The North Carolina Utilities Commission’s two-day technical conference on Duke Energy’s integrated resource plan (IRP), held Thursday and Friday, produced a flurry of industry jargon, the meaning of which varied depending on who was using it.

Duke’s “sequential peaker method” for determining when to retire specific coal plants in its 10,000 MW fleet was pitted against an “endogenous selection” approach recommended by clean energy advocates but labelled by Duke as being “single-source.”

Led by the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy (SACE) and the Carolinas Clean Energy Business Association (CCEBA), the advocates also pushed back on Duke’s plan to replace its coal-fired generation with significant new natural gas plants, calling instead for “all-source” procurements that could produce a portfolio of cheaper, cleaner alternatives. Duke argued that it already used competitive, “multisource procurements” based on the distinct system needs behind any one request for proposals (RFP) for new generation.

At the core of this war of words is Duke’s plan, as outlined in its September 2020 IRP, to keep 3,050 MW of its current coal fleet online at least through 2035 and add 9,600 MW of natural gas-fired generation. The technical conference was focused on the methodologies behind those figures and how they might be changed going forward.

Speaking for SACE, Rachel Wilson, principal associate for industry consultant Synapse Energy Economics, laid out the case for endogenous selection, in which the ordering and timing of coal retirements are determined by an advanced analytic platform, specifically the EnCompass modeling software.

“The first step in Duke’s methodology was to establish an order for unit retirements — rather than attempting to answer that key question … do the coal plants economically serve customer requirements — and then ranking them according to their value,” Wilson said. “Duke simply ordered the units according to capacity, with the smallest retiring first. So, the company’s economic analysis totally ignored the actual economics of these coal units.”

With endogenous selection, “the model’s decision is based on a calculation of unit profitability,” she said.

“For a unit that exists in an RTO like PJM, this is just the summation of its energy capacity and ancillary revenues minus its costs,” she said. “For Duke, which is operating in a vertically integrated area, this means a unit’s retirement is based on the cost of providing the next megawatt, whether that could be from an existing resource on the system, or it could be the cost to bring a new unit online.”

Duke executives at the technical conference defended the utility’s decarbonization strategy as balancing incremental emissions reductions with the need to maintain affordability and reliability. Downplaying energy storage as a not-yet-mature technology, they argued that Duke’s reliance on natural gas has allowed it to begin retiring coal while adding significant amounts of intermittent renewables, mostly solar. Since 2005, the utility has cut its carbon emissions per megawatt-hour of power generation from 1,025 pounds to 600 pounds today, according to figures in its IRP; it expects further reductions to 350 lbs/MWh by 2035.

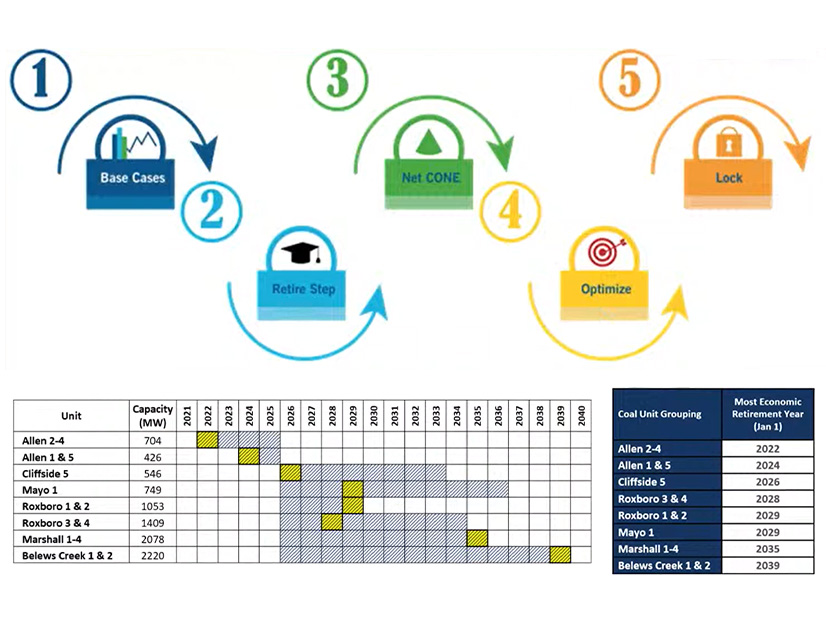

Mike Quinto, lead engineer on Duke Energy Carolinas’ resource planning and analytics team, similarly defended Duke’s “sequential peaker” methodology for determining coal plant retirements as encompassing both capacity expansion and production cost modeling that provides a more granular and transparent analysis than endogenous selection.

Using the sequential peaker approach, Duke first set the order of plant closures — which essentially came out from smallest to largest — and then used production cost computer modeling to determine the most economical date for retiring each facility, Quinto said. This approach “acknowledges that the retirement of one unit impacts the operations of the remaining units in the fleet,” he said. “So, as we retire one unit, it may require the rest of the fleet to respond in a different way.

