Manufacturing and operating zero-emission electric buses, box trucks and tractor-trailers and their charging infrastructure has already generated billions in new economic activity and created hundreds of thousands of jobs, a supply chain analysis by the Environmental Defense Fund has found.

Based on a review of public records, supplier databases, other studies, SEC filings, investor notes and news articles the analysis found that since 2014 about 375 U.S. companies in 44 states have announced corporate investments of over $42 billion connected with zero-emission vehicles and infrastructure.

EDF’s study, released June 29, excluded manufacturers that make only electric cars but does include companies that historically have manufactured internal combustion engines that are now moving into electric drive systems.

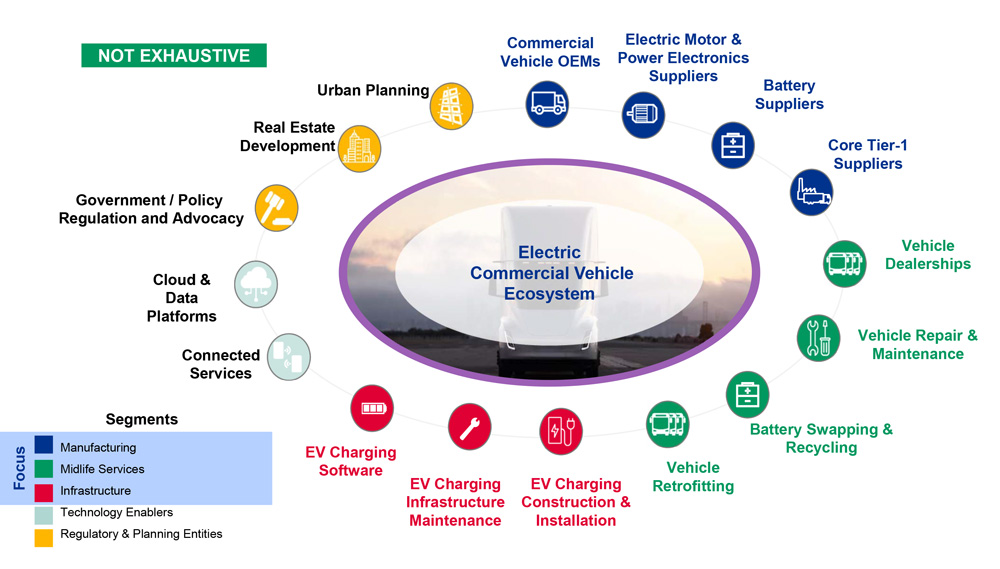

Calling the electric truck supply chain “a complex and rapidly evolving ecosystem,” the study found that:

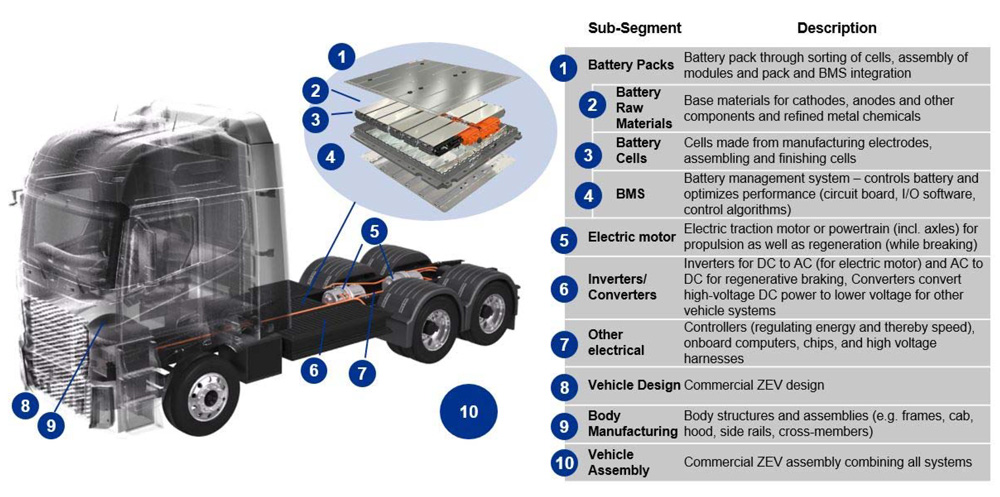

- Domestic manufacturing of vehicle components (e.g., body, motors, inverters, batteries) is by far the largest investment driver.

- Battery cell production is the largest investment at $12.1 billion, and battery pack production accounts for another $6.6 billion.

- Vehicle assembly investment is estimated at $6.9 billion.

Other segments in which investments are just beginning include:

- vehicle dealerships, repair and maintenance, battery swapping and recycling and vehicle retrofitting;

- companies involved in the construction and installation of charging stations, maintenance of the charging infrastructure and EV charging software development; and

- technology “enablers” such as cloud and data platforms.

