Members of the Herring Pond Wampanoag Tribe and the Penobscot Nation last week gave heartfelt explanations for why developers should not build transmission lines to bring Hydro-Québec’s power to New England, saying the utility’s projects have devastated tribal communities.

The hydroelectric power plants in Québec are “projects based on theft and destruction” that halted food supply to communities reliant on the land for hunting and rivers for fish, said Lokotah Sanborn, a Penobscot artist and advocate in Maine.

The severing of the rivers in Québec, the flooding of the forests and the tear of a transmission line through coastal pine barrens in Maine fragments the “spiritual and cultural ties to our homeland,” Melissa Ferretti, chair and president of the Herring Pond Wampanoag Tribe in Massachusetts, said during a webinar co-hosted by Maine Youth for Climate Justice (MYCJ) and the Sierra Club.

Maine residents will vote on a referendum in November that will determine the future of Hydro-Québec and Avangrid’s (NYSE:AGR) proposed New England Clean Energy Connect (NECEC), a $1.2 billion project that would include 145 miles of new transmission in the state. Approval of the ballot measure would put the project before the state legislature, requiring a two-thirds majority in both houses for the project to proceed.

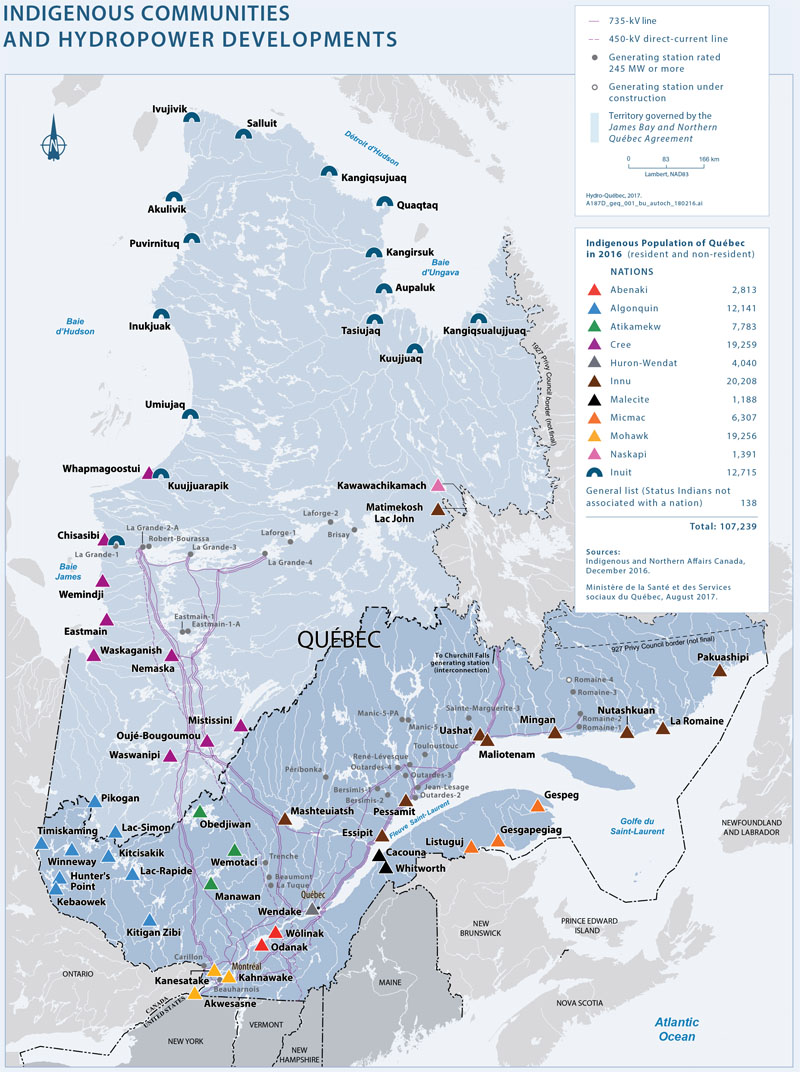

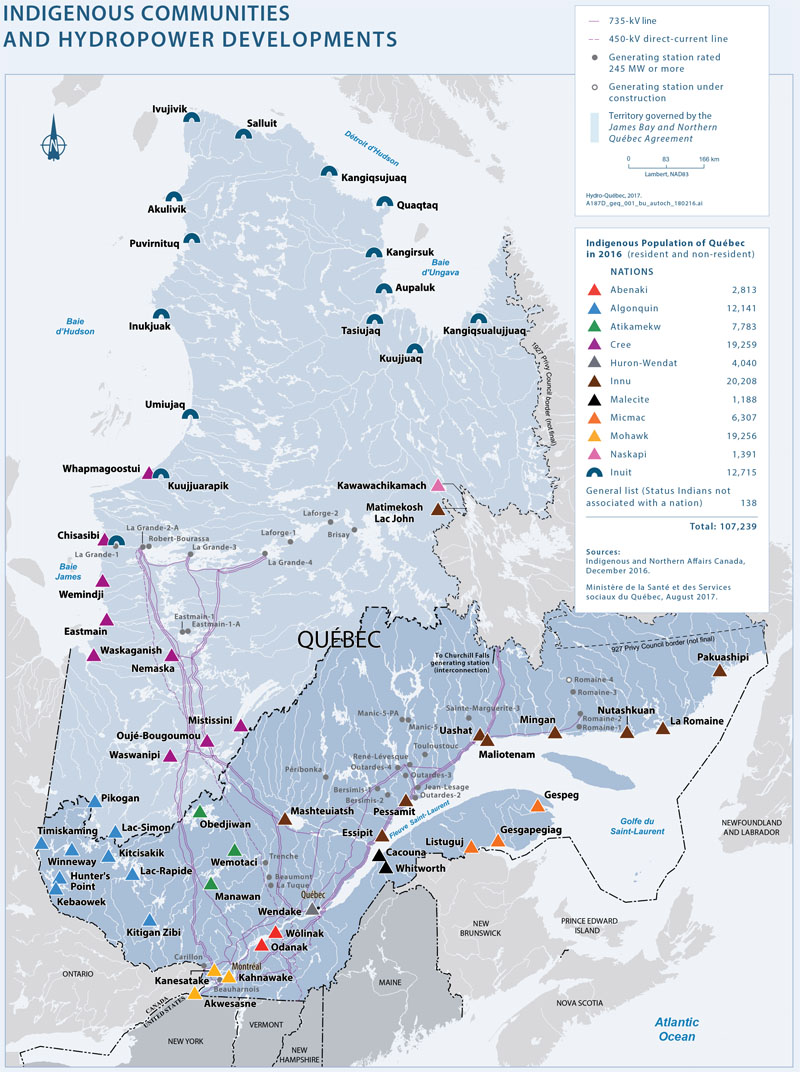

The project also faces potential litigation. A coalition of First Nations in Québec said in July it will file suit if necessary against the provincial government to stop construction of the NECEC line. The Lac Simon, Kitcisakik and Abitiwinni (Anishnabeg Nation), Wemotaci (Atilamekw Nation) and Pessamit (Innu Nation), representing about 7,000 people, claim that more than a third of the dam system providing electricity for the project is on lands the First Nations never ceded to the province.

‘Cultural Genocide’

Hydro-Québec represents half the hydro capacity in Canada and 60% of the country’s power. The company operates more than 60 hydropower generating stations and 28 reservoirs, with 550 dikes and dams across Québec. The utility has flooded 308 million acres of boreal forests since the 1970s to create reservoirs for its dams, according to Hydro-Québec spokesperson Lynn St. Laurent. The James Bay Project, in a region inhabited by Cree and Inuit north of Montreal, covers 68,000 square miles, an area larger than Florida.