Endogenous selection looks at plants independently, he said, which “would inaccurately represent the incremental costs that each unit has to the system, and further blur the lines of the true value to the system.”

“It removes chronology … how the system operates from one hour to the next or one week from the next, which is important for how renewables and how batteries operate and how the system responds to these,” Quinto said. “We lose some of that detail with these models. And finally, we lose the ability to dynamically forecast the costs of the existing units when determining that appropriate retirement date.”

South Carolina Plan Revised

Duke’s IRP is essentially a consolidated plan covering both Duke Energy Carolinas, which serves portions of both North and South Carolina, and Duke Energy Progress, North Carolina’s largest utility. When first released, Duke framed it as an advance in its planning process, noting it had developed six different scenarios for coal retirements and emissions reductions. Advocates in both states, however, quickly criticized the plan’s recommended base case, which kept more than 3,000 MW of coal online through 2035, along with the 9,600 MW of new natural gas.

The South Carolina Public Service Commission sent Duke back to the drawing board in June, with specific instructions on recalculating certain elements of the plan. For example, Duke’s modified South Carolina IRP, submitted in August, included additional scenarios that incorporated solar projects with single-axis tracking, which increases project output.

Duke’s new preferred plan retires all coal by 2035, also adding in 600 MW of onshore wind and 1,250 MW from energy efficiency and demand response initiatives, neither of which had been included in the original plan. Company executives at the NCUC technical conference also reported the utility would be using EnCompass as its modeling platform for its 2022 IRP, along with improved stakeholder engagement.

The NCUC has already held a number of public hearings on the original plan and collected thousands of pages of arguments from both sides, said Commissioner Dan Clodfelter, who chaired the Thursday and Friday sessions. But under state law, the commission can make comments on the plan but cannot order revisions, which to a certain extent refocused the debate more on Duke’s upcoming 2022 IRP, rather than further changes to the 2020 plan. (See Outspoken Public Pushes for Duke to Lead on Climate.)

Representing CCEBA, Steve Levitas, senior vice president at Pine Gate Renewables, a North Carolina developer, specifically called for any new all-source procurement to be implemented with Duke’s next IRP, rather than delay any upcoming renewable procurements.

“Absent new legislative direction, the commission should require immediate large-scale procurement in renewable energy,” he said.

The Colorado Experience

John Wilson, director of research at Resource Insight, Inc., criticized Duke’s approach to procurement as “single-source,” waiting until a coal plant is uneconomic to issue an RFP to replace it. With a technology neutral, all-source procurement, “you can provide the economic basis for scheduling those retirements much more effectively,” he said.

He pointed to Colorado’s experience with all-source procurements, which in 2016 allowed Xcel Colorado to retire two coal plants and replace them via an RFP that produced 417 bids. The resulting portfolio included wind, solar, storage and existing natural gas. Prices ranged from just over $0.01/kWh for wind, $0.023/kWh for solar and $0.03/kWh for storage, according to a presentation Xcel made earlier this year to the Michigan Public Service Commission.

Jeremy Fisher of Synapse discussed another 2018 all-source procurement by Northern Indiana Public Service Company (NIPSCO), which found that replacing existing coal plants with renewables provided more value and lower costs for the utility’s customers. To accurately compare costs, the RFP was done in advance of setting the order and timing of plant retirements, Fisher said.

“The first question they asked is, what’s the fundamental value of each of these [coal] units in 2023 and then, is there a better combination of retirements that happen in 2023 or 2028, and [offer] various opportunities to avoid impending capital requirements that would come through environmental obligations,” he said.

As a result, the utility targeted 2023 for retiring most of its coal fleet, keeping one plant online until 2028 and later moving up the retirement of two plants to 2021, Fisher said.

Commissioner Clodfelter also pressed the Duke executives on the issue. “As I hear it, you are defining need in a more discreet, ‘componentized’ way and looking at procurements relative to components or elements in that need,” he said. “And what I hear the other party’s advocating for is that we should define what they call total system need, and then you should seek procurement of a portfolio of resources that in the aggregate will satisfy that total system need.”

Asked about a 2018 RFP to replace peaking capacity, Jim Northrup, Duke’s director of economic analysis, said the 33 bids included natural gas, both combustion turbines and combined cycle, and hydropower. At the same time, under a state-mandated competitive procurement program for renewable energy, the utility has offered contracts for hundreds of megawatts of new solar in recent years, some of them to third-party developers.

Glen Snider, Duke’s head of long-term planning, said that fossil fuel retirements, new procurement and planning must take into account the evolution of technology and the grid.

“The system didn’t evolve overnight, and it’s not going to retire all of it overnight,” Snider said. “So, when you think about room for hydrogen or offshore wind, we really need to think beyond just retiring coal assets. By the time I get to the 2030s. I’m going to have a bunch of natural gas generators that went in in the late ‘90s and early 2000s that will be 35 years old. They are going to be approaching the end of their useful lives, and that will create additional need and room for new technologies to fill a future need that we’re really not talking about today.”