The industry is also prompting action by regulatory and planning entities including state public utility commissions as well as real estate development and urban planning.

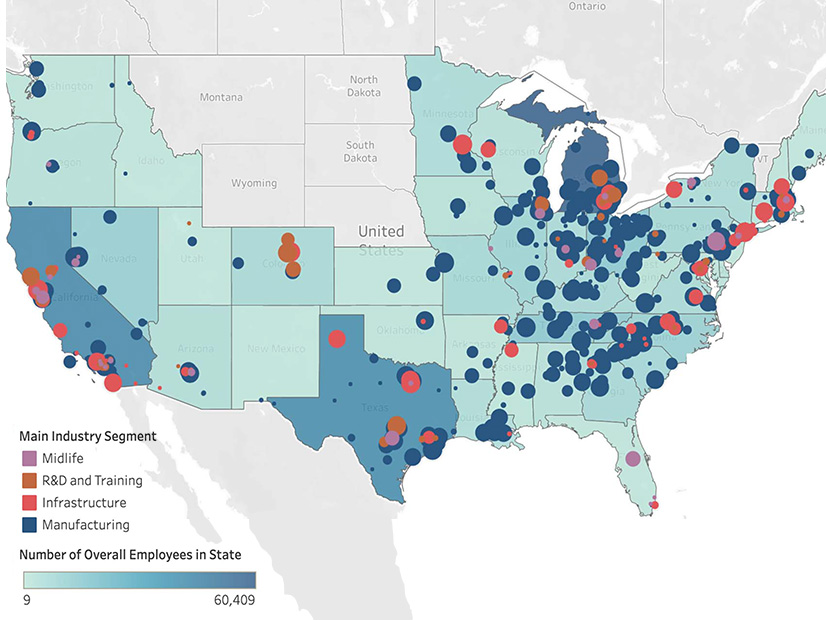

EDF found that 44 states host companies involved in the truck and bus EV supply chain at more than 1,000 locations. Most of the companies are involved in manufacturing of the vehicles or components rather than the charging infrastructure. And at least 22 states host companies with a greater than $100 million in announced corporate investments. On a state-by-state analysis, at least 20 states have 10 or more companies involved in the electric truck supply chain, the study determined. The top five states are California, Michigan, Texas, Illinois and Ohio.

Electric vehicle and vehicle component manufacturers employ 272,343 people, while companies working on infrastructure employ 42,545, the study determined. At least 35 states have 1,000 or more workers involved in the electric truck and bus supply chain.

In addition to the release of the study, EDF sponsored a June 30 electric trucking and charging infrastructure podcast produced by The Hill in which Pam MacDougall, EDF senior manager of grid modernization engineering and strategy, briefly interviewed a key staffer at a California-based trucking company that has been running two Volvo electric trucks in a pilot program since September 2020.

“We’re amazed at the reliability that we’re getting from the vehicles,” said Troy Musgrave, director of process improvement at Dependable Highway Express. “We really think that there is a place for electric heavy-duty vehicles in our industry.”

“What barriers do you still see you’re facing?” MacDougall asked.

“The first thing is the cost of vehicles. They’re extremely costly compared to the diesel trucks that we’ve used today. And, you know, we have to be transparent about the technology as it is today. [Electric] vehicles take longer to fuel.

“They can’t go as far on a single charge as a diesel tractor,” he said, a reference to the 18-wheeler tractor-trailer rigs known in the industry as “class 8” vehicles. “They can’t carry as much as a diesel tractor because of the weight of the batteries and the other components that go along with electric trucks.”

But he said the company was “surprised to see that 70% of the vehicle routes that we’re running in the box trucks, the smaller regional vehicles, can be met by the current technology and battery electric truck … that we’re using today.”

A challenge facing any company choosing EVs is the lack of a charging infrastructure, he added

“You can’t run the battery electric truck without the infrastructure to support it. Right now, I don’t see a good solution for public infrastructure in our kind of business,” he said. Instead, the box truck the company is testing can make its daily deliveries and return to the company depot without recharging on the road.

Asked what public policies are needed to help trucking electrify, Musgrave said a California incentive program to help trucking companies buy EVs is crucial because their cost is so high. “For carriers to take this [cost] on by themselves would put us at a competitive disadvantage,” he said.

EDF in March released the results of a broad study that argued the trucking industry would be unable to make the leap to electrification without state and federal incentives. (See EDF: Electrifying Heavy Trucking Could Save Money, Strengthen the Grid.)

The study was based, in part, on real experience of two other trucking companies operating electric trucks in California and concluded most of their runs could have been handled by electric trucks, at lower fuel costs than running diesel trucks. It also looked at adding distributed energy generation, wind or solar, to a public truck charging infrastructure, concluding that such a system could strengthen local transmission systems.