Physicians, researchers and neighbors of a natural gas compressor station in Weymouth, Mass., are skeptical of an environmental assessment that found no public threat from oil, asbestos or arsenic contamination on the site, which formerly housed an oil tank and coal generating station.

Enbridge’s (NYSE:ENB) Algonquin Gas Transmission is accepting comments until Sept. 29 on the Phase II Comprehensive Site Assessment (CSA) conducted by consulting firm TRC Environmental Corp.

At a virtual public hearing Sept. 15, TRC explained the environmental sampling it conducted in response to the discovery of oil in subsurface areas near where an 11.2-million gallon fuel oil tank once stood on the site in the Fore River Basin, an industrial site for decades that is next to two state-designated environmental justice communities.

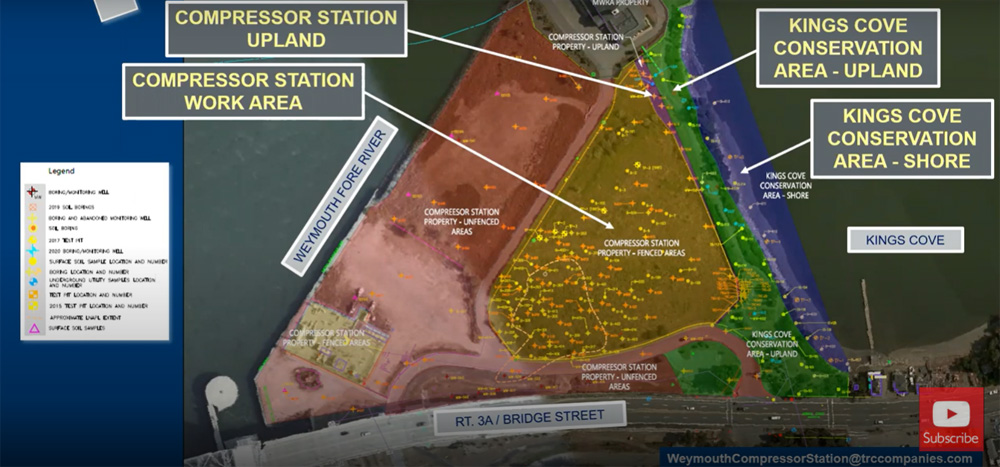

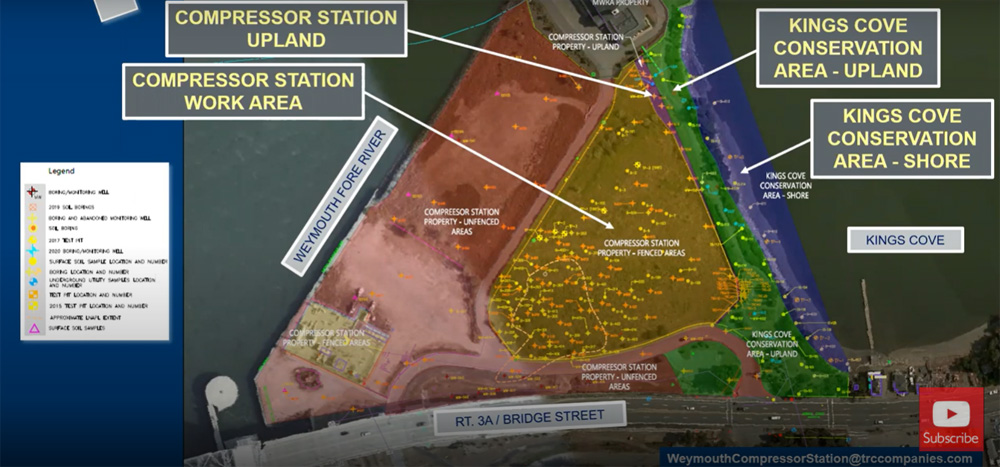

TRC said it conducted 140 soil borings, dug five test pits, installed 31 groundwater monitoring wells and collected more than 300 soil and 110 groundwater samples at the site of the Weymouth compressor station, which is built on man-made fill that includes bricks, dredged material, coal ash and “clinkers” — noncombustible residue from coal-fired generation. The site is adjacent to a public park, the Kings Cove Conservation Area, and Calpine’s Fore River Energy Center, a 731-MW natural gas combined-cycle generator.

‘No Significant Risk’

TRC Project Manager Matthew Oliveira said the sampling found the underground oil was not moving or a threat to groundwater and that no asbestos had been found in any of nine kinds of bricks sampled.

“[For] anyone visiting the site, there is no significant risk,” Oliveira said.

But many of the more than 40 people who attended the hearing expressed skepticism of the findings.

Phil Landrigan, director of the Program for Global Public Health and the Common Good at Boston College, said in an interview with NetZero Insider that asbestos-containing bricks used in the former coal plant are strewn around the peninsula where the compressor station is located.

