New Jersey’s local governments and residents are taking the initiative to fight climate change and promote renewable energy, with Jersey City creating its own climate change master plan and voters in three communities prodding their elected officials to opt to provide clean energy to residents.

Jersey City, the state’s second largest municipality, approved its own 103-page master plan in June that echoes the state Energy Master Plan, calling for greater use of electric vehicles and measures that will improve the efficient use of energy in buildings. The city is also one of 18 communities that have secured state grants totaling more than $22 million to acquire zero-emission school buses, garbage trucks or shuttles. The Bergen County Prosecutor’s Office, in the state’s most populous county, recently acquired a Tesla vehicle that will be fitted out to show area departments how EVs can ably serve the needs of law enforcement, the office said.

“Our hope at the county level is to embrace positive advancements in ‘green’ technology and exceed the goal of the state,” said Elizabeth R. Rebein, assistant prosecutor/spokeswoman for the office. “We expect to see a reduction in repair and maintenance costs as compared to conventional vehicles, and the elimination of fuel costs.”

Elsewhere, voters — led by Food & Water Watch, a nonprofit environmental advocacy group — are driving the shift to clean energy. The town councils in three communities — Woodbridge, North Brunswick and Long Branch — each approved ordinances in August that require their governing bodies to set up a program giving residents the option to use an electricity provider that is heavily sourced with clean energy.

Food & Water Watch triggered the ordinances through a combination of the state initiative-and-referendum law and a law that allows municipalities to purchase electricity through community choice aggregation (CCA). In each of the three municipalities, residents collected enough signatures to trigger the enactment of an ordinance requiring the governing body to strike a deal with an electricity provider that would enable residents to buy electricity of which 50% or more is from clean resources.

With those three ordinances in place, 11 New Jersey municipalities have enacted CCA programs and a 12th is heading that way, said Charlie Kratovil, canvas director for Food & Water Watch in New Jersey.

“The goal is ultimately to win the big changes we need at the federal level to get us to 100% renewables ASAP,” he said. “So, this is one way for both regular citizens and also local officials to weigh in on that and demonstrate that it can be done and that we need to do it.”

Not all the organization’s signature drives have been so smooth. In Teaneck, the township rejected signatures that were collected electronically online because of the COVID-19 pandemic. But on Monday, a New Jersey Superior Court judge ruled that the signatures were valid and required the issue to go before voters, Food & Water Watch said.

Woodbridge Mayor John E. McCormac, whose municipality has forged a statewide reputation for its environmentally friendly programs, said his green initiatives aren’t driven by a broad view of climate change but from the dual goals of supporting sustainability while taking a cost-effective strategy for his residents.

“Both greens work,” he said. “It’s green for the environment; it is green for the budget. Because it will save money and will protect the environment at the same time. All those things are things we very much are aggressive with.”

The townships’ green initiatives include numerous solar installations atop of municipal buildings, a thriving bicycle-sharing program, the installation of low-energy lights around the township, and the successful application for state funds to purchase three-electric garbage trucks and two electric shuttle buses. (See NJ RGGI Spending Focuses on Transportation.)

The township four years ago enacted an energy aggregation program, but it didn’t work out and was canceled, said McCormac, who declined to say why because he did not want to affect the upcoming bid process for an electricity supplier. Now that the issue has been forced on the municipality by the voter drive, “we’re going to look at it again,” he said. “And hopefully, this time around, it will be better.”

Focusing on Local Needs

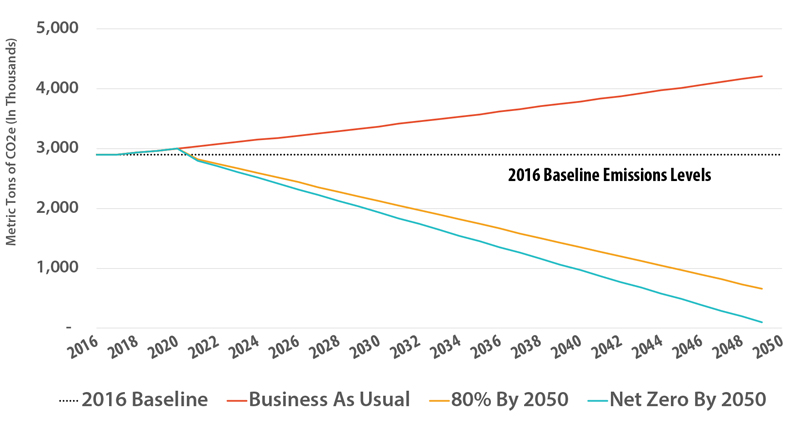

The ground-level initiatives are unfolding amid Gov. Phil Murphy’s drive to reach the goals of his master plan, released in January 2020, which calls on the state to use 100% clean energy by 2050. It also calls for a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions in the state by 80% below 2006 levels.

