obtained from elsewhere. This could have a disproportionate impact on those who can’t afford it.”