The state’s health impact assessment shows that residents in Weymouth have higher rates of cancer, pediatric asthma and cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. Concern that the compressor could exacerbate health threats have been heightened because the plant has experienced four emergency releases of gas since it went into operation in fall 2020. The most recent release was in May. In February, FERC responded to the earlier releases by issuing an order seeking input on whether it should reverse its approval of the compressor station. FERC’s order is being challenged by the station operator in appellate court. (See Algonquin Gas Appeals FERC Order on Weymouth Compressor.)

Landrigan told NetZero Insider that TRC’s evaluation was flawed because it failed to consider the risk of fire and explosion that could cause widespread distribution of all the carcinogens in the fill dirt and incinerate houses in the area. “No question, fire and explosion is the biggest potential hazard associated with this facility,” he said.

Schools and homes for the elderly also sit close enough to the facility that if there was an explosion, they would be incinerated, according to research by the Greater Boston Physicians for Social Responsibility. One of the schools caters to children with special needs and limited mobility, making an evacuation difficult.

“I think one of the reasons that industries, including this compressor station, have been sited there is because it is a low-income, blue collar, 46% minority community with limited political power,” Landrigan said. “I just think it’s morally and ethically wrong.”

Since Enbridge paid TRC for the site assessment, the findings must be “very carefully assessed and possibly discounted,” Landrigan added.

Oliveira, responded at the meeting that the Massachusetts Bureau of Waste Site Cleanup does not require an assessment of the potential risk of explosion.

Explosion Fears

Fresh in the minds of many of the public commenters and questioners during the public meeting on the impact assessment were the 2018 Merrimack Valley explosions, which killed one, injured 20 and caused 80 fires, displacing 8,000 people.

The pressure in interstate pipelines such the Algonquin Pipeline system connected to the Weymouth compressor ranges from 200 to 1,500 pounds per square inch (psi). That pressure is more than in the pipelines that exploded in the Merrimack Valley, which were pressurized at 0.5 psi, Landrigan said.

Geologists have found that human-made land, such as where the compressor station was built, is not as stable because it sinks over time, said Brita Lundberg, chair of the board of Greater Boston Physicians for Social Responsibility. Enbridge also built the pipelines connected to the compressor station with the wrong material, which corrodes in contact with salt water. According to residents in the area, Enbridge is in the process of digging trenches to uncover gas pipes and install cathodes to protect them from corrosion.

The Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC), a county government agency based in Boston, also conducted a risk hazard assessment that did not consider the risk of fire or explosion. Marc Draisen, executive director of MAPC, has since backtracked on its risk assessment, acknowledging it was too superficial given the potential for explosion, malfunction or “serious mechanical or oversight failure,” though MAPC as an agency is not required to look into the impacts of potential explosions.

“MAPC wishes to reiterate its opposition to the natural gas compressor currently under construction in Weymouth,” according to the statement from Draisen, which also highlights MAPC’s lack of engagement with environmental justice communities in its assessment.

However, Enbridge spokesperson Max Bergeron said in a statement to NetZero Insider that “there are significant differences between interstate natural gas pipelines designed and certificated to safely operate at greater pressures.”

“Local natural gas distribution infrastructure, which may be designed with different materials, generally operates at lower pressures,” Bergeron said in the statement. The Merrimack Valley explosions involved “local natural gas distribution infrastructure, which is materially different from interstate natural gas infrastructure, including compressor station facilities.”

Arsenic Contamination

Spectra Energy, a natural gas transmission company that merged with Enbridge in 2017, said during a Weymouth Conservation Commission meeting in 2019 it found that arsenic levels in the coal ash are above state and federal standards.

Lundberg met with the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (DPH) about the arsenic contamination and the potential exacerbation of hazard risks with the natural gas facility before it was built. But the state agency has been largely absent in recent discussions about the contaminants and did not know the site had arsenic contamination until it was approached by the Greater Boston Physicians for Social Responsibility, Lundberg said.

DPH did not respond to requests for comment.

Shellfish in the water next to the compressor station are now known to be contaminated with arsenic, Lundberg said. But residents, particularly low-income or non-English speaking residents, still fish there because they do not know the water and the fish are full of toxins, as neither Enbridge nor the DPH have put up signs warning people.

The compressor station was built on a public easement, so members of the public can still walk near the property and have legal access to the water.

Resident Robert Kearns, who uses the park, said at the hearing that Algonquin is “not being a good neighbor” in refusing to post warning signs.

Kearns also said Algonquin should “clean up the beach as well as fulfill the promises that were made for the west waterfront to be a public park and not be calling us trespassers for using that area because that was a condition for the siting of the [Calpine] power plant.”

Oliveira apologized for describing users of the area as trespassers, acknowledging it was “maybe not the best use of the term.”

“What’s really needed here is a careful evaluation by an outside agency,” Landrigan said. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has grounds for being involved, Landrigan added, as the peninsula juts out into the Boston Harbor. Arsenic and asbestos could have leaked into that area as well, he said.

Next Steps

TRC said it will respond to comments on its assessment and provide any updates by Nov. 8. TRC’s “phase three remedial action plan” is due July 28, 2022.