Eight low-and moderate-income households in Virginia could cut their greenhouse gas emissions by about 25% and each save hundreds of dollars as the result of a pilot project that provided home energy efficiency upgrades and swapped out natural gas heating and cooking appliances for electric ones.

The Community Climate Collaborative (C3) and the Local Energy Alliance Program (LEAP), both based in Charlottesville, Va., partnered on the project to weatherize and electrify the LMI homes, located in the city itself and surrounding Albemarle County. The pilot ran from 2019-2020, according to a recent webinar on the project.

“We were looking for [a way] to combine a climate solution with affordable energy,” said Caetano de Campos Lopes, director of climate policy at C3.

The project worked with local HVAC service providers who switched the eight homes from natural gas, kerosene and fuel oil to all-electric heating and water heaters, even replacing an old gas-powered clothes dryer with a new electric model. The local providers or LEAP worked on the stove replacements.

The main criterion for participation, according to Susan Kruse, C3’s executive director, was a qualifying LMI income—under $74,797, which is 80% of the state median income, based on figures from the Virginia Housing Development Authority. All the homes had weatherization and other energy efficiency measures completed either at the same time or up to a year before the electrification, Kruse said.

“An anonymous private foundation funded the electrification of the homes, but we also used state energy efficiency programming funds,” she told NetZero Insider in an interview. “LEAP was in charge and managed a team of private contractors. We were the main point of contact for the families, did data collection and will do advocacy” for state and local policies that will support similar projects, she said.

While small, the project hits on some big issues.

Virginia is targeting a 10% reduction in retail electricity consumption over 2006 levels by 2022, and the Grid Transformation and Security Act, passed in 2018, requires the state’s electric utilities to invest $1 billion in energy efficiency projects over a 10-year period.

The impact of these policies for LMI households could be significant. Low-income families pay more of their disposable income on energy, in some instances as much as three times more, than higher-income households, according to information from the U.S. Department of Energy. The national average for energy expenditures is around 3% of disposable income, according to a study from the American Council for an Energy Efficient Economy, while the DOE figures show low-income Virginians spend 6 to 8%.

“Higher income homes may have a larger footprint, but also tend to be more energy efficient,” Kruse said.

Uneven Results

At the same time, buildings and the construction sector accounted for 36% of final energy use and 39% of energy and process-related carbon dioxide emissions in 2018, according to global figures from the International Energy Agency. The EPA found residential and commercial buildings accounted for 13% of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions in 2019.

C3 estimates the eight homes could cut year-round GHG emissions by 25.7%, or 40,551 pounds. Two of the homes, which had been using heating oil, saw emissions reductions of 56.3% and 68.0% in the first quarter of 2021, while emissions reductions for homes that formerly used natural gas followed a less clear trend, with some actually showing small increases.

However, de Campos Lopes estimated that overall, the homes’ total GHG emissions over the next 20 years could decrease by as much as 2 million pounds.

