Announcing a bipartisan infrastructure deal — even with 11 Republicans on board — does not guarantee a fully fleshed-out bill with billions of dollars for new transmission, electric vehicles and resilience will reach President Biden’s desk.

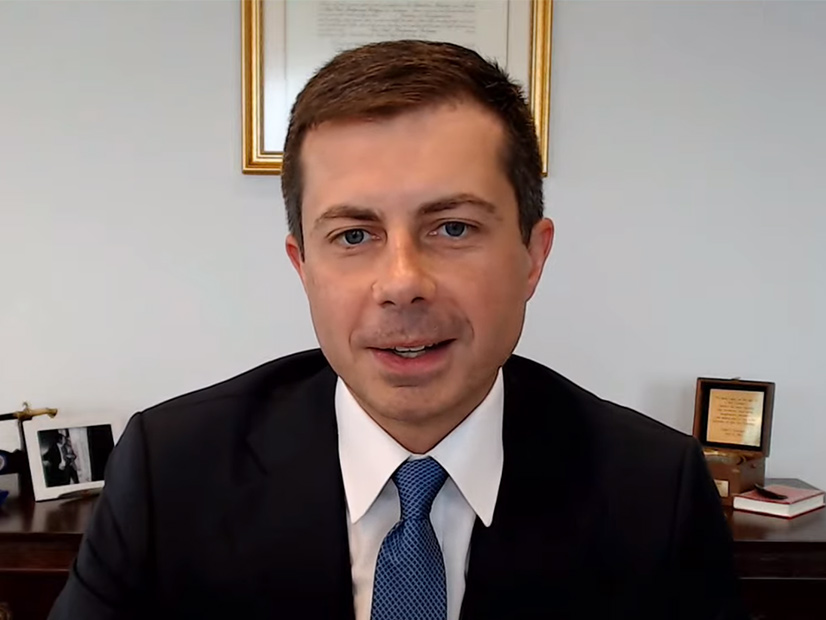

“You have things that are overwhelmingly popular on both sides of the aisle, across every ZIP code in America except Capitol Hill,” Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg said Thursday in an online conversation with Jason Grumet, president of the Bipartisan Policy Center. “I think the biggest threat is politics: some decision that it would be politically advantageous to fail. But by the same token, I can’t think of better politics than actually delivering something that the American people want.”

G

“Just think about the alternative,” Buttigieg said. “What it would be like for a Republican and Democrat to go back to their districts and explain why we couldn’t do something that the vast majority of Americans, business and labor, governors and mayors, all said we ought to do. That would be a very difficult thing to explain.”

The need to maintain momentum for the infrastructure package — and get it done — was the main message of the BPC webinar, which in addition to Buttigieg also featured a panel with labor and energy business leaders. The organization is one of many now solidly supporting the bipartisan package, but Grumet still had probing questions for Buttigieg.

“There’s always been some asymmetry between what the nation needs in terms of infrastructure and what local communities want next door,” Grumet said, talking about equity in infrastructure planning. “How do we integrate the desire to build in these communities in a way that actually embraces their economic development aspirations but doesn’t exacerbate environmental justice concerns?”

Buttigieg acknowledged low-income and disadvantaged communities have often been either neglected, disrupted or displaced by infrastructure projects. “That’s particularly been true in the history of how our highways came to be where they are: going often through black and brown neighborhoods, either because it’s the path of least resistance, which itself reflected political or economic dynamics of racial disparity, or worse, with a very direct intent to remove what was considered an undesirable neighborhood, [which] was often, in fact, a thriving and very important neighborhood for a minoritized group.”

Ensuring that infrastructure funds will benefit such communities will require planning and development processes that are “legitimately inclusive, and at the same time, flowing in a swift way … so that no one feels like they need to stand in the way of a project or an effort at the last minute,” Buttigieg said.

Solutions, however, will differ from one community to another, he said. “I don’t think the answers for the most part ought to come from Washington, but what’s clear is more of the money should,” he said.

Mobilizing Capital

Audience members also had sharp questions of their own about automobile fuel efficiency standards and whether or when the administration might consider a phase-out of gas-powered cars.

Regulated by the Department of Transportation, the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards are an essential part of transportation decarbonization, Buttigieg said. “No matter how good we get [with] EVs, there are going to be a lot of gas-powered cars on our roads for a long time … even when no gas cars are being sold, whenever that day might come, which is why having a high level of efficiency on the cars sold today, tomorrow, in 2026 and so forth is going to be so important,” he said.

At the same time, Buttigieg said, policy discussions on accelerating EV adoption should consider “the opportunity that electric vehicles represent in areas that maybe aren’t the first to leap to mind when you think about EV users — mainly rural [areas], where you’ve got people driving longer distances, which means almost by definition they’re going to save more money [with an EV]. It’s part of why we have got to make electric vehicles and electric pickup trucks affordable.”

With the bipartisan package providing only about half of Biden’s $2 trillion American Jobs Plan, another audience member asked about the role of public-private partnerships (P3) for infrastructure financing.

“What we know is there is a lot of capital, a lot of cash out there looking for a place to go,” Buttigieg said. “If we can mobilize that capital to solve public problems, if we can mobilize that capital to enhance the infrastructure capacities of our country, that’s a really appealing opportunity. What can’t work is for P3 to be used as an excuse to make an end run around important labor or environmental and other public policy goals, basically outsourcing the responsibility for doing the right thing.”

Power Cables Melting

Shuler was also bullish on the jobs that infrastructure projects would create, pointing to offshore wind development as “a top-drawer example of how labor and management can work together to create a high-road, high-wage strategy for the entire sector, so that this promise that we hold out there of a clean energy future is actually growing good jobs, and it’s benefiting everyone.”

“To scale up offshore wind, the big need right now is to leverage the huge pipeline of projects that are on the horizon and translate that into the production of the major components in the United States,” Shuler said. “We are way beyond the volume needed to support turbine and blade factories. If we can produce the major [turbine] components here in the United States, the bill of materials is stupendous. It’s literally hundreds of tons of steel and copper and specialty metals.”

Electric utilities are part of the “decarbonization narrative,” Blue said, pointing to Dominion’s Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind project, with 2.6 GW of turbines to be located 27 miles off Virginia Beach. Completion is slated for 2026, he said. The utility is currently building an all-American-made installation vessel.

At the same time, Blue said, getting to net-zero emissions by 2050 will mean “continuing operating our nuclear facilities, which are the only baseload, non-emitting sources of electric generation that exist today.”

Rice argued for natural gas as a cleaner alternative than the coal that still provides about 20% of U.S. power and as support for accelerated renewable energy deployment. “The more natural gas we use creates more opportunities for renewables and is going to be key for lowering emissions,” he said.

Rice also sees the growing hydrogen economy as creating a virtuous cycle for natural gas. “Hydrocarbons can be transformed into a decarbonized form of energy,” he said. “We’re talking about using natural gas as a feedstock to produce hydrogen and pairing that up with our wellbores that are depleted. Those can serve as carbon sinks, so not only do we have a low-cost form of natural gas that could be a feedstock for hydrogen, we also have a home to store the carbon.”