A Nova Scotia company with a novel electric thermal storage (ETS) product recently won $25,000 and earned a pilot project in Vermont through the DeltaClimeVT Energy 2021 business accelerator.

Neothermal Energy Storage took the first-place prize based on rankings by members of the accelerator cohort over a three-month program.

“It felt amazing, and we were genuinely shocked because the other companies in the program are really high caliber,” Neothermal co-founder Jill Johnson told NetZero Insider.

The goal of the program, according to DeltaClimeVT, was to reduce energy use and greenhouse gas emissions in residential and small commercial and industrial buildings, while increasing adoption of distributed energy resources (DER). Two other cohort members also earned pilot projects in Vermont. (See Vt. Climate Tech Accelerator Drives 2 New Utility Pilots.)

The DeltaClimeVT experience, Johnson said, was much different from other accelerators in which the company has participated.

“This was probably the best accelerator that we’ve done because it had much more concentration on hardware, technology and climate technology companies,” Johnson said.

Vermont Sustainable Jobs Fund administers the accelerator program with support from a group of Vermont utilities to help bring clean tech innovation to the state.

The ability to speak with utility representatives was a significant benefit of the program, Neothermal CEO and co-founder Louis Desgrosseilliers, told NetZero Insider.

“Part of the program guaranteed that we would sit down with people either in the C-suite level or director level within these organizations that we want to connect with,” he said.

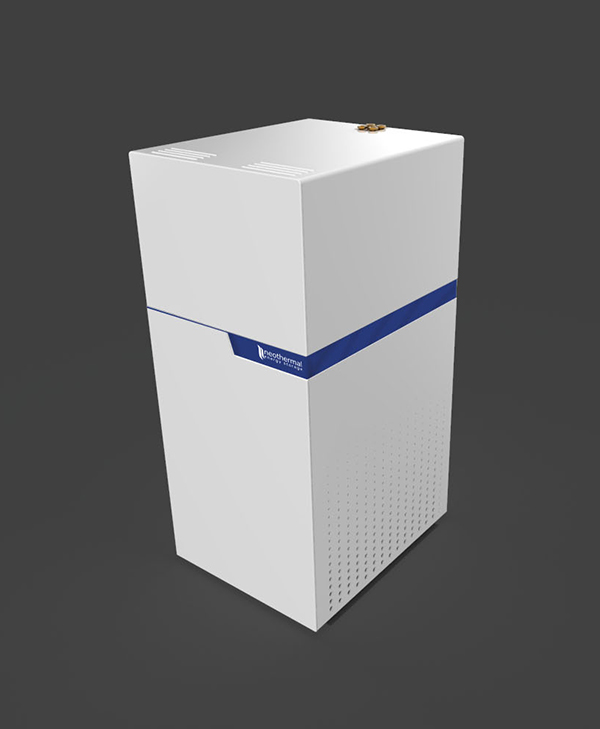

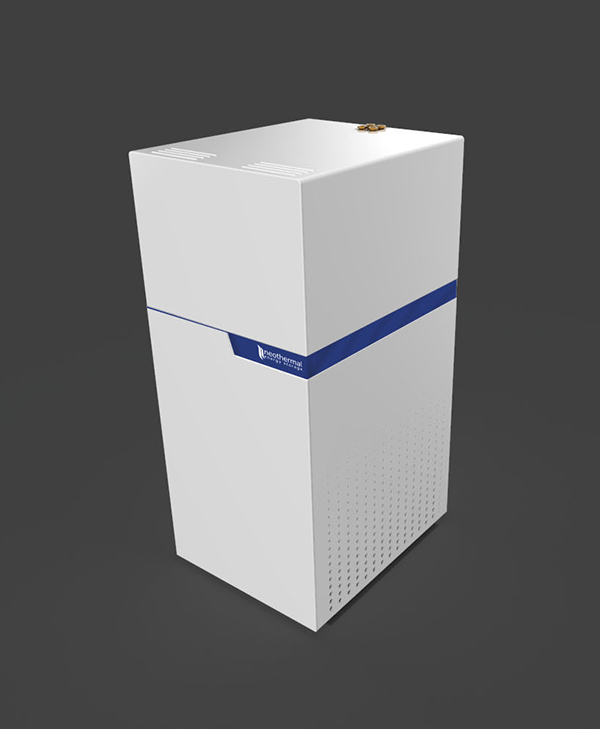

Neothermal’s ETS system came from Desgrosseilliers’ doctoral work at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia. The system uses sodium acetate trihydrate to store heat from off-peak electricity, offering a pathway for buildings to transition to electric heat from oil-fired boilers and furnaces.

“Where other thermal storage that’s used today is either to heat up water or to heat up bricks, both of those methods are simply making things hot,” Desgrosseilliers told NetZero Insider. “Our system uses a combination of that and a chemical change that allows us to do things with more energy storage density and at lower temperatures than will be required with other materials.”

A typical home would require four ETS units, which are installed adjacent to, and integrate with, an existing boiler or furnace and reduce fuel consumption by up to 90%, according to Johnson. An add-on option also allows the ETS to supply heat to an electric hot water system. At full capacity, the ETS would provide between six and 12 hours of heat to a home.

Neothermal also is laying the foundation for DER aggregation so groups of web-enabled ETS systems in the future could respond to signals from the grid.

The systems, for example, could take up excess renewable energy on demand that might otherwise be curtailed, Desgrosseilliers said.

Pilot Project

The municipal electric utility in Burlington, Vt., awarded Neothermal a pilot project that Johnson says works with the city’s goal to have net-zero emissions by 2030.

Neothermal pitched a pilot simulation of the ETS system to help the utility address its goals around building electrification, she said. The company will then move to a physical pilot in 2022 or 2023 with the assistance of Vermont’s only natural gas distribution company.

“Vermont Gas showed a lot of enthusiasm for our technology early on in the program,” Johnson said. “We’re going to be working with Burlington Electric as well as Vermont Gas on not only off-peak electricity, but having renewable natural gas provide the backup power to the system.”

When the ETS system is depleted, she said, the home would use renewable natural gas to “top up” any heat that is needed.

The companies are still working out the details for how to proceed with the pilot.