As the most litigious region on climate change issues, the U.S. may find existing and future cases in its courts influenced by global trends in cases that relate to value chains, human rights and subsidies.

“Since the signing of the Paris Agreement, we have seen over 1,000 climate change cases, and nearly 200 of those were filed between May 2020 and May 2021,” said Joana Setzer, assistant professorial research fellow at the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment (GRI). “Whereas the majority of cases (150 out of 200) continue being filed in the U.S., we also see how litigation continues to grow and expand across the world.”

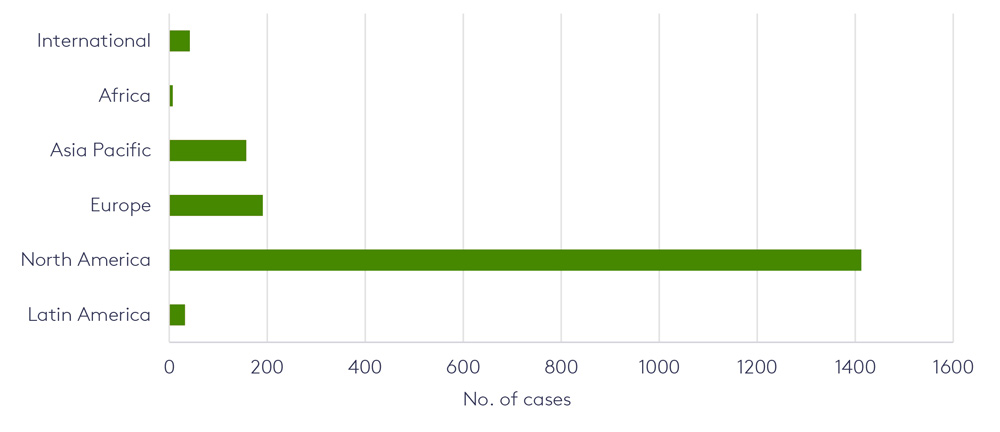

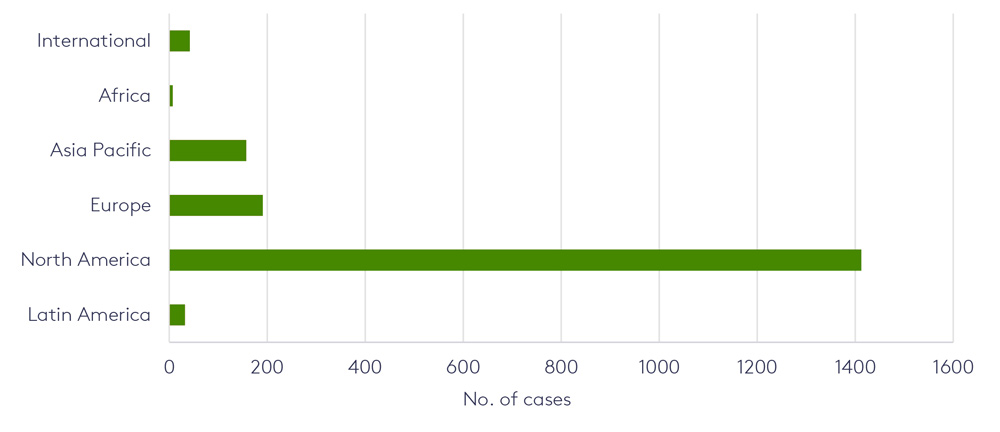

Setzer is co-author of a new GRI report on global trends in climate litigation, which said there have been 1,841 climate change cases identified globally between 1986 and May 2021. Of the total, three-quarters were filed before U.S. courts.

Strategic cases, or cases that try to bring about systemic change, are on the rise, Setzer said during a webinar on the report on Friday. They often are filed against corporations or governments, she said, adding that the recent landmark case, Milieudefensie et al. v. Royal Dutch Shell (Friends of the Earth v. Shell), is a stand-out example. In May, the Hague District Court found in favor of Friends of the Earth and ordered Shell to reduce its emissions by 45% relative to 2019 levels by 2030.

The win was significant on two fronts, according to the report.

First, the order to reduce emissions extended across Shell’s operations to those of its supply chain partners, pointing to a possible rise in cases related to value chains in the future. Because decarbonizing supply chains is viewed as a vital component to meeting climate goals, cases that force action on this front may come from a wide variety of sources.

One example, the report said, is a case that addresses deforestation to tackle both the release of carbon dioxide from the deforestation process and the protection of forests as carbon sinks. The case, which is unnamed in the report, claims that French supermarket chain Casino sourced beef from suppliers that practiced significant deforestation. It seeks to hold the company responsible for failing to conduct human rights and environmental due diligence in its supply chain, as required by French commercial code.

