More granular data and improved computing power are allowing economists to refine their climate change predictions — and, they hope, influence policy.

“It’s incredibly exciting,” University of Chicago economist Michael Greenstone said Monday during a Climate Week NYC panel discussion hosted by the New York University School of Law’s Institute for Policy Integrity. “We’re at the dawn of what I think is a new era.”

Until recently, research on climate damages was “too idiosyncratic,” said Greenstone, the director of the Energy Policy Institute at Chicago. Integrated assessment models lacked transparency, and few studies were replicated to confirm initial findings, he said.

The new tools should eliminate “blind spots” on subjects such as climate-driven migration.

‘Politically Acceptable and Cost Effective’

Maureen Cropper, professor of economics at the University of Maryland at College Park, said better data can help with the challenge of designing policies that are both “politically acceptable and cost effective.”

“There’s been a huge, a huge literature evaluating the Clean Air Act after the fact to look at its cost effectiveness. And I think this needs to be done to find the policies and their opportunities [to address climate change]. And I also think there are opportunities to understand the impacts of overlapping climate policies,” said Cropper, a senior fellow at Resources for the Future and the former chair of the EPA Science Advisory Board’s Environmental Economics Advisory Committee. “This is an important research agenda.”

Previous data and computing limitations prevented scientists from determining how climate change would affect different parts of the globe differently, Greenstone said. “The most disaggregated [data] was to divide the world into 16 regions. That has the unfortunate flavor of saying that climate change is going to be the same in Miami as it is in Minneapolis … and that, I think, led to statements like, ‘Global GDP will decline by 4% by the end of the century, on average.’ The problem is nobody lives at the global average,” he said.

Hot days don’t kill people in Houston because the region has adapted with air conditioning, he noted. But heat waves in the Pacific Northwest this summer killed more than 100 people and sent thousands to emergency rooms because those areas are not prepared.

Providing more granular information “allows communities to know what they should do to adapt. What you should do in Miami is very different than probably what you should do in Seattle, Wash.,” he said. “And then the kind of X factor — which I can’t prove, but I think is true — is by communicating to people what climate change will be where they live, my view is that that might unlock some of the political resistance about doing something about climate change.”

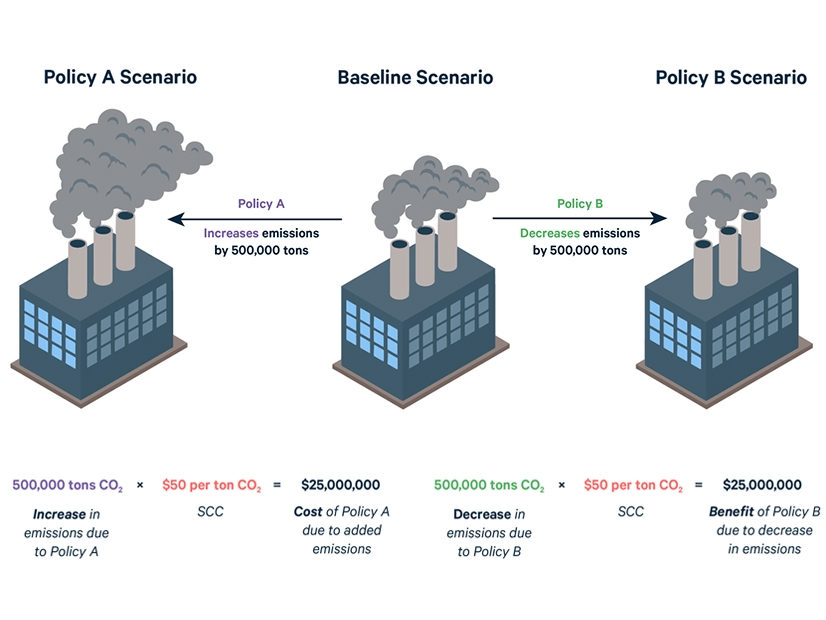

Social Cost of Carbon

One product of the improvements should be the Biden administration’s revision to the social cost of carbon (SCC).

Cropper expects the number to be much higher than the interim price set in February at $51/ton, saying the calculations underlying the price ignored research done since 2010. “If you look at the integrated assessment, models that are underlying the current estimates and [the] climate science part of those models, you have the peak impact of emitting a ton of CO2 on mean global temperature occurring in about 60 years. And recent climate science suggests this is going to occur is something like 20 years from now.”

Lowering the discount rate to 2% from the current 3%, as some have recommended, would increase the price from $51 to $125, she said.

Greenstone was co-leader of the Interagency Working Group on the Social Cost of Greenhouse Gases during the Obama administration, an experience he called “the most gratifying … and the hardest thing I’ve ever done professionally.”

“A ton has changed since 2009,” the year President Barack Obama took office. “And we’ve got a way better understanding of climate projection,” said Greenstone, who also expects a higher price.

“In 2009, and 2010 I think, there was a judgment that it was too challenging administratively to account for uncertainty. And so effectively, the uncertainty was valued at zero. And yet, we know … people buy insurance to protect your house against fires; car insurance; all kinds of insurance. We know that people just like us are willing to pay to get rid of [uncertainty]. … That should be an adder that goes on top of” the carbon price.

“I hadn’t appreciated this as an academic, but the different [federal] agencies are there to fulfill the mission of their agency; they’re not necessarily there to fulfill the broad societal goal. And so you had some agencies that effectively thought that the social cost of carbon should be infinite. And you had some who effectively thought that it should be zero,” he said. “So finding common ground, that was a big challenge.”

Greenstone recalled “a very, very nasty fight about the equilibrium climate sensitivity parameter distribution, which basically says how much warming you’ll get for a doubling of CO2.”

“We had made a decision about that. And then a very important person in the government tried to relitigate that,” he said. “Everyone was dug in … and finally, the only way we were able to resolve it — this was in the midst of the Great Recession, and the economy was losing several hundred thousand jobs a month — was to say, ‘OK, would you like to ask the president [for] an Oval Office meeting about the equilibrium climate sensitivity parameter distribution?’ And there was total silence. And then we were able to move forward.”

Al McGartland, chief economist for EPA and director of the National Center for Environmental Economics, said the new SCC could have an impact on FERC’s decision-making. “The great power of the social cost of greenhouse gases or carbon is it provides a way to create a level playing field for decisions,” he said. “In building out transmission, we’re only thinking about the economic benefits in terms of electricity rates, and not accounting for the benefits that could be provided by bringing low-carbon energy sources to more parts of the country. And were the social cost of carbon to be used in that decision-making process, I expect there would be greater construction of transmission lines than we currently see.”

NYU’s Richard Revesz, director of the Institute for Policy Integrity, who moderated the session, said he would like to see RTOs petition FERC to include a carbon adder in their generation dispatch algorithms. “That would be essentially the equivalent of a carbon tax on the wholesale electricity market … which would be a very attractive policy,” he said.

A ‘Rock in the Shoe’

Greenstone said it is essential that researchers publicize their findings beyond academic journals to become “like a rock in the shoe of policymaking [that] just can’t be ignored.”

He also said the U.S. should mandate that companies disclose their carbon footprints with the kind of rigor and standardization used in the financial reporting of publicly traded companies.

“That proved to be really important in giving people confidence in financial markets and allowing for financial markets to operate more efficiently,” he said. “I see a lot of desire by public companies and organizations who would like to begin to voluntarily do something about their carbon footprint, and the [absence of] credible numbers on what everyone’s emissions are … a self-inflicted wound.

Mandatory reporting on greenhouse gases “would help build the foundation of markets for people to voluntarily reduce their emissions, which are currently very, very immature and lead to ineffective solutions.”