ANN ARBOR, Mich. — Ann Arbor is considering creating Michigan’s first “sustainable energy utility” (SEU) — a nonprofit, publicly owned agency that would promote and help finance energy efficiency, renewable power and microgrids.

The proposal is outlined in a report released earlier this month by Ann Arbor’s Office of Sustainability and Innovations (OSI), which concluded that an SEU would be “more reliable, cheaper, cleaner, more local and more equitable than our current energy system and than a traditional municipal utility.”

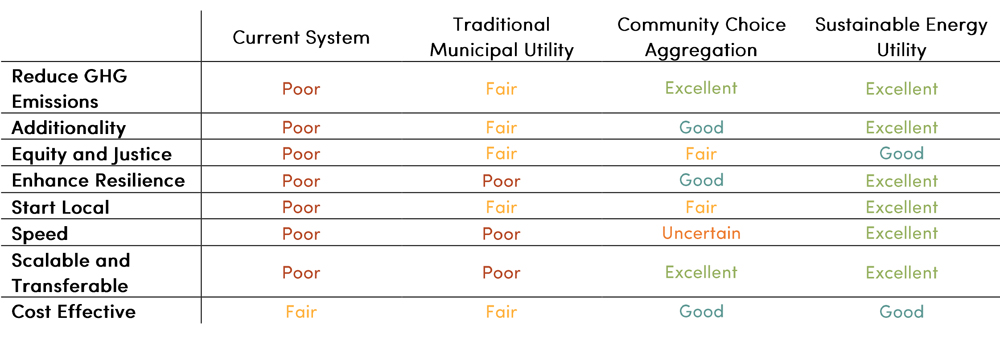

SEU vs. Municipal Utility, Community Choice Aggregation

An SEU has elements of a municipal utility, except that it would not own the poles, wires and other infrastructure. It also borrows elements of community choice aggregation (CCA).

Traditional municipal utilities own the electrical distribution infrastructure and sell electricity from third-party generators. Negotiations or court proceedings to determine the purchase price of an investor-owned utility’s assets can take years and cost millions, leaving the city with significant debt.

“A SEU is not about buying the IOU’s substations, circuits, poles and wires. It is not about investing in an outdated utility model with aging infrastructure,” the report said. “Instead, a SEU focuses investments in local energy generation (e.g., solar and geothermal), rigorous energy waste reduction measures, beneficial electrification and energy storage across a given geography (i.e., neighborhood, commercial corridor). The solar and energy storage systems could be installed for a single households or business, or, more ideally, be connected across each household or business through a series of microgrids.

“Over time, the SEU could grow to support additional initiatives such as district geothermal systems or other programs and initiatives desired by the community,” it added.

A sustainable energy utility — a nonprofit, publicly owned agency focused on providing locally sourced renewable power and microgrids to improve resiliency — has elements of a municipal utility and Community Choice Aggregation. | Ann Arbor Sustainable Energy Utility report

A sustainable energy utility — a nonprofit, publicly owned agency focused on providing locally sourced renewable power and microgrids to improve resiliency — has elements of a municipal utility and Community Choice Aggregation. | Ann Arbor Sustainable Energy Utility reportLike SEUs, CCAs do not purchase infrastructure. CCA customers can obtain renewable energy from a third party, paying the existing utility for delivering the power. But unlike SEUs, CCAs don’t have the authority to offer on-bill financing or other powers that are restricted to utilities. On-bill financing allows the cost of the improvements — such as more efficient windows and appliances — to be financed in part through energy savings and to stay with the home, as opposed to the resident. It can fund energy efficiency programs for underserved markets, such as rental housing.

An SEU can also offer financing with longer paybacks, overcoming an obstacle to more extensive retrofits.

Frustration with DTE

The city says the resilience offered by microgrids is central to an SEU’s appeal.

OSI Director Missy Stults said the release of the report was moved up in part because the city saw a number of power outages over the summer months during major storms.

“People are very frustrated with DTE” Energy (NYSE:DTE), the current utility, Ann Arbor City Councilmember Jen Eyer said. “The frequency with which we lose power is unacceptable.”

Asked to respond to the complaints, Brian Calka, director of renewable energy solutions at DTE, said, “DTE and the city of Ann Arbor have been partners with respect to clean energy for a number of years. We are working very extensively with their environmental sustainability office.”

“We continue to have significant dialogue with the city, and we definitely expect we will continue to engage with the city of Ann Arbor to help them achieve their particular carbon-neutrality goals by the end of this particular decade,” Calka said at a press conference DTE held with CMS Energy on community solar projects statewide.

Calka cited the Oct. 4 announcement of a new community solar project, to be built by the city and DTE. Stults said the project, which is expected to begin operations in 2023, may be part of an Ann Arbor SEU.