The plan outlines seven strategies for reaching the goals, including accelerating deployment of renewable energy, and reducing energy consumption and emissions from the transportation and building sectors.

The city, which sits on the Hudson River across from New York City, suffered extensive flooding at the start of this month, when the remnants of Hurricane Ida dumped between 5 and 8 inches on the region, with streets and basements flooded, and more than 100 vehicles abandoned in the water, according to local news reports. Last week, the federal government added Hudson County, in which Jersey City is located, to the list of New Jersey counties designated as major disaster areas.

Jersey City’s master plan, called the Climate and Energy Action Plan, “follows the state’s overall goals but looks specifically at how we can tackle those goals at a local level as efficiently and effectively as possible and in a way that meets the needs of Jersey City residents,” Wallace-Scalcione said.

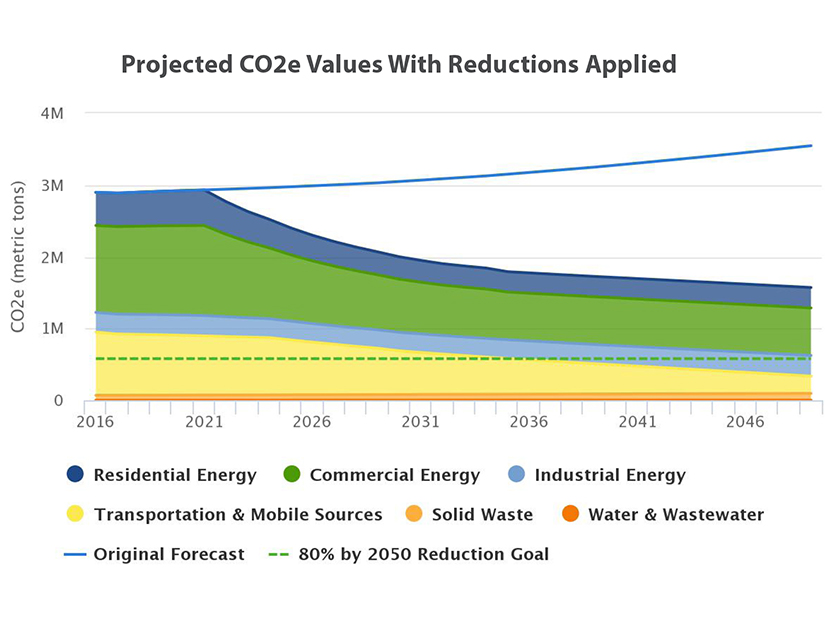

The plan, which requires the city to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to 80% below 2015 levels by 2050, reports that 67% of the city’s greenhouse gas emissions come from buildings and 30% come from transportation. Another 3% come from waste.

Jersey City’s master plan proposals include a goal of ensuring that 100% of all new municipal vehicles are electric by 2030 and recommending that the city partner with NJ Transit, the state’s mass transit agency, to create a plan to make its fleet 100% electric by 2035.

The plan also proposes that all new buildings over 25,000 square feet should be solar and EV ready by 2022, and all buildings of that size should benchmarked for energy use by 2023. The plan also calls for the city to “streamline and clarify the permitting process for building-mounted solar panel systems” and establish a local community solar program.

Overall, the city should be using 100% clean energy by 2030, the report says.

Collective Clean Energy Purchasing

That same goal is enshrined in the ordinances passed in Woodbridge, North Brunswick and Long Branch. The ordinances require each municipality to solicit request for proposals for “electric generation service and energy aggregation services on behalf of the township’s residents and businesses,” and to set up a CCA program.

The program, which must be implemented within a year of passage of the ordinance, must result in a contract that gives customers the option “to opt up to 100% renewable electricity” and stipulates a minimum, and rising, percentage of renewable energy provided under the program. That starts at 50% in the first year, rising in increments of 10% each year to reach 100% renewable energy in 2030.

Under the state’s initiative-and-referendum process, residents can force an issue toward enactment via a petition with signatures from 10% of the number of votes from the last General Assembly election. Food & Water Watch typically picks communities with a strong base of support from its 60,000 members statewide, Kratovil said.

If enough signatures are collected and certified, the municipal government must either adopt an ordinance reflecting the wording of the petition or can decline, and the issue is automatically placed on a ballot for voters to decide, he said. In most cases, the municipal governing body opts to pass an ordinance enacting the program, but in the case of Piscataway and East Brunswick, the governing bodies declined to do so and the issue went to the ballot, he said.

“In the towns where it’s been put on the ballot, the voters have been overwhelmingly supportive,” he said.