Second, the Shell case represents the first clear instance of a court using the Paris Agreement goal of limiting global temperature rise as a legal standard of conduct.

The Hauge court said that while the goals of the Paris Agreement are nonbinding, they represent a “universally endorsed and accepted standard” for preventing climate change. As such, the report said, the Shell case “may provide an important precedent for other ongoing actions where the Paris temperature goals and the need to reach net-zero emissions should inform legal obligations and standards.”

Duarte Agostinho and Others v. 33 States, a case filed last year before the European Court of Human Rights, is an example. Six Portuguese young people allege that the European Union member states and six other countries have not met their human rights obligations by not agreeing to emissions reductions that would limit global temperature rise.

The court fast-tracked the case in November.

Cases that are based on human rights, the report said, are another significant trend in global climate change litigation. Of the 112 documented human rights cases related to climate change, 29 were filed in 2020 and five in 2021.

“The majority of human rights cases have been brought against governments, and a small but significant minority brought against companies,” the report said. “In addition, human rights arguments have been used on at least one occasion by protesters seeking to defend their efforts to block new fossil fuel infrastructure.”

Early cases with a human rights focus put traditional rights in a new light.

The group of young plaintiffs in Juliana et al. v. United States, for example, sought the right to a stable climate under the U.S. Constitution. While that case was dismissed on appeal, a district judge ordered the parties to moved ahead to a settlement conference. And a similar case filed in October, Institute of Amazonia Studies v. Brazil, seeks to force the Brazilian government to meet emissions goals in line with a growing movement toward “climate constitutionalism,” the report said.

Additionally, human rights-focused climate litigation in some cases works to protect people from potential harms caused by climate policies or projects. The case Backcountry Against Dumps v. U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs, for example, claims that renewable energy generation facilities threatened human rights, health and safety.

Subsidies

A possible new subject of climate change litigation could rise from the growing consensus that governments must help curb fossil fuel production and exploration.

The International Energy Agency’s Net Zero by 2050 road map released in May called for a complete cessation of investment in fossil fuel supply projects. Meeting that expectation would require a “rapid policy shift from governments around the world, which provided an estimated US$320 billion in fossil fuel subsidies in 2019,” the report said.

There could be an increase in cases over the coming year that target government policies that incentivize fossil fuels and contradict net-zero targets.

“Such cases demonstrate the need for government actors to develop mechanisms to show that potential climate and human rights impacts are adequately and consistently factored into all decision-making processes if they are to avoid the risk of litigation,” the report said.

Other Trends Post Paris

Of the 200 climate change cases filed over the last year, 70% were against governments, which co-author Catherine Higham, policy analyst at GRI, says is consistent with the rate in all the cases filed since 1986.

There has been, however, an increase in the diversity of government entities involved in the cases.

“We still see cases filed against central government, but we’re also seeing cases against specific entities and particularly financial market entities that are government owned or government controlled,” she said during the webinar.

Nongovernmental organizations (NGO), individuals or individuals acting with NGOs make up most plaintiffs, but Higham said there is “a creative move in who is being included as litigants in cases.”

Examples include people with disabilities and political parties.

Cases filed since 2015 that focus on government commitments on climate are evolving, Higham said. “They challenge not just the level of ambition of governments, but what they’re doing to meet that ambition,” she said.

The Council of State in France, for example, ruled on Thursday that the country is not on track to meet its emissions goals for 2030. The court ordered the government to make changes in the next nine months to meet those goals.

There also is a trend in cases that challenge specific government actions that are inconsistent with climate targets, Higham said.

In the U.K., the Transport Action Network brought a case against the Secretary of State for Transport. It claims that a 2014 national policy on transport and infrastructure is not consistent with the country’s economy-wide net-zero target for 2050.

Another group of cases challenge government decisions to authorize third-party activity that might contribute to climate change, according to Higham. Those cases, for example, often focus on approvals for new carbon-intensive projects.

Wins and Losses

The report questions whether climate change litigation to date has been net positive.

A favorable case outcome would be a ruling that results in more effective climate regulation, the report said. An unfavorable outcome, on the other hand, would undermine climate regulation or increase GHG emissions.

But while a case might have an unfavorable outcome, rulings of law within a case in some instances may have important implications for new rights and obligations in future cases.

“Litigation is a double-edged sword, and it does come with a hefty price tag at times,” Michelle Jonker-Argueta, attorney for Greenpeace International, said during the webinar. “Some wins are landslides, and some are so technical, it will take more action to enforce and bring about the accountability of polluters and the vindication of rights of affected communities.”