The city envisions the SEU as a “parallel” to DTE, allowing customers to use solar in the daytime, draw from batteries at night and use DTE’s electricity when local generation and storage can’t meet demand.

“When DTE has a power outage, SEU users still get power from the shared battery and solar systems,” the report said. “Over time, the system could become a closed microgrid loop that has limited to no connection to DTE’s grid.”

Local Generation Capacity

Creating an SEU would also help the city reach carbon-neutrality by 2030, a goal the City Council set in 2019 when it unanimously declared a climate emergency. That proposal called for the city to generate 78 MW through renewable sources on “viable buildings, parcels of land and carports.”

The city estimates rooftop solar could produce 400 MW, “one-third of total electricity consumption for residential, commercial and industrial users, along with the University of Michigan.” It cites Google’s Project Sunroof, which estimates that 71% of the roofs in the city, including residential and commercial buildings, are “solar viable” and that 60% of rooftops can support a system of over 5 kW.

Ann Arbor, a city of about 121,000, needs about 440 MW to meet its needs now, Stults said.

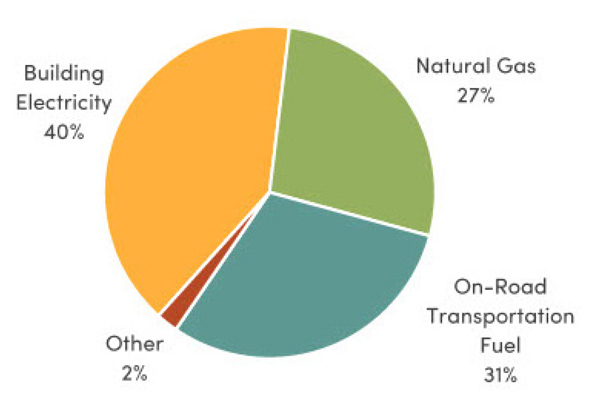

Community-wide greenhouse gas emissions by source | Ann Arbor Sustainable Energy Utility report

Community-wide greenhouse gas emissions by source | Ann Arbor Sustainable Energy Utility reportThe report contends an SEU could offer cheaper rates than DTE because “the SEU would not be concerned about profits to shareholders, maintaining aging assets, paying depreciation for the coal generation facilities that are being retired earlier than planned or upgrading large-scale distribution systems.

“The SEU would be laser-focused on generating energy from the cheapest sources available (energy waste reduction and renewables),” it added. “Our residents’ exposure to anticipated price escalations from fossil fuel generation feeding the grid would be greatly reduced — as would their vulnerability to larger and more prolonged grid outages that climate change is already bringing to Ann Arbor.”

The city said a community-wide rooftop solar installation program could reduce installation costs to $2/W, resulting in a levelized cost of energy of 5 cents/kWh, about one-third of DTE’s retail rate. “Bundling electrification and energy waste reduction upgrades with rooftop solar could reduce the incremental cost of electrification and generate cost savings,” it said.

Next Steps

There are still several steps to take before the city could begin SEU operations. The city’s Energy Commission is expected to propose to the City Council this fall that a feasibility study be done. Stults said residents will also be surveyed on their interest in alternatives to DTE.

There are only a few other SEUs in the U.S., and their focus is on energy efficiency more than generation.

The Delaware Sustainable Energy Utility and the D.C. Sustainable Energy Utility provide energy audits, rebates on new heating or cooling systems, programs for low-income households, and low interest loans and grants for solar and geothermal. “These SEUs operate in areas with more flexible legal frameworks than Michigan,” the report says.

Stults said that under Michigan law, a utility has to “sell power. And the only way to sell power [under Michigan law] is to generate power.”

Other SEU initiatives include the Sonoma County (Calif.) Efficiency Financing (SCEF) program, the California Statewide Communities Development Authority and the Pennsylvania Sustainable Energy Finance program.

Because Ann Arbor’s SEU would be the first in Michigan, the city acknowledges it “does not have a precise legal precedent.” But it said it can avoid challenges with the Michigan Legislature and use existing authority to begin work immediately.

Creating a CCA would require state legislation that the report says “would almost certainly face strong opposition from incumbent utilities” and could take years. In contrast, an SEU could be operating by the end of 2022, Stults said.

If CCA legislation is later enacted, the city could use it to procure renewable energy to fill demand not met by the SEU. “Thus, CCA and SEU are not competing strategies — but strategies that can be pursued simultaneously,” the report said.

How to raise startup financing for an SEU has not yet been considered. A referendum is expected in spring 2022 on Mayor Christopher Taylor’s proposed property tax increase to help pay for the city’s net-zero plan. Stults said the SEU could get some initial seed money from the millage, but under state law it would have to repay that because utilities must be self-sufficient.

Other sources for startup funding could include philanthropic donations or selling bonds, she said.