Hydro-Québec says the James Bay and Northern Québec Agreement, signed by the governments of Québec and Canada, granted the Cree and Inuit Nations hunting, fishing and trapping rights in the territory, as well as financial compensation for certain services and mitigation measures. But tribes say hunting and fishing in these areas is no longer possible because the hydroelectric projects have shifted the migratory patterns for key game animals and make it difficult for fish to travel up the river to spawn.

Indigenous communities are losing their ability to maintain their culture, Ferretti said during the webinar.

“Indigenous communities are the most likely to be targeted by these energy projects,” she added, recalling the teachings she grew up with, of living off the land and cutting up freshly caught fish for dinner.

“Food in the store is too expensive,” Carlton Richards, a member of the Cree Nation, said in a video to MYCJ. He said the actions of Hydro-Québec and other hydroelectricity companies contribute to the “cultural genocide of Indigenous peoples.”

Lucien Wabanonik, a Lac Simon Anishnabe Nation councilor, wrote in a letter to the Sun Journal of Lewiston, Maine, that the agreements are “the product of coercion into forced agreements with minimal compensation.”

The Innu, whose Nitassinan homeland is the eastern portion of the Québec-Labrador Peninsula, say the water diversion from dikes and dams in the region flooded their hunting land and lowered the water levels of the rivers where they fish.

In July, Hydro-Québec signed an agreement creating a $57.6 million fund to be managed by the Innu of Ekuanitshit “to address Ekuanitshit’s preoccupations” regarding changes made to the Romaine hydro development project. The agreement includes the possibility of awarding direct contracts to Innu businesses related to the Romaine complex.

Last year, the Innu sued Hydro-Québec and Churchill Falls Corp. for $4 billion over the hydro project at Churchill Falls in central Labrador, the second largest hydroelectric underground power station in Canada, comprising 88 dikes and a 72,000-square-km reservoir. Hydro-Québec purchases more than 5,400 MW of Churchill Falls’ output.

A spokesperson for Hydro-Québec said that the company was limiting its comment on the matter while it is pending before the court. But the company insisted its projects “involve Indigenous representatives during the design stage of a project.” The company has a team of 150 environmental advisers from a “breadth of fields — biologists, anthropologists, sociologists, archeologists, geographers and more — along with 75 community relations advisers dedicated to improving our engagement across the province.”

“Our relationship with First Nations is not perfect,” the spokesperson said. “In certain areas it remains challenging, particularly where communities carry decades-old scars for a variety of reasons.”

New Projects?

In addition to NECEC, which would deliver Hydro-Québec’s power to New England, the utility also plans to send increased power to New York City through two transmission line projects selected last month, including the Champlain Hudson Power Express (CHPE). (See Two Transmission Projects Selected to Bring Low-carbon Power to NYC.)

Although Hydro-Québec says it will not need to build new dams and reservoirs to meet the increased demand from the U.S., “there is heavy concern that construction will begin on another proposed project known as Gull Island” in Labrador, Julian Felvinci, a member of the Maine Sierra Club Grassroots Network, said during the webinar. “That would be an even bigger dam [than Muskrat Falls in Newfoundland-Labrador] size-wise and capacity-wise,” at 232 km of reservoir area.

The North American Megadam Resistance Alliance cited a report conducted for it by NorthBridge Energy Partners that concluded Hydro-Québec’s export commitments would rise from 33.7 TWh to as much as 55.88 TWh as a result of its NECEC and CHPE commitments.

“Hydro-Québec [HQ] cannot meet the requirements for the NECEC and CHPE demand solely from existing generation facilities under the existing status quo conditions (including service of existing export volumes),” the report said. “The surplus generating capability and spillage cited by HQ and politicians as being capable of supporting these exports are highly variable and insufficient. Either HQ will have to back down existing export volumes, or build new hydro facilities, or resort to a combination of both strategies.”

A report by Energyzt Advisors for the Independent Power Producers of New York came to a similar conclusion. “Under average water conditions, the most likely scenario is that Hydro-Québec would simply divert energy from other exports into CHPE. Under dry conditions, Hydro-Québec would have to purchase energy from other markets to meet its contractual obligations,” it said.