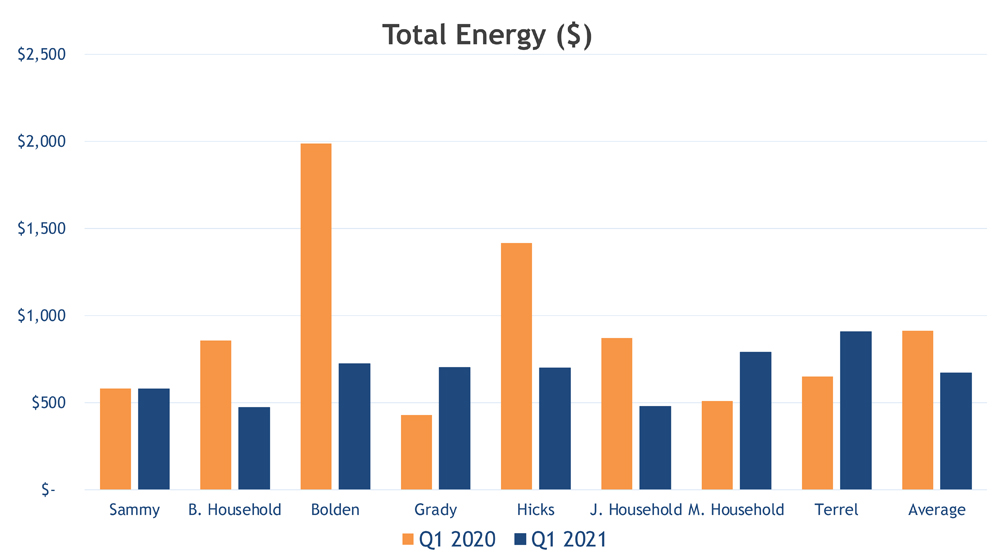

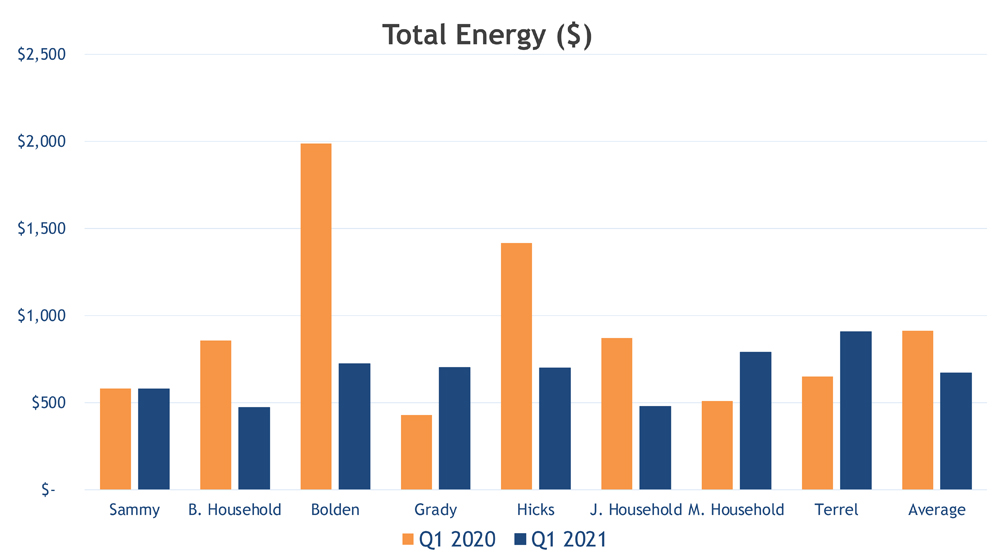

Similarly, as with emissions, the impact of the upgrades and electrification on household energy costs were uneven, with some seeing major savings and others seeing modest increases. C3 said that the individual patterns of energy use and other factors in each home will need to be evaluated.

However, overall, the net present value of projected savings adds up to about $32,000 over the next 20 years, averaging $4,000 per household, de Campos Lopes said.

The uneven results for the homes switched from natural gas come at a time when home electrification has become a highly divisive issue in some states. More than 40 local jurisdictions in California have banned natural gas hookups in new construction, while 19 states have passed legislation, backed by the gas industry, barring municipalities from prohibiting or limiting access to natural gas or propane. For example, Florida bars its political subdivisions from taking “any action that restricts or prohibits … the types or fuel sources of energy production which may be used, delivered, converted, or supplied” by electrical utilities or suppliers of natural gas or petroleum gas.

On the other hand, larger environmental organizations have taken up the cause of clean energy, such as the Sierra Club with its “Ready for 100” campaign, which is advocating for communities across the country to adopt 100% clean energy goals.

Virginia has yet to see any action on natural gas hookups — for or against — at the state or local level. But, the Consumer Energy Alliance, an advocacy group representing a range of business and energy organizations, released a report in August claiming a natural gas ban in the state, requiring existing homes to be retrofitted, could cost individual households thousands of dollars.

C3 has noted that under Virginia’s Clean Economy Act of 2020, 41% of the state’s power will come from clean energy by 2030, with the state targeting 100% clean energy by 2050. C3 estimates that this ongoing transition to clean power could cut carbon emissions from the eight homes by 95% by 2040.

Kruse said that one of the key lessons learned from the project is that program flexibility is essential when upgrading low-income homes to electric. “It is critical to pair electrification with air sealing, insulation and other energy efficiency measures to maximize cost savings,” she said.

The savings for individual homes can vary widely, she said, but local and state policy can help ensure that electrification works for everyone.

Looking ahead, Kruse said that now that the initial work on the eight homes is done, C3 intends to “keep up with these families as much as they have the appetite for, so they continue to save money, and we can help them when necessary. We will also continue to advocate for local and state policy changes.

“More projects like this need to happen,” she said, but one problem is that Virginia’s state-sponsored energy efficiency programs don’t allow fuel switching work to be done with state funds. While in this project, private foundation money covered the gap, “that thinking needs to evolve,” she said.